Ronaldo de Almeida

Clayton Guerreiro

In Matthew 18:20, Jesus said, “For where two or three gathered in my name, there am I am with them”. So, what to do when an agnostic and uninvited virus threatens to infect a group of believers, making them sick, or possibly dead?

In times of apocalyptic feelings, religious leaders worldwide are challenged to guide the believers and give meaning to the possibility of an approaching collective death (Elias, 2010). Specifically, in Brazil, religious groups are reacting quite differently. The Brazilian Spiritist Federation directed the Spiritist Centers to follow the Health Department’s recommendations and to continue activities online. The Afro-Brazilian groups do not answer to a specific leader, but several sources have informed that they are following social distancing in their places of worship, the terreiros.

Jewish synagogues and Islamic mosques have stressed the importance of sanitary isolation. Political leaders in both Israel and Palestine started an agreement, temporarily suspending historic conflicts. Political-religious wars are worth dying for, but not a newborn virus.

The Catholic Church’s official position, divulged by Pope Francis, recommended everyone to stay home. Some Catholic churches were open for prayer, but without agglomeration. In a famous scene, Pope Francis stood alone, under a light rain, and prayed in St. Peter’s Square granting forgiveness for all of those who lost their lives to the virus. This moment will forever be remembered in history.

The most controversial cases, nevertheless, have come from the evangelical[1] community, in which the reaction towards the theological-sanitary issue varies according to religious denominations, with distinct theological and political train of thought.

Generally speaking, historical Protestants (Baptists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Methodists, Lutherans and Anglicans) and Pentecostals have been following the sanitary guidelines to close the churches for religious services but keeping them open for prayers or individualized support. The online services exploded on digital media. For this evangelical community, the virtuality of the Internet does not seem an obstacle to the presence of Christ.

The solution found by such churches, like so many other people and groups, was to dedicate themselves almost exclusively to the virtual work. The volume of live-streaming has increased considerably and it includes homemade footage from pastors’ houses and broadcasts by professional teams inside churches. The latter includes the presence of a few pastors, musicians, and singers, but no believers.

The use of technological media by Brazilian evangelicals is not exactly a novelty (Cunha, 2007). Their presence on radio and television is longstanding, and the dimension of virtuality has been explored by them for a long time on the internet. However, these virtual practices have been intensified and diversified. In some cases, they have adapted evangelical doctrines. In online services, for instance, these groups started doing the administration of sacraments or ordinances by virtual media, such as the holy supper (Eucharist) and baptism. On social media, many people posted several pictures of tables from their houses with grape juices and pieces of bread for their Holy Supper.

The online baptisms were carried out via large video screens, with the pastor pouring water from the baptismal tank and the believers baptizing themselves in their homes. This practice was met with controversy. As a joke, evangelical critics have called this ritual “baptism by invention” or “baptism by transmission”, as an allusion to “baptism by immersion”, “baptism by affusion (pouring)” and “baptism by aspersion (sprinkling)”.

Indeed, the sacraments/ordinances intend to produce individual transformation, by the consequent integration of the person in the believers’ community (in the case of the rite of passage of baptism), and the confirmation of the individual in the Christian community. It happens through collective memory and the divine presence production, and might be done physically, spiritually, or symbolically.

Therefore, the aforementioned practices and media (cell phones, TV, large video screens) indicate both an attempt to produce a sense of community, in times of social distancing, and a way of producing the divine presence to ratify community belonging. Doing so, these practices find a way to supplant a physical place of worship. At this point, is important to stress that Christian cosmology does not attribute a body to the Holy Spirit, but the believer’s body is the Holy Spirit temple itself. In short, even if the believer cannot go to the church to feel the divine presence, it is possible to feel it in his body, since the church goes to him through different media (Meyer, 2011).

Beyond rituals adaptions, the closing of the churches generated a strong controversy among politicians and religious leaders. Some Pentecostal pastors disagreed about the social isolation and resisted closing their churches. Pastor Silas Malafaia, Bishop Macedo, Bishop R.R. Soares, Apostle Valdemiro Santiago[2], and other lesser-known leaders, have echoed the messages of the President of Brazil, Jair Messias Bolsonaro. While many State Governors and City Mayors decreed that only essential services, such as hospitals, supermarkets, pharmacies, and gas stations, could be maintained, Bolsonaro and his main evangelical allies claimed that the religious temples should stay open.

Faced with the complaint of the main Brazilian Pentecostal leaders about the closing of the churches, the Brazilian President decreed religious activities as essential services. They argued that religion would offer fundamental psychological support to people who would be disoriented by the fear caused by the new coronavirus. When the pandemic started, many pastors promised to cure Covid-19 by using consecrated religious objects and financial offerings. This assertion has gradually been replaced by the argument that the churches would be “hospitals” to help the “desperate” people. According to the pastor and psychologist Silas Malafaia, one of Bolsonaro’s most enthusiastic supporters, “faith” and “optimism” would be “fundamental elements for immune defenses”.

This position derives, in part, from the political situation surrounding the pandemic. The protagonist here is the president of Brazil, who is standing against the recommendations of WHO (World Health Organization) and almost all world leaders. He has repeated several of Donald Trump’s steps in the United States: Science Denial; minimizing the effects of the disease; proposing vertical isolation[3]; use of drugs that have not been scientifically proven yet, such as hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine; immunization of the population through the spread of the virus, which implies countless deaths; nomination of Covid-19 as a “Chinese virus”. However, by not following the American president’s partial retreat, Bolsonaro was considered the worst world leader in fighting the pandemic and his position was compared to the presidents of Nicaragua, Belarus, and Turkmenistan.

In Brazil, President Bolsonaro has successfully brought together evangelicals around him (Almeida, 2019). Many positions in the Bolsonaro administration are held by religious persons, including six Ministers of State (three ministers are pastors). Besides the militaries, conservative evangelicals form one of the main bases for electoral, parliamentary, and cadres support for federal administration positions. Although “bolsonarism” has been losing support among some ex-allies (governors, mayors, parliamentarians, businessmen, and voters) who disagreed with the denial of the pandemic, the main Pentecostal leaders continue to support Bolsonaro.

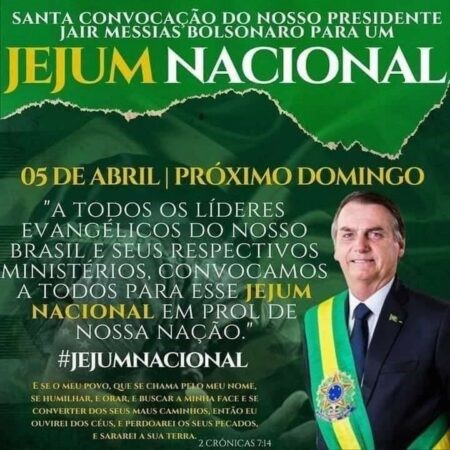

This entanglement was seen in the “holy convocation” of a national fasting by Bolsonaro, as a strategy to combat the new coronavirus. Although fasting is a common practice for several religions in Brazil, it is important to note that the promotional video included thirty-two religious leaders, mostly representatives of Pentecostal, Baptist, and Presbyterian denominations. There were no religious leaders from Catholic, Jewish, Islamic, or Afro-Brazilian denominations present in the advertising piece. Quite a few evangelical leaders – Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists, Congregational, and Pentecostals mostly – criticized the movement as political and religious manipulation by the President.

In the height of Corona, when doctors and scientists recommend eating regular to boost immunity, religious leaders have prescribed fasting and prayer, as a method for overcoming fear and maintaining hope. While the churches have been closed, believers have spread themselves throughout Brazil, including the residence of the Presidency of the Republic, Palácio da Alvorada. Some worshippers clothed themselves in the colors of our national flag, green, yellow, blue, and white, raising their hands over the city and kneeling on the flags of Brazil and Israel. Other believers and religious leaders marched around the churches and uttered several prophetic words, arguing that “Jesus Christ is the Lord of Brazil,” and that no “plague would reach the national tent”. In other words, there would be a special divine plan for Brazil, as if fasting could immunize the nation against the global pandemic.

Despite religious leaders’ wide support for fasting and different measures for approaching the health crisis, they did not receive the support from believers in the same proportion. Even though several believers have adhered to fasting, the vast majority stayed in their homes.

One of the fallacies emphasized by religious leaders and politicians can be identified in the field of law. They have stressed that believers should choose between God’s law and human’s law. If divine law indicates the importance of collective meetings for the sacraments and regular services, it also supports the need to obey the authorities, as they preach from Romans 13: 1: “Everyone must submit himself to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which is from God. The authorities that exist have been appointed by God”. Following these ideas, the “bolsonarists’” argument is that the authority who should be obeyed is the president, disregarding the state, municipality, and Ministry of Health guidelines in that moment.[4]

In Brazil, we also can identify a rhetoric of a persecution complex, widely disseminated in churches, in which pastors have emphasized a supposed plan by the State, the media, other religions (overall muslins), and an imaginary communism that persecutes evangelical churches. During the pandemic, this thinking was brought up again, with the argument that the churches were being pursued by governors and mayors. They considered that closing the churches would undermine the right to Freedom of Religion guaranteed by the Brazilian Constitution.

Thereby, there is the idea that an individual right (Freedom of Religion) could override social interests (collective health), disregarding the exceptionality of the moment and the fact that the Brazilian Constitution itself guarantees the well-being of all citizens, religious or not.

One of the great ironies in the social process described above is that the religious agents who mainly employ the internet, television, and radio to propagate their beliefs (Campos, 2008) have been the most bothered with the temporary closure of religious activities in the temples in Brazil. We would like to recall that Christian doctrine emphasizes the possibility of ritual practice in environments other than the sanctuary itself. Therefore, since evangelicals argue that the body is the temple of the Holy Spirit, why would it be necessary to meet in a physical location?

Like many businesspeople, the main Pentecostal leaders echoed the president’s discourse that instead of social isolation, vertical isolation would be ideal because it would allow people outside the risk group to go back to normal life. During the day, at work; at night, they could go to their respective religious worshiping places. According to these leaders, this position would not cause harm to the economy, which has performed weakly even before the pandemic, in the first year of Bolsonaro’s government. However, vertical isolation has been criticized by the majority of the press and by most scientists.

The similarity among these discourses generated distrust and raised questions. How could the pastors collect offerings and tithes if the churches were closed? How could they maintain the professional structures of certain denominations, with hundreds of employees and monthly maintenance expenses? How could they maintain church-owned TV channels or pay rent for church buildings in strategic areas of Brazilian cities?

One of the possibilities would be their connections with the federal government. In this sense, the news recently reported that there would negotiations between the government and evangelical churches regarding the forgiveness of tax debt of millions of reais, the official currency of Brazil.[5]

Other solutions to the alleged financial insolvency would be online collections, bank transfers, and donations via credit cards. In addition, some pastors have offered religious services inspired by drive-in movies, with the believers in their cars, while the church workers would circulate among them in order to collect financial contributions. Meanwhile, the revenues decreased when compared to those earned during regular church services, indicating that the closing of the churches had impacted the financial contributions.

In conclusion, we would like to emphasize the scope of the pandemic and the effects of the resulting need for social distancing. This required the pastors to deepen their tactics, already established for maintaining the religious machine even without the believers’ physical presence in the churches. During the pandemic, many evangelicals have withdrawn their support of the government because of the bad management of the health crisis. However, at the same time the proximity of the main actors of Brazilian Pentecostals to Bolsonaro seemed to consolidate the idea that these religious groups are a solid support base for “bolsonarism”, alongside Baptist and Presbyterian fundamentalist pastors. Among official statements, live-streaming, and public appearances, the religious and political discourses evidenced alignment in several aspects: denial of the pandemic, attempts to keep the churches open, the allusion to the Freedom of Religion, the persecution complex, and the concern about the economy.

With the closing of the churches, the evangelical groups needed to adapt ritual practices as a way of producing community belonging. Although the believer’s body can be considered the temple of God, the pandemic seemed to indicate the centrality of physical temples for Pentecostal religious practices in Brazil.

Ronaldo de Almeida is Professor at the Anthropology Department at the University of Campinas, and researcher at Cebrap, Brazil. He is the author of A Igreja Universal e seus demônios: Um Estudo Etnográfico (2009, Terceiro Nome), yet to be translated into English.

Clayton Guerreiro is visiting researcher in the Religious Matters Project, Utrecht University, PhD Student in Social Sciences at the University of Campinas, and researcher at Cebrap, Brazil.

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.

References

ALMEIDA, Ronaldo de. Bolsonaro presidente: conservadorismo, evangelismo e a crise brasileira.Novos estudos CEBRAP [online]. 2019, vol.38, n.1, p.185-213, 2019.

CAMPOS, Leonildo Silveira. Evangélicos e Mídia no Brasil – Uma História de Acertos e Desacertos. Revista de Estudos da Religião, p. 1-26, setembro 2008.

CUNHA, Magali do Nascimento. A explosão gospel:Um olhar das ciências humanas sobre o cenário evangélico no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2007.

ELIAS, Norbert. The Loneliness of the Dying and Humana Condition. Edited by Alan Scott and Brigitte Scott. Chester Springs PA: University College Dublin Press/Dufour Editions, 2010.

MEYER, Birgit. Mediation and immediacy: sensational forms, semiotic ideologies and the question of the medium. Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale, 19, 1 23–39, 2011.

Notes

[1] In Brazil, the term evangelical is used to designate different Protestants and Pentecostals branches.

[2] Respectively, they are leaders to the following denominations: Assembly of God Victory in Christ, Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, International Church of the Grace of God, and World Church of the Power of God.

[3] It consists only of the social isolation of risk groups people, namely the elderly and those who have a pre-existing disease.

[4] During the pandemic, two Ministers of Health, who are also doctors, resigned because they disagreed with Bolsonaro in conducting the health crisis. Nowadays, Brazil has a General of the Army as a provisional Minister of Health.