Religious Heritage Network Symposium 2025

University of Groningen

Organizers: Andrew J.M. Irving (Centre for Religion and Heritage, RUG); Todd H. Weir

(Centre for Religion and Heritage, RUG); Birgit Meyer (UU)

Date: 3-4 December 2025

Locations: House of Connections and University of Groningen Museum (Day 1), University

of Groningen Museum, Faculty of Religion, Culture and Society, RUG, Groningen (Day 2)

Sponsors: Rijksdienst voor Cultureel Erfgoed (through the Religious Heritage Network);

Centre for Religion and Heritage; NOSTER; University Museum Groningen, Utrecht

University

To participate or for any questions, please contact: Austin Brewin (student assistant, CRH)

A.D.W.Brewin@student.rug.nl

Aim

Over the past years, both in scholarship and public debate, much attention has been paid to

the problematic provenance of collections of artifacts from areas colonized by European

powers. Across Europe, the publication of the Sarr-Savoy Report “The Restitution of African

Cultural Heritage. Towards a New Relational Ethics” (2018) had a strong impact on debates

about the past and future of colonial collections in the European museum-scape, triggering a

number of spectacular restitutions of artefacts, such as the Benin bronzes looted by British

military from the Kingdom of Benin, Nigeria, treasures looted from the court of the

Asantehene in Kumasi, Ghana, and the return of royal statues stolen by the French from the

Kingdom of Dahomey (masterfully documented by Mati Diop in the film Dahomey).

In the Netherlands, in 2020 the advisory report Colonial Collection: A Recognition of

Injustice was submitted to the government, and its recommendations were adopted in the

2021 policy document Beleidsvisie collecties uit een koloniale context, further supported in

2022 by a kamerbrief informing the Parliament on implementation of the policy. In research,

the NWA-project “Pressing Matter: Ownership, Value and the Question of Colonial Heritage

in Museums” (2020-2025) embarked on a detailed investigation of the provenance of specific

colonial collections in the National Museum of World Cultures and university museums in

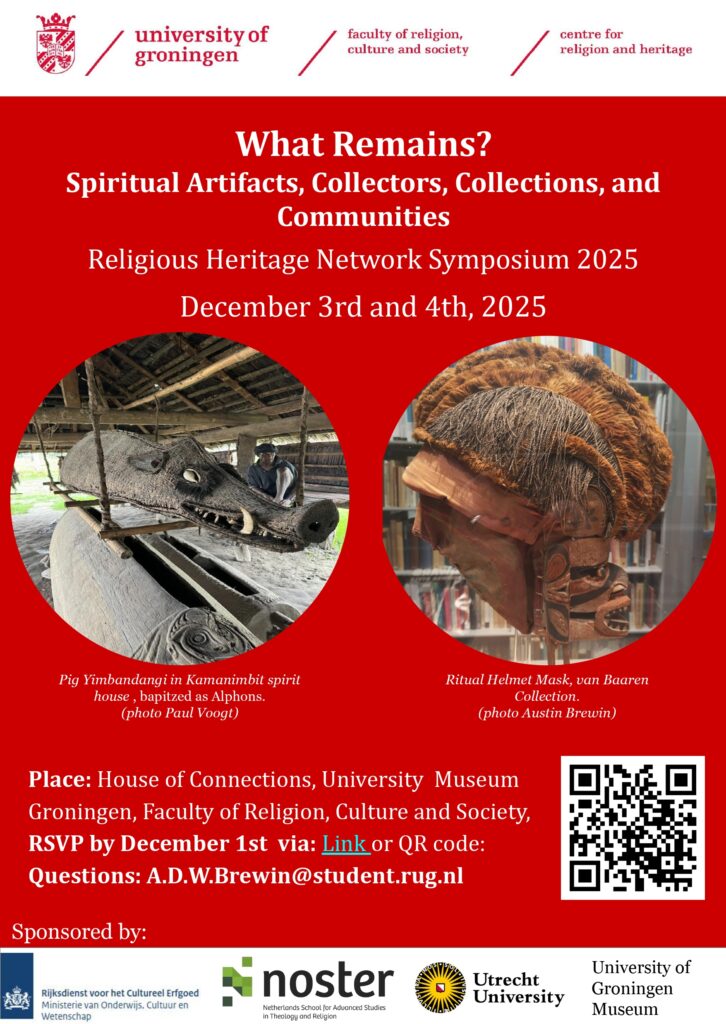

Amsterdam (Vrolik), Utrecht, and Groningen (including the Theo van Baaren Collection).

Against this backdrop, as scholars working on religion and heritage, we call special attention

to musealised religious artifacts. As (former) vessels of spiritual forces, representations of

deities, ancestors, animated materials or powerful devices, they have a special status that

raises pressing questions about the gap between the ways in which they were valued and used

in the communities of origin, on the one hand, and their storage and display in modern,

secular museums, on the other. Through which trajectories did they become part of museum

collections? Which role did Christian missions play in their collection, and their devaluation

as “idols” or “fetishes”? How did museum regimes of categorizing, storage and display affect

these artifacts? What impact did the collection have on the receiving institutions? To what

extent has there been an acknowledgement of their status as spiritual and potentially

animated? How could museums host such artifacts in a respectful manner? Is this impossible,

given the secular orientation of the Western museum?

Debates about provenance and the possibility of restitution have also raised questions about

the value and meaning of religious artifacts for the descendents of their makers and first

users. Often, the artifacts have been re-categorized in the “secular” museum by invoking

dismissive concepts drawn from the colonial and missionary lexicon. Old charges of

“idolatry” and “fetishism” may be powerfully resilient for today’s Christian beholders from

communities of origin. This shows the resilience and persistence of colonial and missionary

ascriptions.

In this workshop, we will explore how spiritual artifacts are viewed and dealt with as they

transition into and out of museum collections, both in Europe and in museums in the societies

from which the collections were taken. Which ideas and feelings do such artifacts evoke for

multiple beholders? How are they seen by Christian believers and theologians, especially in

the countries from where the artifacts hail? Are they still – or again- regarded as animated?

What happens if they are re-appreciated as “cultural assets” or “religious heritage”? How are

they treated in the museum context? In short: How do secular museum contexts – in Europe

and in the Global South – affect the meaning, value and ontological status of spiritual

artefacts and what remains of the powers imbued in them?

Format

We envision this workshop as a space for constructive, case-based discussions for scholars

and students. Accordingly, the two-day workshop is organised around five panels (each of

three 20-minute papers) and a student poster session. Each panel is thematically oriented in

order to bring into conversation five interested parties:

● The Collectors

● The Curators

● The Spiritual Artifacts

● The Theologians

● The Communities

Day One focuses on the creation of collections and the fate of artifacts in them: Panel 1

“Collectors; Panel 2 “Curators”; Panel 3 “Spiritual artifacts”. We ask how the artifacts arrived

in the collection, how was this documented, and perceived at the time of collection and

display? What were the motivations and interests of the collectors? How have curators

engaged with this legacy in their curatorial practice? What is the voice of the artefacts

themselves on these journeys, and how can they be made to speak? To what extent have these

collections intersected with reflection or spur new developments in religious studies and

anthropology? What about (new) animism as a conceptual framework?

Day Two focuses on the prospect of restitution and return of such spiritual artifacts from

Western collections to the states to which their former makers and users belong. How does

conversion to Christianity mediate current views towards such spiritual artifacts? How do

Christian theologians understand them? Is there a possibility to move beyond a resilient

Christian frame of “idolatry” towards “cultural heritage”? How do current – Christian and

non-Christian – members of source communities view and value such artifacts? In short, how

are differences between religious pasts and presents, differences which are often

characterized by conversions to new religious practices and faiths, mediated vis-a-vis such

collections?

The workshop also provides an opportunity for ReMA/MA/PhD student poster presentations,

to showcase student research projects on the topic, and provide an opportunity for

questioning, exchange, and networking.

Programme (provisional)

DAY ONE

House of Connections, Grote Markt 21, Groningen

10.00-10.30 Walk in

10.30-10.45 Welcome

10.45-12.15 Panel 1: Seekers and Collectors

Facilitator: Peter Pels, Universiteit Leiden, Birgit Meyer, Universiteit Utrecht

This panel is particularly interested in the motivations and the practices of collectors of

spiritual artifacts from cultures not their own. Two prominent collectors of ethnographic

objects who were also scholars of religion are central: Rudolf Otto and Theo van Baaren.

Rudolf Otto and the Founding of the Religionskundliche Sammlung in Marburg:

Concept, Acquisition, Musealization

Susanne Rodemeier, Philipps-Universität Marburg

Rudolf Otto (1869–1937), known for his groundbreaking work The Idea of the Holy (1917),

also initiated a lesser-known but equally significant project in studies of religion: the

Religionskundliche Sammlung, which was founded in 1927 on the 400th anniversary of the

University of Marburg. Unlike ethnographic or art historical collections, Otto’s vision

centered on comparative forms of religious expression. His aim was to create tangible and

emotional access to different forms of religious practice for academic teaching and research.

This talk explores Otto’s motivations and the scientific and institutional context in which the

collection was created. It sheds light on the process of acquiring objects, exhibiting

principles, and strategies used to visualize the diversity of religions. Beyond documenting

these aspects, the talk raises a further question: what significance does the collection have for

the research on materiality of religion? By focusing on the origins and conceptual

foundations of the Religionskundliche Sammlung, the talk aims to shed light on a topic that is

currently receiving renewed attention: the debate connected with religious artefacts

originating from missionary and colonial contexts, namely the question of object sensitivity.

Beyond Categories: An exploration of the Van Baaren collection at the Groningen

University Museum

Rosalie Hans, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

This paper will present some of the outcomes of the provenance research carried out in 2024

and 2025 on the Van Baaren collection in the Groningen University Museum (GUM).

Analysis of the Van Baaren collection made clear that the categories of ‘university

collection’, ‘missionary objects’, ‘art’ and ‘ethnography’ do not accurately describe the

variety of objects (or artefacts) brought together by Van Baaren nor his motivations and

collecting practice. Looking beyond these often used categories will allow for a better

understanding of the collection as a whole. This will be illustrated by several case studies

from his collection, with an emphasis on objects he acquired from missionary orders. It has

been assumed that Van Baaren’s vocation as a religious studies scholar and surrealist poet and

visual artist informed what he acquired for his collection. However, a more layered image

arises from his archive: that of an opportunistic collector well-connected to the ethnographic

art networks across Europe, who was consulted as an expert and had a keen eye for

commercial value and museum interests. His involvement with brokering acquisitions

between congregations and museums are of particular interest. The paper will consider what

this could mean for how Van Baaren viewed religious artefacts and what has happened to the

interpretation of the collection since it became part of the GUM in 2003.

12.15-13.15: Lunch

13.15-14.30 Panel 2: Curators and Conservators Part A

Facilitator: Dr. Sabina Rosenbergova, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

This panel explores the new challenges as the collected objects enter museum collections.

How has the museum acknowledged, (dis)respected, disregarded, or obscured the persistent

spiritual nature of the artefacts? What are the implications for display, access, preservation

and communication?

Curating Living Asmat Artefacts

Andreas Wahyu, Asmat Archive

This paper reflects on the curatorial challenges and ethical issues involved in exhibiting

Asmat artefacts at the Asmat Museum of Culture and Progress in Agats, Papua. The Asmat

people do not simply understand their carved objects as material creations, but also as

embodiments of ancestral presence and communal memory. However, when these artefacts

are transferred to museum collections, both local and international, their spiritual vitality is

often reframed through aesthetic or ethnographic categories that diminish their ritual

significance.

Based on my experience of curating the permanent exhibition at the Asmat Museum of

Culture and Progress, as well as my visit to the World Museum in the Netherlands, this paper

explores how different museological contexts engage with, or fail to engage with, the

persistent spiritual dimensions of Asmat cultural objects. I discuss how Catholic inculturation

in the Asmat region has produced a unique cultural synthesis where ritual woodcarving,

Christian symbolism and collective memory coexist and shape new understandings of the

sacred.

Through this reflection, the paper considers how curatorial practices can acknowledge the

continuing life of artefacts — beyond preservation and exhibition — and create a dialogical

space that honours indigenous cosmologies while addressing asymmetries of power and

museum representation.

Interests, relationships, pathways and missteps: Handling spiritual items of the Ewe

people from the collection of missionary Carl Spiess at the Übersee-Museum in Bremen

Silke Seybold, Übersee-Museum Bremen

In 1893, the young Heinrich Schurtz began working as an ‘ethnographic assistant’ at the

Museum für Natur-, Völker- und Handelskunde in Bremen. In the same year, he published an

article on ‘Amulets and Magic Devices’. [Heinrich Schurtz: Amulette und Zaubermittel, In: Archiv für Anthropologie, Völkerforschung und kolonialen Kulturwandel, 1893, S. 57-64.] And when he met missionary Carl Spiess in 1896, who was obviously fond of collecting, a close relationship developed between the missionary and the museum. Schurtz expressed the wish that Spiess should pay particular attention to amulets and magic devices. And Spiess fulfilled this wish. Over the next 20 years, he

collected many items for the museum in the mission area of the Norddeustche Missions-Gesellschaft in West Africa (today’s Togo and Ghana): natural history specimens, written information, but above all more than 500 objects, many of which have a spiritual connection.

In my contribution, I would like to trace how this collection has been and continues to

be preserved, researched, presented and communicated in the museum, which is now called

the Übersee-Museum Bremen. What continuities or breaks have there been over the years?

What interpretations and misinterpretations? What interests did and do those involved have,

and what relationships influenced and continue to influence the work? How is the historical

context reflected? Special attention will also be paid to the Legba-Dzoka project, in which

scholars and practitioners from Togo, Ghana, Germany, and the Netherlands are working

together on the provenance of the Spiess collection and its significance for people in West

Africa today. One focus is on spiritual objects. What influence does this cooperation have on

everyday museum life and how the collection is handled today?

14.30-14.45 Break

14.45-16.00 Panel 2: Curators and Conservators Part B

Facilitator: Sabina Rosenbergova, Rijskuniversiteit Groningen

The possibility of a future: the Marind collections at the Wereldmuseum

Fanny Wonu Veys, Universiteit Leiden

Collected by missionaries and anthropologists, the collections from the Marind in southern

New Guinea held by the Wereldmuseum relate to the performance of dema-stories. These

large-scale rituals staged primordial beings, dema, in order to establish a connection with the

ancestral beings of the forest. Via regular visits to the sago gardens and the forest connections

with ancestral family members present in plants, animals and stones are nurtured. However,

because of the rapid spread of oil palm plantations since 2010, and now also the advance of

rice fields, the relationship with ancestors is difficult and sometimes impossible. This paper

explores how these collections represent Marind life worlds through the intervention of

anthropologists and missionaries but also the role museums can play in discussing

multinational capitalist economies and current Marind views on these objects. Is there a

possibility of creating a future if the connection with your ancestors has been impeded?

Rethinking Ancestors beyond “Religion” and Toward “Heritage”

Peter Pels, Universiteit Leiden

Africanist anthropologist Igor Kopytoff took a decisive step beyond the North Atlantic

concept of “religion” in his famous “Ancestors as Elders” (1971). The article suggested that

the North Atlantic tendency to treat deceased ancestors as either “supernatural” imagination

or dead matter, thus reducing their effects on the living, produced a stark boundary that

Kopytoff’s interlocutors’ among Suku did not articulate. Revered elders passed into

ancestrality, but not just by the sudden rupture of death – they lost their personhood as elders

after death and burial, gradually becoming less of a person and more of an abstract presence

as they receded from memory. Kopytoff thus questioned whether certain core assumptions of

the modern concept of “religion” applied to African forms of revering ancestors.

In this essay, I want to apply this “Africanist” analytic – without presuming it covers the

whole of “Africa” (whatever that may be) – to North Atlantic genealogies of heritage. This

should test the hypothesis that ancestrality is equally common in North Atlantic cultural

circuits as in “African” ones, but that its connection to “religion” is obscured by the tendency

to hide that monuments have similar afterlives, both in positive and negative ways. I employ

several examples from the history of the French Revolution, where some of the most central

assumptions about modern heritage – assumptions that determine UNESCO heritage

conventions to this day – emerged. The essay concludes by considering the thesis whether the

nineteenth-century monument can be interpreted as a typically modern form of ancestrality.

16.00-16.45 Walk to Faculty Library and then University Museum (Oude

Boteringestraat 38 and Oude Kijk in het Jatstraat 7a)

16.45-17.45 Panel 3: In the Presence of the Artifacts

Facilitator: Birgit Meyer, Universiteit Utrecht

This experimental panel attempts to attend to ongoing agency of the spiritual artifacts. With

permission of the University Museum, Groningen, it will take place in the museum, and in

the presence of objects from the Theo van Baaren collection. It explores how we can allow

room for the artifacts itself to communicate and thereby shape curatorial, scholarly, and

community practice inside and outside the museum walls, for instance through performance.

What if these are beings?

Nii Ocquaye Hammond and Marleen de Witte, Universiteit Utrecht

Moving from reflecting on a museum collection to consulting the spiritual entities whose

images are held therein, this performative intervention unfolds among artifacts from the Theo

van Baaren Collection. Through symbolic gesture, sound, invocation, and collective

presence, the performance invites ancestral entities to awaken as living participants rather

than mute objects. By ritually opening the space to their agency, it provokes reflection on

their stature, their journeys of violation and displacement, and their promise of reconnection

and nourishment. What happens when spiritual artifacts are no longer treated as objects of

study but as beings in conversation? The performance creates a space of encounter where

museum, scholarship, and ancestral presence intermingle, calling participants to listen –

intellectually, sensorially, spiritually – to the voices that remain.

17.45-18.45 Student Poster Presentations and Borrel

MA, ReMA, and PhD students present their research on topics related to the symposium’s

theme.

Reception

19.30 Conference Dinner for presenters

DAY TWO

Location: University Museum

9.30-10.45 Panel 4: Re-collecting what was lost Part A

Facilitator: Lieke Wijnia, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

How do local communities of origin perceive and engage with the return of spiritual objects?

What remains of the former musealisation and categorization? What new challenges arise

from de-museualisation or re-musealisation in new contexts?

An Uncomfortable Possession. Modelled Skulls in a Mission Museum and their Spirits

Paul Voogt, curator Missiemuseum Steyl

The Missiemuseum Steyl exhibits five modeled skulls from the Sepik-area in Papua New

Guina, from the collection of the missionary society of the Divine Word (SVD). They are an

uncomfortable possession for the congregations in Steyl. The Missiemuseum decided to

investigate whether the skulls could be returned to Papua New Guinea. But the residents of

the communities of origin do not want them back.

According to the people in the source communities, the objects have lost their spirit when

they left their community. But the spirits might return when they return to their place of

origin and the people do not know how to handle them safely anymore.

The Missiemuseum currently investigates different options to deal with this heritage, as part

of the temporary exhibition The Collection Resists. One of the options is presented by Dicky

Takndare and Albertho Wanma, contemporary artists from West-Papua.

The dilemmas surrounding this uncomfortable possession will be highlighted in this

presentation.

Rebuilding the Cosmic Centre: The Asmat Longhouse as Ritual and Resistance

Dr. Jaap Timmer, Macquarie University – Sydney

The jee, or longhouse, is the cornerstone of Asmat culture. Serving multiple ritual functions,

it symbolises the cosmic centre, linking the earthly realm to the upperworld where ancestors

dwell. The cyclical rebuilding of the longhouse every five years is the most significant ritual

act in Asmat society, an ethical obligation that maintains cosmic and social order. Since the

1950s, this tradition was violently disrupted by Catholic missionisation, Dutch colonial

governance, and Indonesian assimilationist policies. Longhouses were burned, rituals

suppressed, and sacred knowledge fragmented. Yet over the past two decades, renewed

interest in the longhouse has emerged. Supported in part by the Catholic Church and driven

by local aspirations for cultural autonomy, many communities have begun rebuilding

longhouses. This reactivation, however, is shaped by generational ruptures, forgotten songs

and techniques, and the broader afterlives of colonial and missionary regimes. In this paper, I

explore the longhouse as a spiritual artefact that remains embedded in Asmat cosmology but

now circulates through altered ontological conditions. What does it mean to ‘recollect’ a

sacred form not from a museum but from disrupted memory? And what remains when a

spiritual object is rebuilt not with intact tradition, but in the shadow of colonial fracture?

10.45-11.15 Break

11.15-12.30 Panel 4: Re-collecting what was lost Part B

Facilitator: Lieke Wijnia, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Re-collecting dzoka

Birgit Meyer, Universiteit Utrecht

At the center of this presentation is the research of the Legba-Dzoka project, an

interdisciplinary and international group of scholars and two vodu-priests, who focus on a

collection of spiritual artifacts kept in the Übersee-Museum Bremen. They were taken there

by Protestant missionary Carl Spiess who preached the Gospel and collected artifacts from

the Ewe-speaking area around 1900. Recently, our team presented the outcomes of our

provenance research to a broader public in Ghana and Togo, from where the collection

initially hails. In this presentation, I will discuss multiple positions formulated vis-a-vis the

possibility and desirability of a return of the items in the collection to Ghana and/or Togo,

ranging from downright rejection in the name of “idolatry”, to recognition as valuable

cultural assets and forms of heritage, to an their embracement as spiritual forces. Arguing that

these positions evolve around the secular-religious boundary, I will pay special attention to

the notion of heritage, which is situated at the core of that boundary.

Art, Heritage, or Religion? The Restitution of Vigango Memorial Posts of the Mijikenda

to the Religiously Diverse Context of Coastal Kenya

Erik Meinema, Universiteit Utrecht

Vigango (plural, singular is kigango) are wooden posts that Giriama and other Mijikenda

people use to represent deceased male ancestors who were members of the Gohu fraternity.

While a few vigango where collected during colonial times as ethnographic

objects, vigango gained recognition as East African art during the 1970s and 1980s. In

relation to this newly acquired status, many vigango were stolen and/or sold to art traders and

collectors, and subsequently ended up in museum collections across the globe. In recent

decades, Mijikenda activists, scholars, and Kenyan government institutions have been

involved in attempts to return vigango to Kenya. In this presentation, I explore how different

parties involved in these restitution efforts use the globally circulating frames of ‘art’

(usanii), ‘heritage’ and culture (utamaduni), and ‘religion’ (dini), and how these frames relate

to different (ownership) claims that are made about vigango. In addition, I explore if and how

these frames leave open the possibility of recognizing vigango as vessels of the spirits of

deceased ancestors.

12.30-13.30 lunch at RCS (Oude Boteringestraat 38)

13.00-15.30: Panel 5: Past Religions and Decolonization: Religious Heritage and

Contemporary Theology in the Global South

Facilitator: Professor Todd Weir, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

This panel explores developments in theological discourse (systematic, missiological,

pastoral, liturgical) concerning sacred images and practices belonging to non/pre-Christian

religious traditions. In particular it asks: What is the response of pious Christian or Muslim

members of communities of origin to the return of their “lost” spiritual heritage? How does

“heritage” figure in efforts of theologians from the global south to establish new relationships

to the “indigenous” religious heritage of their ancestors?

Return of Lost Spiritual Heritage: A Response of Pious Akan Pentecostals

Bismark Agyapong, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Akan religious beliefs and practices intertwines with its culture. Although Akan Pentecostals

generally practice their newfound beliefs in opposition to their indigenous religion, remnants

of their cultural identity are always kept. It is then the very interest of this paper to ask the

question what is the response of a pious Akan Pentecostal to the return of their lost spiritual

heritage? A vast majority of Akan Pentecostals incline to a theological viewpoint that is

incompatible to their indigenous religion. These Pentecostals, for example, perceive their

salvation as a radical break from their “past,” i.e., vestiges of indigenous religious beliefs and

practices. Despite this positionality of the vast majority of Akan Pentecostals, there is also a

growing number of Akan Pentecostals who have renewed appreciations for their “past.” As a

methodology, I focus on existing literary scholarships particularly on Birgit Meyer’s work

“Make a Complete Break with the Past: Memory and Post-Colonial Modernity in Ghanaian

Pentecostalist Discourse” and oral narratives collected through recent conversations with

some devout Akan Pentecostals in Kumasi, Ghana. These sources are thematically analyzed

in view of interpreting theologically the return of lost Akan spiritual heritage. This paper

analyses how some Akan Pentecostals engage with spiritual vestiges of the past, not as

sacrilege but as insights into Akan spirituality for theological re-evaluation. This paper argues

for a contextual Pentecostal theology that perceives the “past” as a resource for constructing

an authentically Akan expression of Pentecostal Christian faith. As an Akan Pentecostal

theologian, I propose that the return of lost spiritual heritage is not a threat, but as reflective

inroads for the contemporary Akan Pentecostals in understanding the historical body of

beliefs conceived among the Akan people of old. This paper contributes to a deeper discourse

on faith and culture, decolonial theology, and African Christian identity in current religious

contexts.

Three Perspectives on Sacred Traditions of Indigenous Kachin People

Zung Bawm, Protestant Theological University

This paper, a work-in-progress chapter of my PhD research, outlines three main perspectives

on the sacred traditions/practices of indigenous Kachin people of Myanmar: (1) discontinuity

or demonization, which rejects all indigenous traditions out of fear of syncretism and a

theology rooted in human exceptionalism; (2) divergence, which advocates for a total return

to lost indigenous religious traditions by romanticizing pre-Christian Kachin beliefs as an

antidote to Westernized Christianity, coupled with an ecological critique of the Bible and

Judeo-Christianity; and (3) appreciative discovery, which fosters a constructive and creative

dialogue between Christian theology and life-affirming indigenous traditions, allowing these

to be interpreted through reformulated Christian theological lenses to enhance the relevance

of the Christian gospel message.

Aligning with the third perspective of appreciative recovery, I briefly engage three

ecologically relevant concepts from my green exegesis of the three parables in Mark

4—where Jesus presents the earth/γῆ as a key character to articulate the ecologically resonant

message of the kindom of God—in dialogue with analogous pre-Christian Kachin traditions:

human kinship with the earth, the earth as a living, nurturing entity, and the earth with

prophetic agency. This intercultural exchange seeks to cultivate a culturally sensitive,

earth-oriented biblical interpretation that enriches ecological theology and offers fresh

insights for restoring humanity’s relationship with the earth and caring for God’s good

creation amid the pressing global and local ecological challenges of the Anthropocene era.

Shrunken heads and Evangelical radios, or the complications of heritage on

Shuar territory, Ecuador

Victor Cova, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Shuar people and neighbouring members of the Chicham linguistic group used to

ceremonially reduce the heads of their enemies captured in war, producing artefacts that

became very popular among European and North American primitivist collectors. In recent

decades, these artefacts have become problematic in European and North American museums

both because they are human remains and because of their religious nature, and efforts have

been made to repatriate them. Yet Shuar institutions that receive those artifacts often do not

know what to do with them, in parts because most Shuar people consider themselves

Christian, even if not always practicing ones. In this paper I will discuss the contemporary

ambivalence of Shuar people towards shrunken heads, and compare it with the equally

difficult memorialization of Christian missions on Shuar territory, and with some

anthropological perspectives that see memorialization itself as contrary to Shuar culture.

15.30-16.00 Break

16.00-16.45 Closing Discussion

Chair Todd Weir, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Mirjam Shatanawi, KITLV and Reinwardt Academy (Amsterdam University of the

Arts)

Birgit Meyer, Universiteit Utrecht