July 10-13, on the premises of the University of Ghana, Legon, in Accra, Ghana Studies Association organized its third conference. Themed “Ghana as Center”, the program revolved primarily around the mission of African Studies, as seen in the words of Pan-Africanist and first president of independent Ghana, Dr Kwame Nkrumah. In 1963, he said its mission would be “to study the history, culture and institutions, languages and arts of Ghana and of Africa in new African Centred ways”(1). Nkrumah’s perspective on the matter still echoes today, as in the same occasion he also stated that “African Studies, in the form in which they have been developed in the universities and centres of learning in the West, have been largely influenced by the concepts of old style ‘colonial studies,’ and still to some extent remain under the shadow of colonial ideologies and mentality”.

Stressing the geographical coordinates of Ghana’s capital Accra, that is well known to be located where the Greenwich Meridian and the Equator lines intersect, the conference aimed to place Ghana at the center of scientific and artistic imaginaries. Ghana’s territory has been a destination for researchers within the fields of social sciences for centuries now, spanning from colonial to post-colonial and neo-colonial times. A great amount of scholarship has been produced during this time, serving different purposes and reflecting different power structures. With many African Studies conferences happening outside the continent, at a time of brutal restriction of movement for non-white and non-European people, events like that held by the Ghana Studies Association show the possibility for a shifting of the horizon, toward another map of knowledge and theory production. As for many years, to study Africa meant to carry research informed by Western-centric methods and concepts, the conference has made a strong call in exhorting the attendees to take Ghana not as a destination, but as a departure point to develop new theoretical insights.

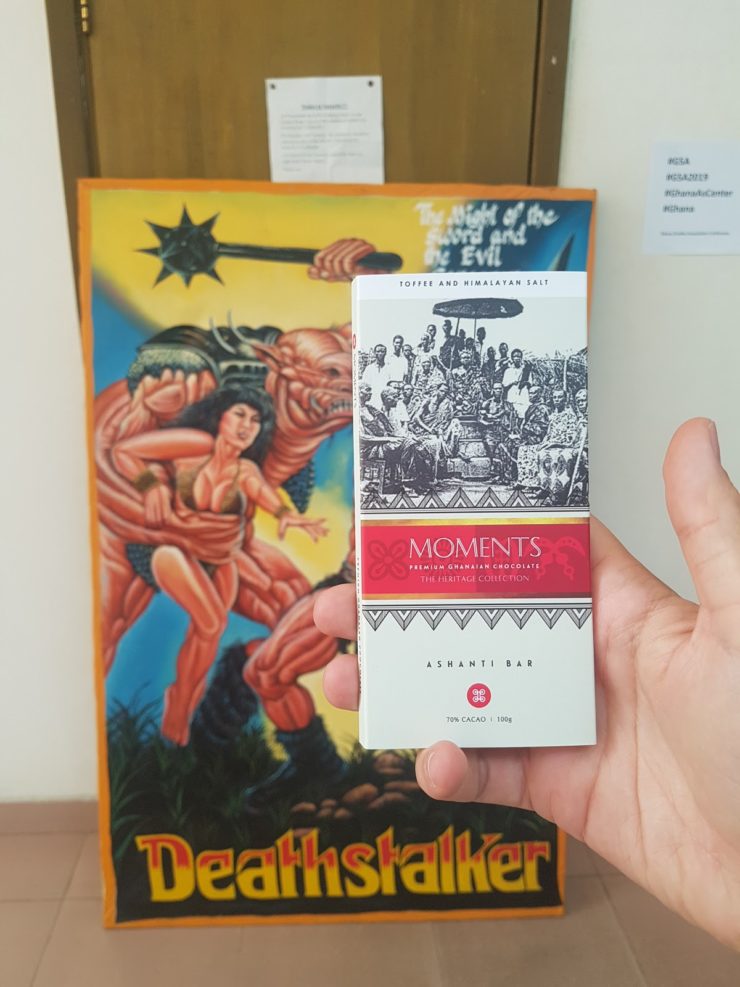

Premium Ghanaian chocolate bar. In the background a painted movie poster

from Joseph Oduro-Frimpong’s perosnal collection

The distinct fashion of the conference was distinguishable starting from registration when, instead of the usual semi-disposable tote bags, attendees were offered with an option: a stylish locally handmade fan or a selection of premium Ghanaian chocolate. I myself went for the chocolate, the “Ashanti Bar” with toffee and Himalayan salt. Figuring a historical photograph of the Ashanti chiefdom, it is part of a series called “Moments – The Heritage Collection”. Indeed, cocoa has been one of the main assets in the economy of the region, since its introduction. The bar iconically anticipated the keynote speech that was about to start. Delivered by Yao Graham, CEO of Third World Network, it touched the issues of economic development and structural organization of Ghana. It was a remark that moved along the ever-present tension between the much spoken democratization process of the country and the resilience of traditional chieftaincy.

A moment from Day 1

With a dominant presence of presentations about urban contexts (especially Accra), during the four days of the conference, a riveting stream of panels explored a variety of topics ranging from popular culture to infrastructural development, Pan-Africanism, decolonization struggles, religion, gender, education, and health care. But any attempt to recall the plurality of issues at stake in a comprehensive manner would be an act of hubris. I would rather subscribe to the aim of giving a taste of how things proceeded. Next to the classic panel format, there was a series of roundtables with invited scholars, artists and public intellectuals next to each other. For instance, at the end of Day Two, when Kobby Ankomah-Graham chaired a conversation with visual artists, writers and an architect sharing their take on Ghanaian identity. What is it, how does it change, what’s the role of the arts in it? It was a debate that moved on the edge of personal feelings, professional experiences, conflicting issues. A good sense of humour and provocative statements kept the audience’s attention up. A memorable peak moment came from Kuukuwa Manful who, asked to argue on the “meaning of being Ghanaian”, unapologetically replied “I don’t care!” A kick off moment that led to the next move: a bus ride down to the multi-layered Oxford Street to reach Republic Bar. Here, drinks made with local spirits fueled Kobby’s sonic lecture on the history of music in Ghana — from the world-celebrated Highlife to the most recent sounds of trap artists like La Meme Gang.

Kobby Graham’s sonic lecture

Kobby’s lecture was a landmark within the chronotope of the conference. The fusion of discourses, the usage of different media, the questioning of assumed categories in academic knowledge production. A thread that was developed later, in a roundtable titled “Epistemologies of Place and Identity” joined by Ben Talton, Abena Asare, Carina Ray, Ebony Coletu and Jesse Shipley: what is the role of the researchers in the construction of Ghana as a place? How could new paths of knowledge-making be pursued? The debate called attention to the North of Ghana, and how it figures into the country’s history. It asked how marginalized groups reinvent themselves, and drew out the tensions that arise from a too often homogenized concept of “Ghanaian identity”. New ways to frame and historically approach the study of colony and metropole were discussed, with the speakers agreeing on the usefulness to put the two within the same history, in conversation with each other. The pros and cons of academic publishing were also a matter of debate, with speakers both from the audience and the table agreeing in the need to also venture into more accessible formats.

The Madina project of our Religious Matters program joined the conference with interest and excitement, recognizing the affinity between the conference guidelines and the aim of our project to study religion not in but from Africa. Organizing a double session panel titled “Religious Plurality in Ghana: past and present”, it had the support of Ann Cassiman and Benedikt Pontzen who acted as discussants. The panel looked at the country’s plural configuration in terms of religion and its entanglements with other spheres of life, such as: food and market transactions (Rashida Adum Attah); access to health care (Martin-Luther Darko); beauty and body practices (Kauthar Kamis); all this moving from Madina area, whose historical frame was recalled by Samuel Ntewusu’s intervention on the genesis of the Madina district as a zongo (semi-informal settlement). The crossing of boundaries across different religious affiliation was also further explored, looking at the everyday life pragmatism among Islamic healers (Kodjo Senah), the debate around religion as a category among traditionalists (myself), the role of sounds in mediating religion public presence (Joseph Fosu-Ankrah), and the emergence of new forms of religious piety among young men in Accra suburbs (Emily Stratton).

Wrapping up the program, during the final dinner meeting, palm wine band Kwan Pa (‘the good path’) played live, bringing people to dance right up to the stage. A reminder of the need to keep questioning and challenging assumed categories of authorship, audience, performance and attendance.

Archiving this edition, Ghana Studies Association looks forward to the next meeting, that will be in Tamale, Northern Region, in 2022.

Final dinner at Zen Garden

(1) Kwame Nkrumah, The African Genius: Speech Delivered by Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah at the Opening of the Institute of African Studies, 25th October 1963 (Accra: Government Printer, 1963).