Adriano Godoy

On December 10th, 2020, I defended my Ph.D. dissertation entitled “Cultivating the House of Mary: materialities of the National Basilica of Aparecida”. It was supervised by Professor Ronaldo de Almeida in the Graduate Program in Social Anthropology at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and received funding from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP). Between 2018 and 2019 I had the opportunity to participate in the Religious Matters in an Entangled World Program as a visiting researcher under the supervision of Professor Birgit Meyer.

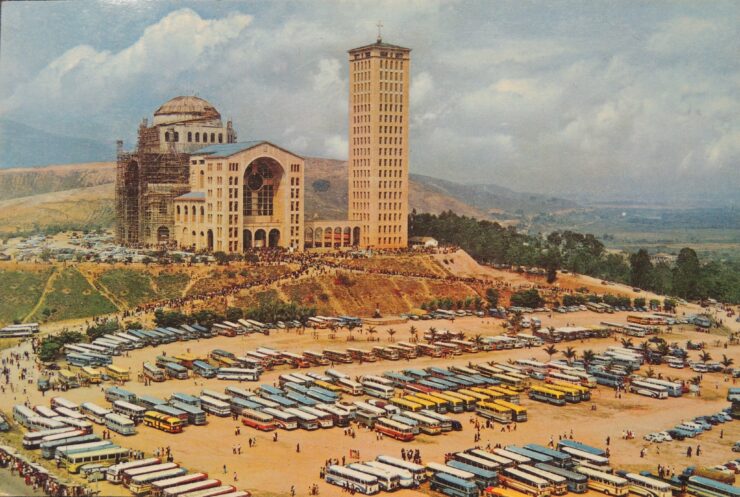

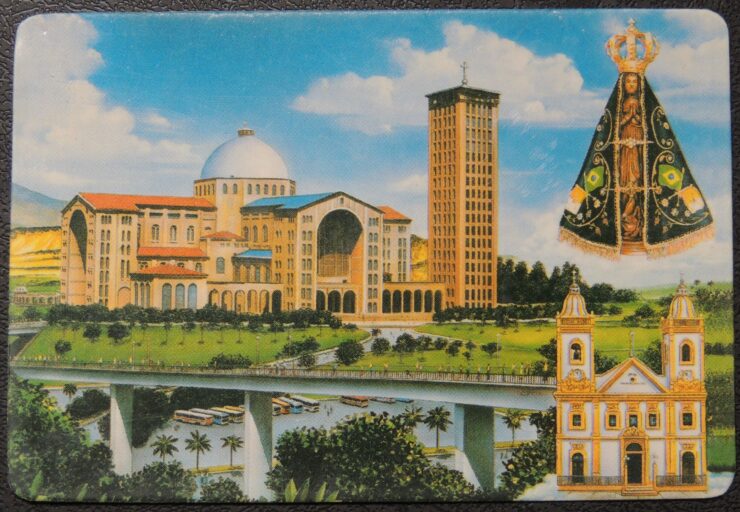

For better contextualization, the field research was developed primarily between 2015 and 2019. During this period, I made a series of visits to the National Shrine of Aparecida, located in the city of Aparecida, in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. Interested in the ongoing process of building the Basilica, as I will explore later, my focus was to attend all the religious ceremonies that took place for the inauguration of the works in progress in the church. But not only that. The Basilica of Aparecida had its first stone laid in 1955 and, since then, construction has not stopped and its conclusion is not in sight, which led me to do a series of researches in archives, both in Aparecida and in the Vatican, for a broader understanding of the trajectory of this building.

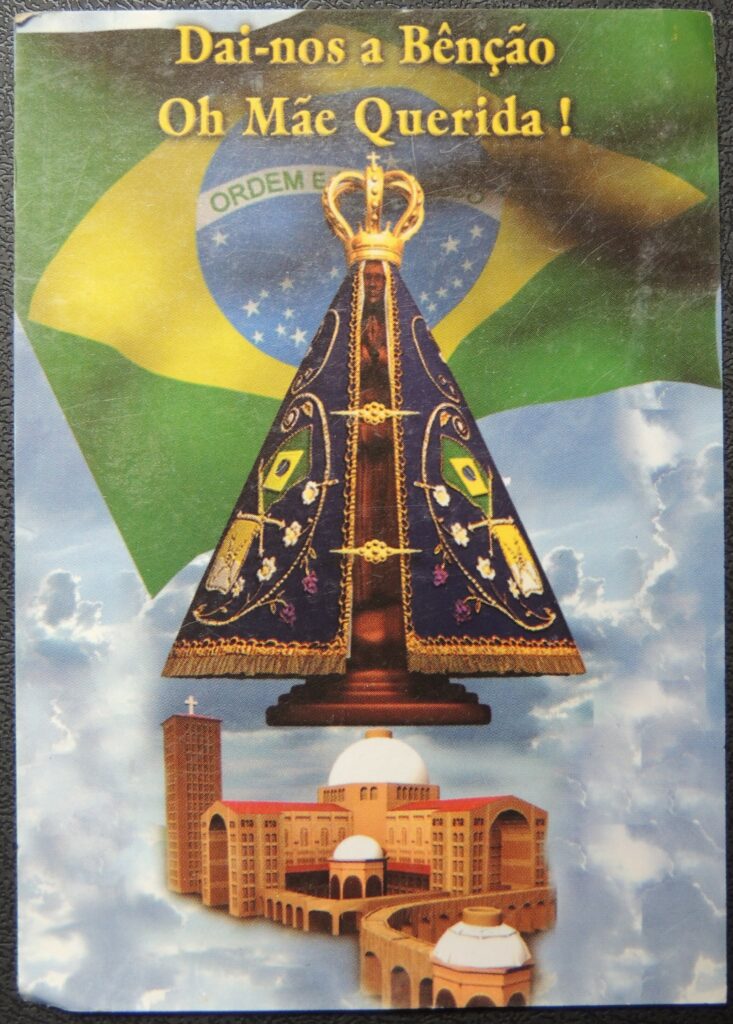

Taking into account this long and vast trajectory of the Basilica, my methodological option for writing the dissertation was to refer to the present. I chose the year 2017 as a point of analysis because it was precisely in that year that the 300th anniversary of the apparition of the miraculous statue of Nossa Senhora Aparecida (Our Lady Aparecida) was celebrated. For this reason, a series of great commemorative events took place in her shrine, events that had as their focus the inauguration of new celebratory spaces within the church. Interested precisely in how, why and by whom the whole church is made, the ethnography that structures each of the thematic sections in my dissertation refers to one special night: October 11th, 2017, eve of the three hundred year mark, night when the central dome of the church was inaugurated and the saint received a new crown. In the words of the clergy, two great gifts from devotees to the anniversary queen.

The chapters are organized in three sections: I – The Lot; II – The Facade; III – The Nave. As the titles indicate, they look into these three areas of that shrine, that correspond with the different ways in which the Basilica is built. Far from defending a rigid distinction between the inside and the outside of the church, I intended to demonstrate through ethnographic work how these two spaces are relational. At the end of each section, there is a series of images within the respective themes that are an independent and complementary visual narrative to the topic addressed.

Chapter 01 – A Catholic forest -, opens the first section of the dissertation and aims to introduce the places and methods of the field research. By compiling the congresses I attended and the archives I visited, I present the source of the materials I quote in the course of the dissertation in addition to those related to my daily experiences at the Shrine of Aparecida. I was able to examine documents at the Metropolitan Curia Archive of Aparecida, at the Documentation and Memory Center of the National Shrine and at the Vatican Secret Archive. All this ethnographic material is approached by the forest metaphor to propose a convergent approach with the field of Material Religion. With the metaphor of the material forest, I try to emphasize how the religious practices and experiences in that place are intrinsic to the great plurality of things, objects, constructions, folders, and papers that shape the church daily.

at the central altar

In chapter 02 – Making the Garden -, I analyze how the Catholic Church manages this same forest in several fronts to organize it institutionally, through an exercise of control and stabilization of these materialities. Thus, I present the construction project of the Basilica of Aparecida as the production and cultivation of a garden. With that, I try to demonstrate that of all the things that make up that shrine, there are only a few chosen to be both made and transformed by the Catholic Church, which aims to have control of the religion that is practiced there, on their own terms. The Basilica of Aparecida would then be a splendid material garden grown inside and in relation to the forest that characterizes the shrine.

In the second section – The Facade – the chapters deal with how the construction of the church was made so that it could be seen from the outside and from the places where its presence is marked. Thus, in chapter 03 – The insufficiency of the church and the crown – I address the political inspirations for the title of Aparecida as queen and patroness of Brazil. Contextualized to the ultramontane movement, in which Brazilian Catholicism is Romanized, I discuss how the new titles for the saint spatially and geographically impacted the places she inhabited, especially her old church, the Old Basilica. This small church on top of a hill, over time, has become insufficient because it did not support the growing flow of pilgrims and because it was not aesthetically convincing in its mission. Likewise, the crown of Aparecida that was donated by Princess Isabel, representative of the Brazilian Empire at the end of the 19th century, was exchanged in 2017 for a crown donated by devotees. The saint’s reign was thus updated to new times.

In chapter 04 – Big and beautiful like Brazil – I discuss the colossal size of the new Basilica of Aparecida. Contextualizing the architectural project of Benedito Calixto de Jesus Neto, hired to build the second-largest Catholic church in the world, I show how over time (between the 1950s and 1970s) it was decided that it would be the largest in the world, surpassing the Basilica of Saint Peter in Rome. Thus, the monumentality of that building is my key to analyze how it materializes the projection of the place in which the Catholic Church positions itself in the Brazilian national imagination. With patriotic propositions, that is, seeking a Brazilianness expressed by architectural forms, I bring as a counterpoint its original inspiration in the National Basilica of Washington, in the United States. Nowadays there is a parallel of competition in size with other religious buildings in Brazil, such as the Temple of Solomon, a headquarter of evangelical Pentecostalism in the city of São Paulo.

Section three – The Nave – addresses the changes in the internal setting, both artistic and pastoral, which takes place from the 2000s with the administration of Cardinal Lorscheider. That is how in chapter 05 – The iconoplastic modernization – I deal with the hiring of Claudio Pastro, in the late 1990s, as the artist responsible for the modernization of that church. In my opinion, in a period marked by a certain neo-Pentecostal iconoclasm in the country, enhanced by the decrease in the number of people who identify as catholic nationally, the solution found by the artist and the clergy is a neo-Byzantine iconoclasm. This marks the new artistic project, which included profound transformations from the niche of the saint to the canopy around the altar. The artist, who was an expert on the norms dictated by the Second Vatican Council, rejected the national baroque tradition and had as aesthetic reference, instead, the first millennium of Christian art, mixing both a Byzantine aesthetic with what he calls primitive art, inspired by Amerindian and African art. I argue that through the National Basilica, the artist manages to propose and create an update on Catholic modernism.

at her golden niche

In chapter 06 – Mother’s house, family of devotees – I demonstrate how the use and construction of the temple, alongside with the newly hired artistic project, seek to transform the church into a maternal home. I do this by analytically approaching the fundraising campaign created for its construction, which until then had depended on voluntary and sporadic donations. In the campaign to raise funds for renovating the central dome of the church, for instance, I explore how the house, as an anthropological category, is essential to understand the religion practiced in that place through pastoral action. In this proposal, carried out by the clergy under the leadership of Archbishop Nicioli, who led the administrative changes, a certain entrepreneurial outlook becomes the new norm, which, also allegedly inspired by the Second Vatican Council, aims to create a community of devotees that identify themselves as a family. A conciliatory counterpoint with the ecclesial communities of Liberation Theology as well as with the covenant communities of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal. In an architecture that materializes the house of all devotees, the proposal of a home merges with both the Catholic body and the Brazilian nation.

Finally, in the epilogue, I explore the inauguration of the central dome. In the new project, it was finished with a tile mosaic of what is called the tree of life, surrounded by birds found in Brazilian territory. It is from the considerations made by Pastro that I return to the metaphor of the material garden. I state that if the Basilica is a garden, what my research has shown is that it is built by careful landscapers – just like Pastro and Calixto Neto – but daily cultivated by gardeners, like the priests. As Archbishop Nicioli told me in an interview, one of his missions is to keep the church alive, to ensure that it does not die, and, in order to cultivate this religious dynamism, it is necessary to continuously build it. Thus, what I tried to explore was how the fabrication of Catholicism, through materials and practices, is made explicit in the construction and maintenance of the Basilica of Aparecida. This takes place in a mutual religious relationship between the temple, its administrators, the artists, and the pilgrims, and it gains shape through the relationship of the tangle composed by different missionary fronts and a plural crowd of visitors under the same dome. And there would one find its implicit beauty: a diverse collection of materialities that gain such conglomerate shape when it is cultivated. In this movement in search of the eternity of the Catholic temple, time is also a fundamental category. Being susceptible to adaptations and responding to the short- and long-term Catholic demands, these architectural materialities need to take on a religiously persuasive form continuously.

To analyze the construction of a church through its material forms is thus to approach these mutual movements of religious cultivation. My dissertation seeks to explore, within a certain framework, some of the possible mediations that are practiced through that building that is administered by the Catholic Church. Without a deadline for the conclusion of the construction of the Basilica and because it is allegedly “a living church”, with each new architectural work that is announced in that space, “sensational forms” are also materialized, overlapping practices of Catholicism and nationalism. Without completely replacing or excluding previous forms, it is through these new aesthetic formations and through its plurality of correlated materialities that Catholicism is fabricated in architectural layers in the Basilica. These, in turn, are experienced both outside and inside the church, closely and from afar, with guides or without maps, in partial ways, but never in its totality.

Bio note

Adriano Godoy is a researcher at the Laboratory of Anthropology of Religion (LAR-Unicamp). He has a PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Campinas (Brazil) and was affiliated to the Religious Matters Program in 2018/2019 as a visiting researcher.

Photos by Adriano Godoy