Neha Khetrapal & Samah Nanda

A chain of vicissitudes unleashed by Covid-19 meant that devout people turned to benevolent deities. Paradoxically, the world witnessed images of ‘Goddesses’ that were ostensibly fiery, hot-tempered or appeared controlling.

Via Sandhya Kumari/Gallerist.in/CC BY-SA

Would devotees not like to take solace from their belief in a benevolent God in order to brave these exceptional times? Or, do they imbue their world, including their religious or ritualistic practices and God, with hostile overtones consistent with the harsh living conditions?

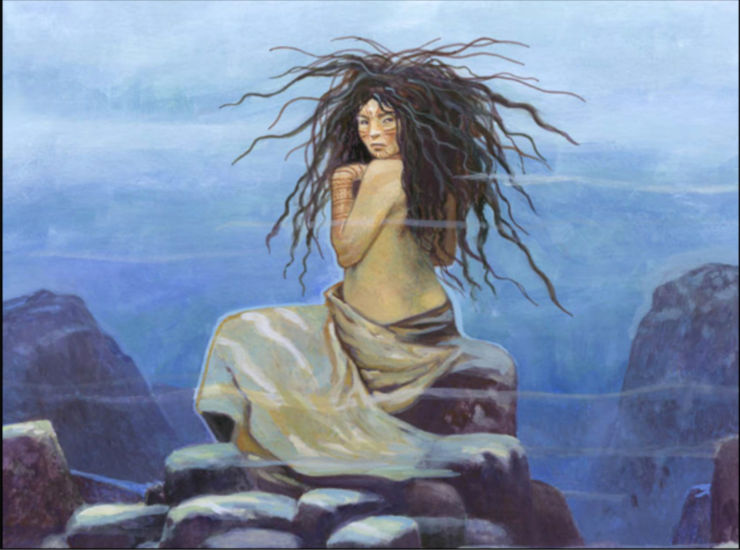

Human history is replete with examples of controlling, punitive and vengeful deities that have emerged across different time spans in line with the turbulent changes. The Netsilik Inuit from Central Canada, inhabiting the harsh Arctic environment, believed in Sedna or the Goddess of the sea and marine animals. Sedna is a vengeful deity (see Image 2) who must be appeased by conducting certain rituals.

For instance, sharing meat with other members of the community. And individuals who deviated from the established social norms were believed to be punished (e.g., Falkner, 2020). The beliefs and the associated rituals helped sustain cooperation among the Netsilik Inuit.

Travelling to the east, a demon-turned Goddess, named Hariti (see Image 3), is worshipped by Indians as the protector of children.

Via Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh – Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh CC BY-SA 4.0

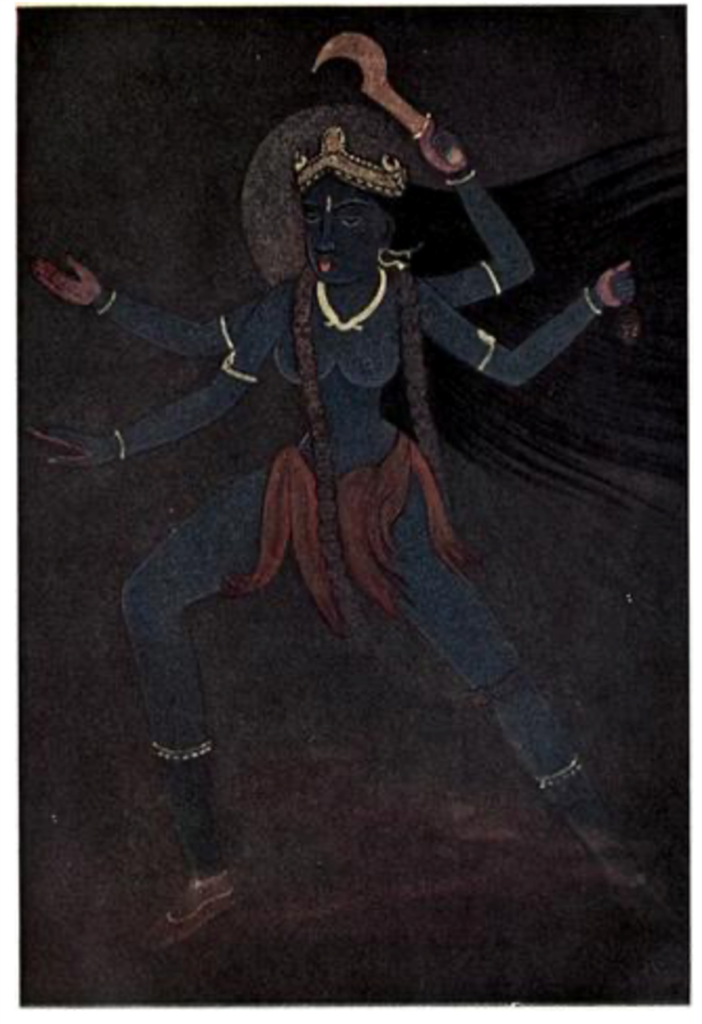

Few scholars trace her as the smallpox Goddess (e.g. Padma, 2011). Kali (see Image 4), another fierce Goddess, gained prominence in the Eastern part of India after the great famine of 1772.

More recently, ‘Pilague-amma’ found abode in one of the southern states of India during the plague of 1994 (Srinivas, 2020). In the contemporary world, widespread uncertainty associated with Covid-19 was responsible for the birth of ‘Corona Mai’ or Coronavirus Goddess [see Image 5].

(source).

People in parts of India were seen worshipping the Goddess and performing rituals to appease her (Khetrapal, 2020).

The Benevolent or the Interventionist or Controlling/Harsh Deity

Research from psychology informs readers that believing in a loving and a benevolent God promotes mental wellbeing (Bradshaw, Ellison, & Marcum, 2010). Why do devotees reconstruct fiery, controlling or punitive deities just when they may need a loving one? McNamara & Purzycki (2020) claim that believing in Gods that are harsh, controlling and punitive lays the foundation for cooperation at the group level. Such beliefs deter people from following self-vested individual interests and translates into tangible benefits for maintaining the larger group in the midst of a crisis where ‘social cooperation and cohesion’ could be the key to survival.

Fearing punishment for defection from an all encompassing and a watchful eye-in-the-sky may have, thus, worked to increase human survival in the past, especially, where cooperation has been the key for orchestrating a collective response to threats of ecological stressors. But, does the current threat posed by the Coronavirus match the threats that people faced in the past (e.g. invasions or other natural disasters)? Many readers may agree that the threats are comparable and group solidarity may again play a key role in braving the challenges that are associated with the prevailing circumstances. Hence, the appearance of ‘Godly’ fiery images is consistent with the prior explanations advanced by McNamara & Purzycki (2020). We attempt to integrate the ‘group solidarity’ explanation with the ‘religious struggles’ that became apparent during Covid-19.

Although religious struggles can take on different forms, chief among them are feelings of abandonment by God or hostility towards God. Currently, there is lack of data on religious struggles for the current pandemic. But a few preliminary studies discuss the nature of moral struggles experienced by frontline workers (Doehring, 2020). In comparison, the general public might be struggling to accommodate a benevolent image of their God within the broader array of adversities triggered by the pandemic (Dein et al., 2020). A long-term consequence of this struggle could lead to mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression. Supporting evidence comes from a recent study by Lee (2020) who reported relations between higher levels of struggle with God and elevated scores on a Coronavirus Anxiety Scale.

Religious Struggles, Mental Wellbeing and Deities

Believing in one omnipotent God creates emotional burden for devotees, particularly, during personally stressful times (Beck and Taylor, 2008). The ensuing emotional burden poses a challenge for mental wellbeing. Beck and Taylor (2008) propose that the emotional burden could be attenuated by a belief in Satan under the monotheistic umbrella. We build on the proposal in offering an explanation for the appearance of ‘Godly’ fiery images during the pandemic. In this attempt, we impart importance to the concept of polytheism.

The concept of polytheism entails a belief that there is more than one deity and involves the worship of multiple divinities. The polytheistic traditions are known for distinctive characteristics. Chief among these is a belief that each divinity is associated with a specific function (e.g. healing), or is in the possession of a specific power. It’s not uncommon to come across Gods for rain or other seasons under the polytheistic tradition. A divine division of power finds parallels within our modern democratic society, i.e. bureaucracy. Hinduism is a prime example wherein various Gods are honoured and worshipped. Examples include Surya (the Sun God), Ganesh (Lord of Success), and Lakshmi (Goddess of Wealth) [see Image 6].

In line with the arguments developed so far, believing in a benevolent God is advantageous and has important implications for mental wellbeing (Stroope, Draper, & Whitehead, 2013). However, attributing both disaster and prosperity to one God (under the monotheistic tradition) or a few major Gods (under the polytheistic traditions) creates theological and emotional tensions. In order to counteract the impact of harsh living conditions (e.g. parasitic stress) and the consequent religious struggles with an omnipotent God, devotees may turn to a punitive, controlling or harsh God. Under the polytheistic traditions, interventionist characteristics of a secondary God are translated into ‘fiery’ images or deities.

Our explanations invite another speculation: Could we draw a direct link between the increasing appearance of deities (e.g. Hariti or Pilague-amma) and stressors or threats? Could this link be used to explain the reductions of incarnations with improved infrastructure and medical facilities, except for ‘Corona Mai’ who dominated the world of a few devotees. Noteworthy, the world did not witness an ecological threat as large as the pandemic in decades.

Our speculation gets us to another closely connected question: What happens to the status of the deities after the threat subsides? First, the Gods may lose their revered places once the turbulent or stressful times die down. Oladevi is one such example. People from one of the Eastern states of India (West Bengal) worship Oladevi [see Image 7] in the hope that the Goddess will save the worshippers from diseases like cholera, jaundice, and diarrhoea. The Goddess emerged when the Indian subcontinent was in the grips of cholera during the 19th century CE.

The significance of the Goddess declined in line with the control of cholera with improvements in medical science and sanitation. Second, the interventionist and controlling Gods could be viewed as gentle with the passage of time. Goddess Kali serves as an example here. In her earliest appearances, the Goddess is depicted as skeletal and frightening with black skin (literal interpretation of her name). Later, the image of Kali underwent a make-over and she was depicted as motherly with a gentle smile, wearing ornaments with a blue complexion [see the changing imagery of Kali below].

In a nutshell, our explanation for the rise of punitive and fiery images of God rests on the conjecture that polytheistic traditions play an important role. A strong belief in only one God could lead to the decline in its status as a protector when calamity strikes. We have already seen this to be the case during the Black Death of 1347-1352 CE [see Image 10].

The perceived failure of God to answer people’s prayers contributed to the decline of the Church’s power in Europe. It is a matter of speculation and research whether and when devotees would turn to other supernatural powers (e.g. witchcraft) as a means of dealing with their theological tension under the polytheistic tradition.

Polytheistic Traditions and Compensatory Control

Confronting a chaotic world provokes anxiety (van den Bos & Lind, 2002) and serves as a potent motivator for people to search for external sources of control. A successful search for a source of control relieves anxiety. Tight links between psychological wellbeing and a reliance on an external source of control, such as an interventionist God was proposed nearly a decade ago (Kay et al., 2010). Since then, the proposal has earned support from a variety of studies in psychology and the social sciences. We build on the explanation and further propose that a polytheistic milieu precipitates beliefs in a novel interventionist deity and ignites concomitant rituals as proxies for psychological coping. In support of our proposal, we underscore archival evidence that casted light on increased interest in strictly controlling religious doctrines in the wake of economic depressions (Sales, 1972).

In line with our explanation, a focus on a new deity not only serves as a psychological medium for guarding against a chaotic world but also serves to maintain the influence of known benevolent Gods who have been worshipped by generations. To reiterate, the focus on a controlling deity slides gradually as anxiety-provoking events ease out. The attenuated popularity of Oladevi in modified living conditions or the rehabilitated forms of Kali is in sync with our explanation. Without attempting to make our explanations excessively cynical for the emergence of controlling deities in turbulent times, such as the pandemic, we mark the ensuing scope of compensatory control in positive shades.

Before we close, we would also like to invite thoughts on the changing artistic representations of God over the past centuries. Could our explanations account for depictions of God that became more loving over time? We do appreciate that the living conditions have become less harsh or more predictable with the advent of public policies, sanitation and medical infrastructure. To the extent that the human race faces extraordinary occurrences, people’s need for order will nudge them to seek a safe shelter with their deities. The role played by polytheism summons further deliberation.

Bionote

Neha Khetrapal is an Assistant Professor at the Jindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences (JIBS), O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat, India. She is broadly interested in the role of ‘culture’ and ‘cognitive development’ in shaping religious thoughts. She is inclined to believe that her interest in the ‘Cognitive Science of Religion’ emerged from her passion for travelling.

Samah Nanda recently finished her undergraduate degree in Psychology (Honours) from Delhi University. She is currently interning at the Jindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences (JIBS) under the ‘Jindal Fellowship Program’ (O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat, India).

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.

References

Abrams, S., Jackson, J. C., Gray, K., Caluori, N., & Gelfand, M. (Poster). People’s Views of gods have changed Over Human History.

Bradshaw, M., Ellison, C. G., & Marcum, J. P. (2010). Attachment to God, images of God, and psychological distress in a nationwide sample of Presbyterians. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 20(2), 130-147.

Dein, S., Loewenthal, K., Lewis, C. A., & Pargament, K. I. (2020). COVID-19, mental health and religion: An agenda for future research. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23, 1–9.

Doehring, C. (2020). Coping with moral struggles arising from coronavirus stress: Spiritual self-care for chaplains and religious leaders. Chaplaincy Innovation Lab. Retrieved March 2, 2021 (link).

Falkner, D. E. (2020). Introductions to Other Mythologies. In The Mythology of the Night Sky. Springer, Cham.

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., McGregor, I., & Nash, K. (2010). Religious belief as compensatory control. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 37-48.

Khetrapal, N. (2020). Chants of Synchrony. Blog Post in CoronAsur, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. Retrieved from here.

Lee, S. A. (2020). Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Studies, 44(7), 393–401.

McNamara, R. A., & Purzycki, B. G. (2020). Minds of gods and human cognitive constraints: socio-ecological context shapes belief. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 10(3), 223-238.

Padma, S. (2011). Hariti: Village Origins, Buddhist Elaborations and Saivite Accommodations. Asian and African Area Studies, 11(1), 1-17.

Sales, S.M. (1972). Economic threat as a determinant of conversion rates in authoritarian and nonauthoritarian churches. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 23, 420–428.

Stroope, S., Draper, S., & Whitehead, A. L. (2013). Images of a loving God and sense of meaning in life. Social Indicators Research, 111, 25–44.

Srinivas, T. (2020). India’s goddesses of contagion provide protection in the pandemic – just don’t make them angry. The Conversation. Retrieved from the website of The Conservation.

van den Bos, K., & Lind, E. A. (2002). Uncertainty management by means of fairness judgments. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 1-60). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Thumbnail image courtesy of the author.