Through advertisement, urban areas of contemporary Ghana offer opportunity for vibrant and plural healing practices. As Kodjo Senah (a Professor of Sociology, University of Ghana), shows in his contribution in this gallery, along major highways, small streets and open spaces, digital printed and hand-painted billboards and posters contest for public space in the urban areas of the country.

From these forms of representation, the aesthetic paradigms of Ghanaian visual communication (Cristofano, 2014) in targeting a vast range of chronic and degenerative illnesses and diseases may be appreciated.

These images express the highly diverse setting of Ghanaian society, revealing how different traditions and therapeutic trajectories interact and compete with each other in the public domain. However, as Senah reiterated in his presentation entitled “Healing Practices Across Religions”1, this development is a complete departure from what obtained during the colonial era, when the British administration passed the Native Customs Regulation Ordinance (1878), under which a number of local practices and traditional healing were banned.

The ban forced healers to remain in rural areas or to operate secretly in the cities. However, after Ghana became independent in 1957, the new nationalist leader desired a Ghanaian state with a unique political identity that incorporated many traditional icons into the aesthetics and politics of state formation. Thus, the state-induced formation of a national healers association was aimed among others, to promote the state philosophy of African Personality as a rallying cry for Africans and African in the Diaspora (Senah, 1997).

Although these attempts were not entirely successful, in later years promotion of traditional healing came to focus on investigating the medicinal properties of herbal products (Acheampong & Vasconi, 2010). Therefore, over the years, new herbal clinics operated by Christians and Muslims have emerged mostly in the urban areas of Ghana and are being used by Ghanaians across the religious divide. Indeed, as Senah has noted, pharmaceutical products have “been so integrated into the local therapeutic regimen that they have become cultural products” (1997:209). The same can be said for herbal products. Indeed, in people’s everyday life, different treatments are not mutually exclusive but “they overlap given the processual nature of illness” (1992:138).

As a consequence, traditional healers no longer operate in obscure places as before and most of them now rely on street advertisements to show the ailments they can treat. Next to these so-called traditionalists and Muslim healers (mallams), this collection of photographs by Kodjo Senah offers a view of the giant-size billboards through which different Christian churches publicly promote their healing practices.

A painted wall on an old building capturing a doubled-faced Ghanaian – a Christian and a Muslim – who seeks the services of a traditional healer in times of difficulty.

Centre for Scientific Research into Plant Medicine, established in 1976 in Mampong Akuapem, Ghana Eastern Region.

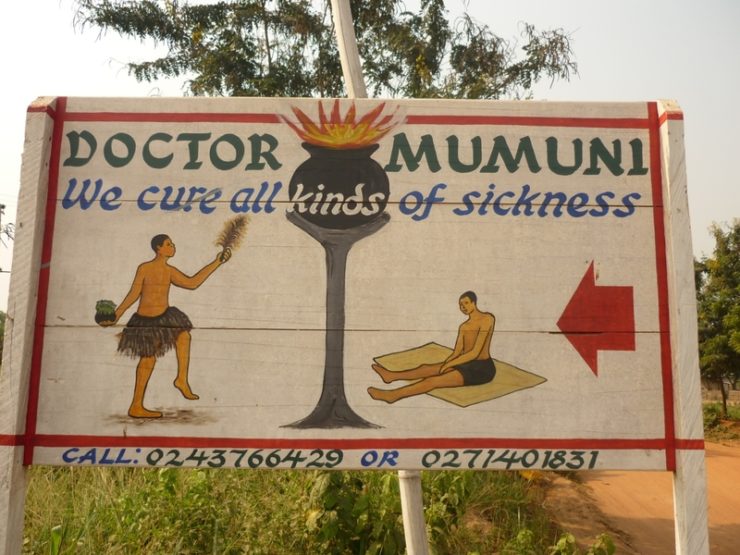

A signboard advertising the services of a traditional healer

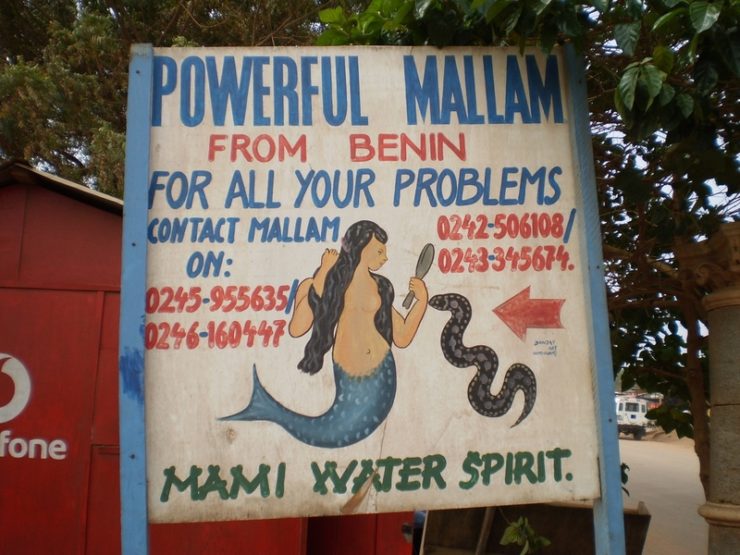

Street signboard of a Mallam who relates his services to mami Water, a mermaid spirit known to live in the bottom of the sea

In this hand-painted plywood a traditional healer offers help for both spiritual and physical issues

A parked van showing signs of a herbal centre, selling products in one of the main market of Accra

A giant digital-printed billboard advertising natural food supplements for men

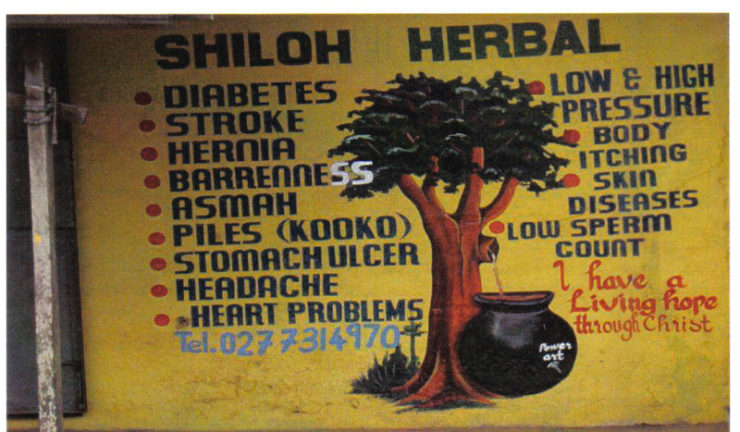

Painted wall listing the series of diseases treated by this herbal centre

A sign pointing to a muslim herbal and spiritual centre.

Hand-painted signboard graphically illustrating the diseases treated by Messiah Herbal Centre

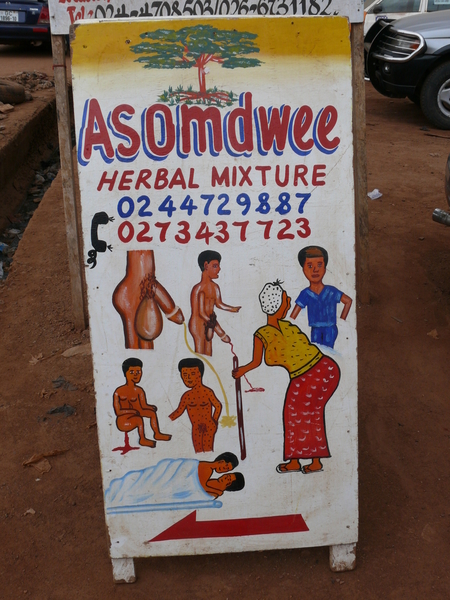

A plywood signboard showing realistic reproductions of different diseases

Herbal centre advertising its products along the street

Street signboard explicitly addressing fertility problems

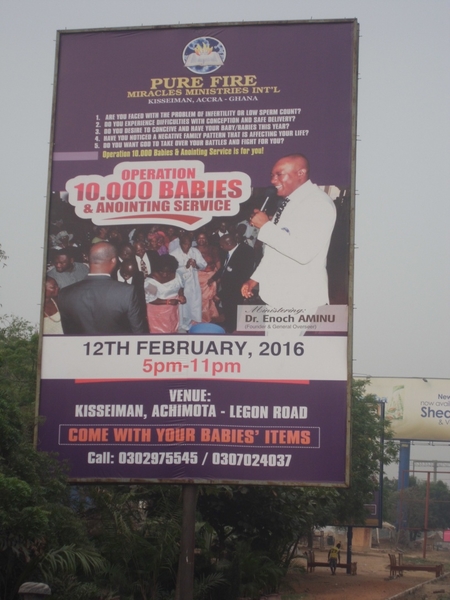

A big billboard in which a christian religious leader launches a campaign for married couples who have no babies

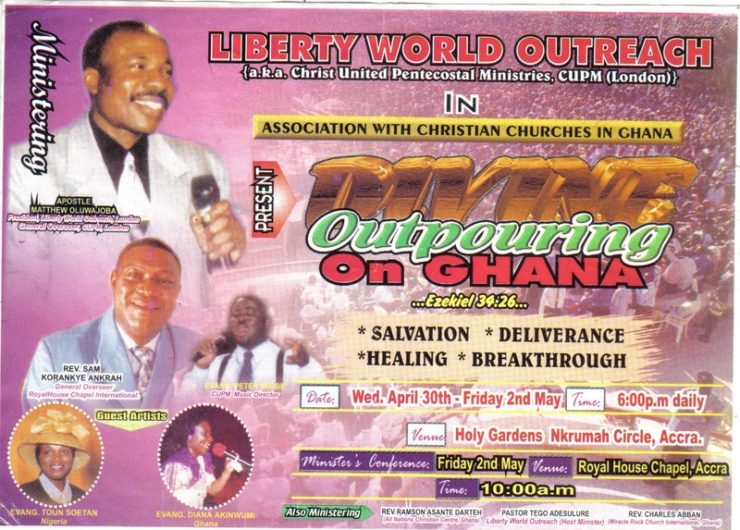

Digital-printed billboard of a Pentecostal Church service for salvation and healing

Giant-size billboard calling for church service to solve fertility related problems

Another signboard showing a Pentecostal pastor advertising a conference to help couple conceive

Street banner calling for “Hour of Pregnancy”

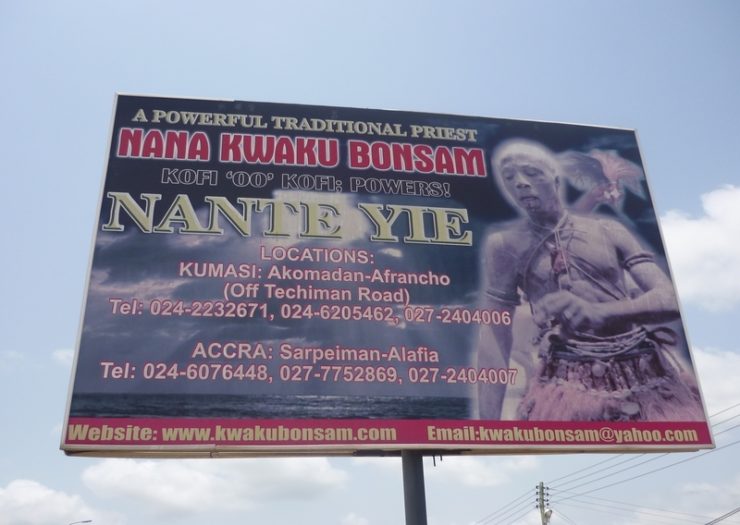

A giant digital-printed billboard showing Nana Kwaku Bonsam, a traditional priest who entered the public domain challenging Christian leaders

- Kodjo Senah presented this research in the context of the workshop ‘ Modalities of Co-Existence: Conviviality, Collaboration and Conflict Among Muslims and Christians in Diverse Urban Settings’ held at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, 3-5 April 2017.

References

- Cristofano, M. (2014). Signwriters in Ghana – from Handmade to Digital. Critical Interventions, 8(3), 304-330.

- Senah, K. A. (1992). ‘You Devil, Go Away From Me!’Some Ethnographic Comments on Evil Diseases in a Ghanaian Village. Etnofoor, (1/2), 129-145.

- Senah, K. A. (1997). Money be man: The popularity of medicines in a rural Ghanaian community. Het Spinhuis.

- Owoahene-Acheampong, S., & Vasconi, E. (2010). Recognition and Integration of Traditional Medicine in Ghana: A Perspective, link.