How is colonial history reflected in contemporary relations to mundane and otherworldly powers? And what role do moral assessments of materials play before that background when entangled with concepts such as good or bad death? Isabel Bredenbröker’s book ‘Rest in Plastic: Death, time and synthetic materials in a Ghanaian Ewe community’ which was published with Berghahn in the Material Mediations series edited by Birgit Meyer and Maruška Svasek gives fascinating anwers to these questions by means of ethnographic reflection. In Peki, an Ewe town in the Ghanaian Volta Region, death is a matter of public concern. By means of funeral banners printed with synthetic ink on PVC, public lyings in state, cemented graves and wreaths made from plastic, death occupies a prominent place in the world of the living. Rest in Plastic gives an insight into local entanglements of death, synthetic materials and power in Ewe community. It shows how different materials and things that come to shape power relations, exist in a delicate balance between state and local governance, kin and outsiders, death and life, the invisible and the visible, movement and containment. Birgit Meyer, who contributed a preface to the book that speaks from the perspective of not only a researcher on material religion but also as someone who conducted field research in Peki a few decades prior, speaks to Isabel Bredenbröker about the ideas and takeaway points that guided the writing. Isabel Bredenbröker, who currently works at Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, has been a visiting researcher at the Religious Matters project over the course of the past two years and previously presented the book during a lunch lecture at the department.

BM: How did you develop the idea for this research on funerals in Peki? Peki, by the way, is a place I know very well, as I conducted research there way back in the late 1980s and early 1990s and I still visit my remaining friends there regularly.

IB: I was basically thrown into it and had little time for planned development. Rather, the research focus evolved from my experiences in the field. I came to anthropology late, by means of changing subject with a second MA in the UK. My conviction in doing so was that it is not necessary to go to faraway places that are also far from one’s cultural upbringing in order to practice anthropology well. In other words, I was looking to do PhD fieldwork (on which this book is based) in Germany – not in Ghana, hereby linking me intuitively to the branch of our discipline which in Germany would be termed European Ethnology. However, the politics of academic funding wanted me to do otherwise and after over a year of working full time while trying to find money for my research I applied for, and was offered, a position in a graduate training group in Frankfurt that would focus on theories of value. Only in the interview did I understand that I was interviewing for a position with research based in Africa. Few months later, I was on my first trip to Ghana. I am critically addressing this backstory and the problematic politics of academic funding as well as Global North – Global South relations in academia in my preface in more detail.

In Ghana, on the other hand, I was completely free to choose any research topic I wanted and was immediately struck by the visually engaging and omnipresent funeral banners that adorn the walls of houses there. After choosing my site for research, Peki, a small town in the Volta Region, I decided to focus on the materials that become important for commemorating the dead, leading me ultimately to plastic and concrete, among others.

BM: How would you situate it in broader anthropological research on funerals?

IB: There are several studies on the role of not only funerals but also the social function of commemorating the dead in anthropology that are engaging and interesting, such as work by Marleen de Witte, Claudio Lomnitz, Erik Mueggler, Piers Vitebsky and others. In my book, while speaking about funerals, I try not to highlight these events as my sole object of study, but rather show them as intense moments where things to do with the dead can be shaped by the living. My work is inspired by the work of Gillian Feeley-Harnik, whose amazing ethnographic writing analyzes the ways in which a Malagasy community sticks to the rule of dead kings as a ‚political economy of death‘. Within a post-colonial setting, I seek to do the same in looking at contemporary Ghana.

BM: The title is “Rest in Plastic” – why did you choose that title? How is plastic important for current day funerals?

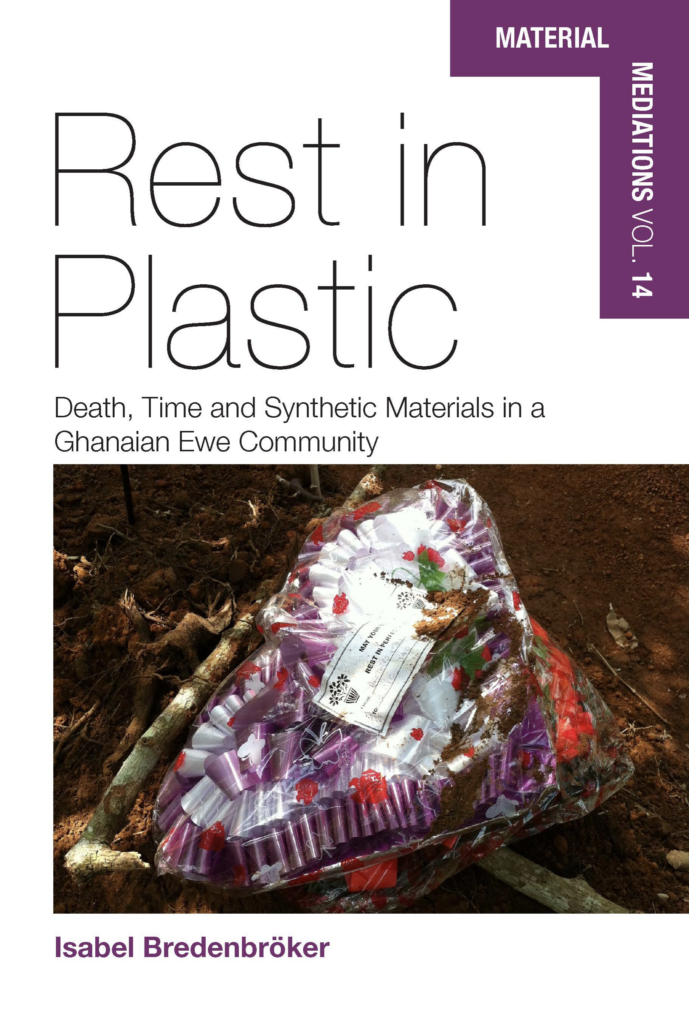

Grave wreaths, which in Peki are commonly made of plastic gift ribbon and cellophane foil, are usually adorned with a sticker that states: May you rest in perfect peace, to which the donor of the wreath can add a written dedication. Plastic and synthetic materials are omnipresent in funerals in the Ghanaian South and, in this context, are largely tied to positive moral qualities such as durability or respect. Hence, the title seemed an obvious choice and fun too.

BM: How did you conduct the research?

IA: I spent a total of 8 months in Peki, over three visits. While the first visit was needed to figure out where I wanted to go and what to study, I was fortunate to meet a great person, Collins Jamson, during this trip, who would come to assist me with the work upon my return. While in Peki, I assisted a local undertaker and attended close to 40 funerals – many funerals are bundled together over funeral weekends so one can hop from one event to the next. I also worked with designers of funeral posters, spoke to many local politicians, religious and traditional authorities as well as engaged citizens and did site-specific ethnographies of cemeteries and waste dumps – these are in fact connected! Last but not least, I shot the film Now I Am Dead (Journal of Anthropological Films, 2019) which looks at the nitty gritty of fieldwork in the middle of commemorating the dead.

Filmstill Now I Am Dead. Image credits: Isabel Bredenbröker, Phila Bergmann

BM: What, in your view, or the main insights offered by your book?

IA: Plastic and other synthetic materials are agents of a neo-colonial world order as they perpetuate inequalities that originated during times of Empire. Their often polluting and economically disenfranchising powers are in fact a problem for humanity and non-humans alike today. However, these materials must be understood not just as things that ‚cannot be local‘ as Heather Davis concludes in the wonderful book Plastic Matter (2022), but that synthetic materials must be looked as things that have been incorporated into very specific local worldviews and value systems – just like Christianity in Ghana which was imported as a Western missionary product initially and can today be said to have been acculturated, appropriated and transformed.

BM: How does your book push forward our understanding of religious matters in an entangled world?

IA: Things to do with the dead and the afterlife are always questions of religion, even if one, especially from a non-Western perspective, may choose to use different terms for beliefs and spirituality. The book highlights, by means of telling the stories of funerals in Peki, how materials, bodies, spiritual entities and social relations are entangled, locally and globally, to shape distinct power relations that evolve around how death can become morally ‚good‘ – and those who have died hereby ancestors.

BM: What are your future plans after having finished this project?

IA: I am currently finishing a postdoctoral research project that investigates queer relations and methods around ethnographic museum collections, culminating in an exhibition of the work ‚Queer Sonic Fingerprint’ together with sound artist Adam Pultz Melbye at Art Laboratory Berlin (19. October – 1 December). From 2024 on, I will be working at the Department of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies at the University of Bremen and set out to write my second book that will deal with swimming as a cultural practice and the ways in which swimming may allow for fluid moral and social categories. I look forward to delving deeper into environmental anthropology, a path onto which my book Rest in Plastic has already brought me without me noticing until it was finished.