Wytze J. Dijkstra

In her recently premiered theater performance “My Religion Doesn’t Define Me” (2022), Afra Ernst, artist name Rumah Afra, engages her audience in the hardship she experiences with manifesting her religious identity in Dutch society. The performance is both a conceptual and a corporeal reflection on the equivocal place of Islamic identity in Dutch society that Ernst experiences: “For a long time, I’ve experienced my religion as a burden to the outside world. Until recently, I did not tell many people that I am Islamic because I was afraid they would judge me for that,”[1] says Ernst. Taking ‘judgement’, and the stigmatization and framing that comes with judgement as the central themes to the performance, Ernst tries to invite her audience to participate in the story she tells: through these relational themes the performers and partakers to the performance are entangled. Together with dancing partner Senna Amarnis, Afra Ernst attempts to engage in dialogue about multiple belongings and essentialist views on Islamic identity, while simultaneously questioning the frames of reference of that very dialogue.[2] Working with nothing but lines of sand as dancing tool, Ernst’s performance alerts us to a compelling material dimension of religion: the movement and aesthetics of the dancing human body. After I had been to the performance, I got passionate to write about it. I think that “My Religion Doesn’t Define Me” offers a provocative and timely perspective on material and aesthetic approaches to religion, and raises interesting possibilities of cross-disciplinary dialogue between artists and academics.

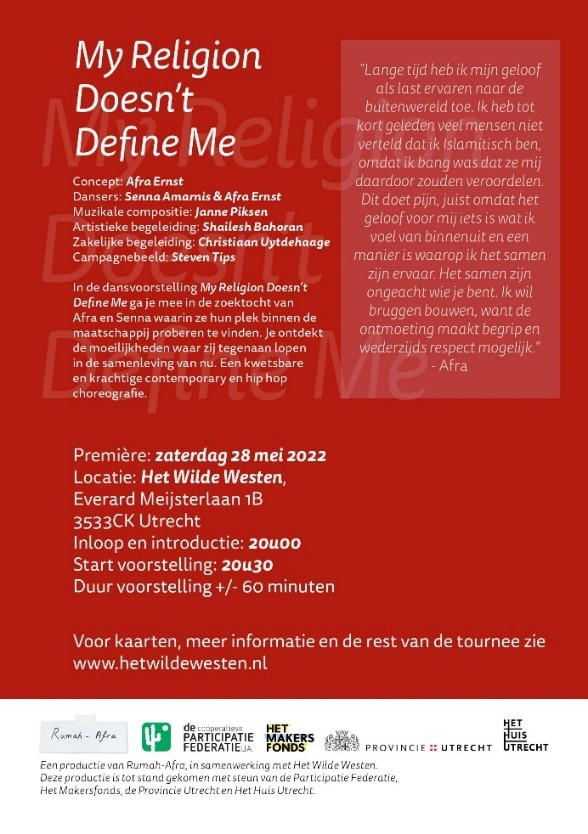

Poster for “My Religion Doesn’t Define Me”. Left: Senna Amarnis, right: Afra Ernst. © Steven Tips

Dancing discontent

The stage onto which Ernst and Amarnis appear is empty, except for the outlines of a small square frame, made of sand. With the sound of a female voice speaking in Indonesian, and that of a man speaking in Arabic filling the room, the lights turn on, the two dancers appear, and start moving. As the voices continue to alternate in speech, Ernst and Amarnis begin to perform an intricate contemporary hip-hop choreography. Their repeated and introspective movements evoke an idea of prostration and devotion, as if they were performing a prayer ritual. Ernst and Amarnis repeat their movements time after time, and they engage the audience in an interaction between an internal, contemplative process and its external, material presence. This space of stretch and repetition, marked by the subtle nuances in the way in which the dance develops, invites the audience to reflect, on the relation between the voices of the two people talking and the two dancers, and on the meaning of the square frame to which the dancers relate. Ernst and Amarnis’ restricted movement on the empty stage allows for the audience to actively think with the performers – to think about how they experience the frame they’re caught up in, who constructed it, and about what might be a ‘way out’.

Gradually, the intensity of the dance grows, from a peaceful and uninhibited pace, to a troubled and voluminous performance. An apparent struggle that Ernst and Amarnis experience is amplified by their wilder and staccato growing body movements, suggesting a resistance they find in themselves. Whereas at first the square frame could have been a safe demarcated place for the dancers, it now becomes clear that the frame is a constraining factor. The developments and nuances in their bodily movements bring into presence a discontent, a discontent that they continue to communicate through the movements with which they began their performance. Ernst and Amarnis start engaging with the lines of the square more and more; they flirt with the square’s edges and move about it forcefully and determinate. Throughout the room, the anticipation raises for the moment when Ernst and Amarnis will step over the line of sand, when they escape the grid that holds them captive, and when they break out.

But they do not answer to that anticipation in any straightforward way. Instead of stepping over the dividing lines of sand, Ernst and Amarnis step onto the lines of their frame. Silence fills the room, and nothing except the crackling sound of feet and toes finding their way on the sand is heard. It is a turn in the performance and a moment of tension release, but in a place where one would perhaps not have seen it coming. I realized that the dancers stepping onto the dividing line of in and out posed a challenge to my own scripts of thought, my own frames of reference. For me, the straight lines of the square frame symbolized the border between an inside and an outside, and the inevitable and scripted outcome of the performance, for me, would be for the dancers to break free from their restraining frames, and to find a ‘way out’. As the performance unfolded, I became aware of the fact that I was narrating ahead as the performance took place, and that this narration was based on my preconceived notions of how lines, boxes, and frames function.

Instead of stepping over the line and acknowledging the straight line’s currency, Ernst and Amarnis dance on the line and use the line. They bend and curl the line to fit their movements, and to fit themselves relationally to the sand. Doing so, the straight lines of the square frame curl into a beautiful work of art. As soon as they engage with the lines on those very lines, any idea of direction also disappears. With sand moving in every direction, there is no telling of what is brought in and what is pushed out. Moreover, any straightforward judgment of that movement appears arbitrary in light of the complex audiovisual field unfolding.

In the end, the sand remains, baring no traces of the frame in which the dancers previously found themselves, but nevertheless made up out of the very same material. After 45 minutes of dance, Ernst and Amarnis get up and, in silence, contemplate the sandscape they made. Their backs are facing the audience, and with the lights in the room turning on again, as the end to the performance, they amplify their roles as partakers.

Curling straight lines

I read Ernst’s curling of the sand as a challenge to a certain aesthetic, an aesthetic of straight lines. The meaning of shape and the extent to which shape is considered fixed, is rooted in epistemes of knowledge that cater to a very particular line of thinking (Van de Port 2016, 167-168), and shapes can serve as applicators of power in ways that disciplines human subjectivity (Hazard 2013, 61). Shape both enables and constrains. With challenging the presumed fixity of shape, Ernst does not challenge any particular stigma or stereotype, but she challenges the principles of the frame on which stigmatization itself is based. Curling straight lines, she opens the door to discussion on multiple belongings and the complex and ambiguous nature of identification. She stretches and bends the meaning of both the line and the frame, and what it means to be ‘in’ or ‘out’. The openness of the curls complicates any straightforward comprehension that a binary of in vs out, structured around lines, provide (Law 2016). Instead of overcoming a binary altogether, Ernst plays and works with the binary of in vs out, acknowledging it, disrupting it, and making ambiguous for the onlooker as to what exactly any emancipation as opposed to her frame would look like.

Taking judgement, stigmatization and framing as central themes to the performance, Afra Ernst addresses the audience in the room. With the use of dance and sand, Ernst materializes stigmatization and judgement. The inherent mechanisms of dependency and ambiguity in stigmatization and judgement (Goffman 1990 (1963), 9), mechanisms that Ernst visualizes in dancing with sand, provide an entangled space in which an instructive dialogue can be held. Frames don’t transpire in isolation, but are always socially and relationally produced. Ernst: “The frame does not just belong to me, it belongs to the audience as well.”[3] The square frame on stage is not just Ernst’s or Amarnis’ – whoever it is in the audience, in one way or another knows the frame, dominates with the frame, is dominated by the frame, engages with the frame: “Stepping onto that dividing line, I address those judging or framing me, but at the same time I also address myself. It takes courage to come out and complicate the image that others have of you,”[4] says Ernst.

Ernst’s performance pointed me to the possible gains from cross-disciplinary dialogue between artists and academics. The challenge Ernst poses to binary ideas about belonging and identity, about being ‘in’ or being ‘out’ through an aesthetics of curls, directs attention towards the different media that people mobilize to communicate their ideas and arguments. Specifically, Ernst’s performance directs our gaze towards the distortion that the medium of writing on lived religion and multiculturalism can entail; a distortion of lived, complex reality into clarity and straightness. It raises the question of how, in our methodological considerations and approaches, we can do more justice to the complex, messy, ambiguous and contradictory nature of multicultural and multireligious belonging? One way, for me, would be to pay close attention to what artists like Afra Ernst do. Artistic engagement with societal issues such as Ernst’s performance is channeled first and foremost through a deep acknowledgment of positionality, personal stakes, and urgency (Nachmanovitch 1990, 22-23). For academics theorizing about lived social reality, artists and performers like Afra might provide an extremely valuable entry point into lived realities and lived religion.

Wytze J. Dijkstra is currently a Religious Studies Research Master’s student at Utrecht University. He completed his undergraduate degree in Islamic and Arabic Studies. His main research areas are the entanglement of Jewish and Arabic identities in Palestine and Israel, Post-Zionism, and contemporary Jewish history in Egypt. In his Master thesis, he explores the timely heritagization of Judaism in Egypt.

References

[1] Interview with Afra Ernst on “My Religion Doesn’t Define Me”, 2022.

[2] For more information on the performance dates and practicalities, see https://www.hetwildewesten.nl/

[3] Interview with Afra Ernst on “My Religion Doesn’t Define Me”, 2022.

[4] Interview with Afra Ernst on “My Religion Doesn’t Define Me”, 2022.

Bibliography

Goffman, Erving. 1990 (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin Books.

Hazard, Sonia. 2013. “The Material Turn in the Study of Religion.” Religion and Society: Advances in Research 4: 58-78.

Law, John. 2016. “Modes of Knowing: Resources from the Baroque.” In Modes of Knowing: Resources from the Baroque, edited by John Law and Evelyn Ruppert, 17-58. Manchester: Mattering Press.

Nachmanovitch, Stephen. 1990. Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art. New York: Penguin Putnam.

Port, Mattijs van de. 2016. “Baroque as Tension: Introducing Turmoil and Turbulence in the Academic Text.” In Modes of Knowing: Resources from the Baroque, edited by John Law and Evelyn Ruppert, 165-196. Manchester: Mattering Press.