Jerrold Cuperus

“We also sell old church statues, ask about it at the desk”, reads the sign on the antique wooden closet. On top of the closet, which is tucked away behind a brochure stand in the museum lobby, are three statues: Saint Joseph with the child Jesus, a Sacred Heart of Jesus, and Saint James the Great, all over two feet tall. The museum, which is set in a former convent chapel, is filled with hundreds of other statues which formerly belonged to churches. The manager of the privately-owned ‘Museum Vaals’ also owns a shop where he sells those statues and items for which his museum does not have enough space. Located on a busy street near the edge of the town of Hoensbroek, a thirty-minute drive from the museum, the aptly named ‘Relimarkt’ evokes a vastly different aesthetic experience from the statue museum. In the museum, the door creaks when you enter, and the overwhelming richness of colors is complemented by the smell of incense and old wood, while loud choir music fills the chapel. The shop window display, on the other hand, is clean and white and prevents passers-by from peeking into the store. A market stall is set up behind the window and contains various paintings, devotional items, and a couple of statues. It communicates the purpose of the establishment effectively: this is a place to buy ‘religious’ antiques.

Figure 1 The interior of Museum Vaals

Upon entry into the store, I am still unable to see what is being sold. The bell rings when the door closes behind me and the volunteer at the desk asks me to pay the €2,- entrance fee. Is this a museum after all? I am granted access to the store and walk into a space which reminds me of a museum shop: candles, rosaries, and small statuettes of saints and Jesus are neatly stacked on shelves. Turning to my right I walk into the actual Relimarkt. Five or six market stalls are set up front and center in the large (8000 sq/f) hall. Along the walls of the hall is a red-carpeted ‘stage’ with hundreds of statues, most of them over one meter tall. Every Saturday and Sunday a handful of people come in to buy statues, tabernacles, stain-glass windows, altar bells and gongs, paintings, and lithographs. Other people pay the entrance fee and walk around for a bit, and drink a cup of coffee in the church pew-furnished café section of the establishment.

Figure 2 The ‘Relimarkt’ market stalls

The first question coming to mind is: how did all this stuff end up here? Owner Gert de Weert started collecting statues decades ago. Intrigued by the fact that, in a flea market, he could haggle over the price of Jesus and Mary – something that contrasted with his protestant upbringing – Gert assembled a collection of over a hundred statues in his house before he was able to exhibit them at Museum Vaals. The surplus items which are not suitable for his museum, he sells in the Relimarkt in order to finance his hobby of collecting more and more precious statues for his museum.

Many of the items that are available to collectors today, have ended up on the market as an effect of the Second Vatican Council, which convened in the 1960’s and profoundly changed many Roman Catholic liturgical and devotional practices. Statues, gold and silver, mosaics, and paintings were thrown out of Dutch churches to make room for a more inwardly focused experience of faith. During this ‘exodus’ of church art, many statues were demolished – a priest I interviewed described how gypsum statues were turned to rubble and used to fill the pond in the backyard of a church near Utrecht. Passionate collectors at the time were able to acquire entire church interiors for a low price, and sometimes even for free. This dynamic differs significantly from the current moment, wherein a nostalgia is found for these objects and where a longing for this very specific aesthetic experience of Catholicism becomes apparent. At the same time, a rapid ‘de-churching’ has taken place in the Netherlands. Religious affiliation and church attendance have been on the decline, meaning that church buildings have to be demolished or repurposed as well, leading to even more objects becoming available. However, these items from churches do rarely end up on markets, since they are protected by heritage and church institutions and often repurposed in other churches in the Netherlands or abroad. Devotional items, on the other hand, are abundantly available on antique markets.

Most items found in the Relimarkt or stores like heiligenbeelden.com and Fluminalis – a company selling and renting out entire church interiors with a worldwide clientele – moved from the church to the market during the period directly after the Second Vatican Council. Nowadays it is only occasionally possible for collectors and entrepreneurs to acquire some items from churches or monasteries which have to close down, but most church and monastery inventories are currently monitored by heritage agencies. With religious affiliation and church attendance being on the decline, who at all would be interested in these items?

Having walked around the Relimarkt for a couple of days, and regularly visiting online auction sites such as marktplaats.nl, Catawiki, and Facebook marketplace, I noticed that many people are indeed interested in these objects. Collectors and private individuals looking to furnish their café’s and homes, Catholics looking for items of devotion, and clergy looking to re-furnish their churches, and the occasional researcher in Religious Studies all come to see and buy items available on these markets. Depending on the material from which they are made, statues can go for hundreds if not thousands of euros, gold- and silverware are sold in similar price ranges, copper candelabra and incensories regularly sell for prices ranging from dozens to hundreds of euros. A priest from the opposite end of the country came to visit the store, looking for a gong to replace his older one. The owner told me about clergy from neighboring countries buying items to furnish their churches. Fewer and fewer nuns, monks, and craftspeople are around to make new items, and churches rarely have the money to have new items made. Second-hand stores like the Relimarkt are therefore essential suppliers for churches.

Apart from clergy and passionate collectors of church art, the store is often visited by people with an emotional attachment to the art and objects. As Daan Beekers has written on this website, people who regularly use church buildings attribute value to them primarily because of the emotional connections that they maintain. When a church closes down, its users lose a part of their ‘home’ and that hurts. The same goes for church objects. “The faith of people is in [those things],” said the priest that I interviewed, “because it was used in a worship service, or it was just present in the church, and people have, consciously or unconsciously, fed their faith with it in one way or another”. A sense of sacredness is imbued in church objects, which proves difficult to remove. The Facebook page of the Relimarkt illustrates this perfectly. Every few weeks, the owner posts a number of pictures of new items that have come in. In between the hundreds of comments with people tagging each other and asking the price of specific objects, we can find expressions of awe (‘gorgeus!’; ‘beautiful statues’) and people commenting with praise and worship (‘Thank You Jesus for everything in my live Amen’). These online expressions of awe, together with some of the responses I observed during my time in the store, acknowledge that these items still convey the beauty and a sense of sacredness. This means that the sacredness of these objects is not bound to the setting of a church, but extends into other contexts as well.

At the same time, one can imagine that finding the items formerly belonging to your ‘home’ in the church in an antique shop may still hurt. For many beholders, ‘sacred’ items do not belong on the market. Devastating (verschrikkelijk), is the word the priest used when I asked him what he thinks of church items ending up in antique shops. “For me, the ecclesiastical value remains attached to it”, he said. This statement shows that he deems this ‘ecclesiastical’ value to be incompatible with the market value of a church item. According to the priest the meaning of a church object in the setting of a church is vastly different from the meaning of the very same object in the setting of an antique shop. For exactly this reason, the Utrecht diocese, for instance, requires churches which have to close down to collaborate with a specialized department of religious heritage museum Catharijneconvent in order to repurpose church objects to other churches or museums, preventing them from ending up on the market. Interestingly, the same priest is also a customer of various antique shops where he regularly finds and buys church and devotional items in order to ‘rescue’ them from the market.

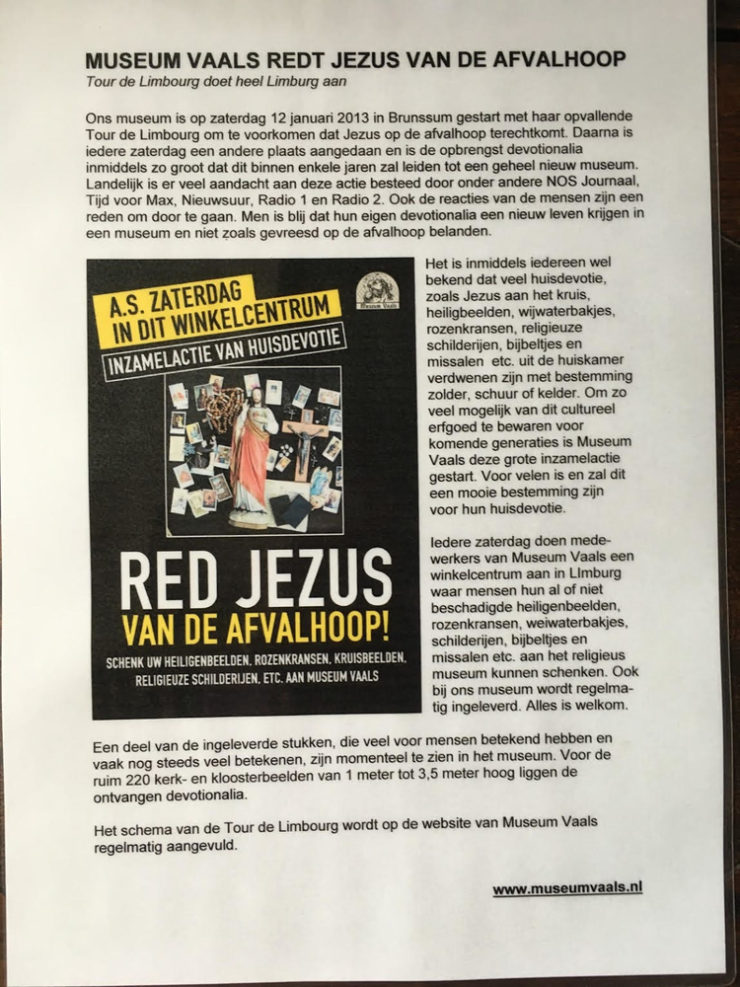

Figure 3 Flyer ‘Rescue Jesus from the Trash’

A few years ago, Relimarkt owner Gert also tried to rescue statues and items – not from ending up on the market, but from ending up on the garbage heap. With his campaign ‘Rescue Jesus from the Trash’ (Red Jezus van de Afvalhoop) he traveled to Dutch malls where people could come and donate their excess statues, rosaries, prayer cards, and the like. Over the course of the campaign, Gert collected over 300 moving boxes full of church and personal devotional items. At the time of writing, most of these collected items are stored in the basement below the Relimarkt, waiting to be sorted out and to be exhibited in a new museum which is to be opened soon – the items are not for sale. When speaking to Gert and his volunteers in the Relimarkt store, they often emphasize that, first and foremost, they are museum people not skilled in the ways of the market. The Relimarkt, the owner argues, is primarily meant to finance his hobby of collecting more and more beautiful art for his museum(s). During moments when the store is not crowded, the volunteers maintain the art by polishing copper, retouching gypsum statues with some paint, or organizing lithographs on theme and quality. The market, in this way, also preserves the church heritage, both through maintenance and by circulating the goods.

Figure 4 Statuettes in the basement of the Relimarkt

The Relimarkt proves an interesting case to study because history, heritage, religion, and economy come together in one and the same space. Coming across this store pointed out for me that an entire market of religious heritage exists in the Netherlands. This markets only exists because, 50 years ago, there were some people who cared deeply about the art that was subsequently thrown out of churches because of liturgical reforms. A nostalgia for the times before this ‘exodus’ by clergy and parishioners of Roman Catholic churches gives these items a new significance. A nostalgia for the very specific aesthetic of before the second Vatican council, often referred to as het Rijke Roomse Leven (the Rich Roman-Catholic life), is apparent. Moreover, in recent years an increased focus of the importance of religious heritage by national officials such as minister of Culture and Education Ingrid van Engelshoven has become dominant in public discourse, with over half of the national monument restauration budget going to (formerly) religious buildings. The ‘year of religious heritage’ in 2009 kickstarted a political lobby which reinforced this discourse. An increasing focus on heritage also changes the reason why these items are important. ‘The faith of the people’ which the priest believes to be imbued in church objects, has made way for nostalgia for a bygone era. Although the sacredness of these items seems hard to remove, their meaning is susceptible to change. By centralizing these church objects and looking their trajectories, we can see transformations in meaning which in turn tell us a lot about the changing society where these transformations take place. A society which revalues and reshapes Christianity from a religion which some choose to follow, into a part of national heritage and identity which is – at least in theory – open to all.

Biography

Jerrold Cuperus recently graduated from the Research Master Religious Studies at Utrecht University. His thesis, ‘The Sacred Lives of Things: Revaluing Church Objects as Heritage and Commodities’, investigates how objects from closed-down Roman Catholic churches in Utrecht are revalued and repurposed in museums and antique markets. Currently, Jerrold teaches religion and philosophy of life in Dutch secondary education and works as a research assistant on the project ‘Beyond Religion vs Emancipation’ at the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies.