The Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, the former colonial museum and one of the major ethnographic museums of the Netherlands, has opened an exhibition titled Longing for Mecca, on the Islamic pilgrimage, the Hajj, that attracts millions of believers annually. This exhibition is based on the 2012 Hajj journey to the heart of Islam at the British Museum, and was subsequently adapted for a Dutch audience in 2013, and exhibited at the National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden. Longing for Mecca is now on display once again in Amsterdam till February 2020.

In the meantime, the four ethnographic museums have been consolidated into a single National Museum of World Cultures, which also acquired new objects. Having quicker access to a larger collection, the Hajj exhibition has been improved in a subtle way, displaying objects that underscore the global diversity of modern and contemporary Islam, while focusing on Dutch Muslims and the Dutch colonial past as well.

As I was previously involved in documenting some of the objects as an assistant curator, I was especially curious to see the changes made to the objects on display, and would like to briefly share a few thoughts I had after seeing the exhibition.

First, why an exhibition on the Hajj at all, why now, and why in the Netherlands? It should come as no surprise that the museum is keen to attract young people of various backgrounds, and the exhibition in Leiden did just that. I remember visiting the same exhibition in Leiden with a Dutch-Turkish-Moroccan couple, who were not religious per se, but identified more or less with Islam, and visited the museum in Leiden for the first time thanks to the exhibition. Now that the exhibition is in Amsterdam, one expects that even larger crowds will be drawn.

The purpose and “mission” of the museum, as it is often labelled, was clarified by the director, Stijn Schoonderwoerd, at the official opening of the exhibition on Valentine’s Day: bringing people together, defending open-minded thinking, and generating greater tolerance and mutual respect in the Netherlands. Such a view was repeated by Wouter Koolmees, the Minister of Social Affairs and Employment, who had been invited to cut the ribbon. For Koolmees, such exhibitions serve the purpose of “integration” as a form of soft power – promoting greater social cohesion based on the idea that “contact” between different people can help achieve that. In fact, Koolmees expressed his wish that the museum would function as a place which is “less political,” in his words, than the everyday arguments citizens and politicians have in the public sphere. He stressed the needs of young visitors – many of them children – who can visit the museum to learn about an important Islamic ritual, which matters to Muslims all across the world including Dutch citizens. The museum shares this goal with the Minister, to act against polarized understandings of Islam in society. On the other hand, it is well known that the exhibitions of the Tropenmuseum betray a critical interpretation of the concept of “integration,” especially in the culturally nationalist ways it has been used in the Netherlands of the 21st century. While the minister spoke of Muslims as Dutch citizens, rather than “allochthons” or as “others,” he cannot yet afford a post-integration discourse. In any case, whether the exhibition is too political or depoliticized, at first sight I found this difficult to determine, a promising conclusion given the mission of the museum and the sensitivities of the subject.

Secondly, what struck me during the opening presentations, and throughout the exhibition, was the emphasis on personal experiences, indicated also by the title, Longing for Mecca. Jihad Alariachi, for example, spoke about her near-death experience surviving a plane crash and consequent pilgrimage to Mecca as something that gave her the feeling of being “reborn.” Most of the short videos of Dutch Muslims of diverse backgrounds explaining about the Hajj emphasize “love,” “the heart.” and “sincerity,” which reminded me of Charles Taylor’s Varieties of Religion Today: William James Revisited (2003, Harvard UP). According to Taylor, religious experiences in our time do follow a Jamesian model of personal faith, but he criticizes a too narrow focus on the individual for neglecting entanglement with and the enduring importance of social practices and institutions. Taylor therefore concludes that, to understand religions today, both the emphasis on the psychology of individual experiences as well as Durkheimian analyses of sociological functions remain crucial for the varieties of religious experiences in a secular age. The exhibition’s emphasis on personal faith follows such a vision, and informs visitors about the visual, aural, and tactile atmospheres, objects, and sensations that are part of the simultaneously collective experience that is the Hajj.

Next to the emphasis on the human experience, the objects are used to demonstrate the pluriformity of the Hajj. Visitors are informed that, in fact, most pilgrims hail from Asia, from Turkey and Iran to China and Indonesia. The goal of the exhibition, as is often the case with exhibiting Islamic art, is to promote a “cosmopolitan” – a term used in the exhibition – vision of Islam and of Muslims according to which Mecca can also be seen as serving the function of a unifying center, i.e. a synthesis of the ideas that there are many Islams and that, for Muslims, there is simultaneously a real sense of unity and oneness of God and of Islam. Former curator Mirjam Shatanawi’s book Islam at the Tropenmuseum (2015, LM Publishers) can offer visitors and interested students and scholars more information about such theoretical considerations, and the influence of debates in the anthropology of Islam on the museum’s different displaying styles and strategies.

I cannot describe the many beautiful objects here in detail, including the precious loans from the Khalili Collections, so I will give only two examples of new acquisitions on display for the first time, both first acquired by professor emeritus Frederick de Jong (Utrecht University) and bought by the museum in 2015.

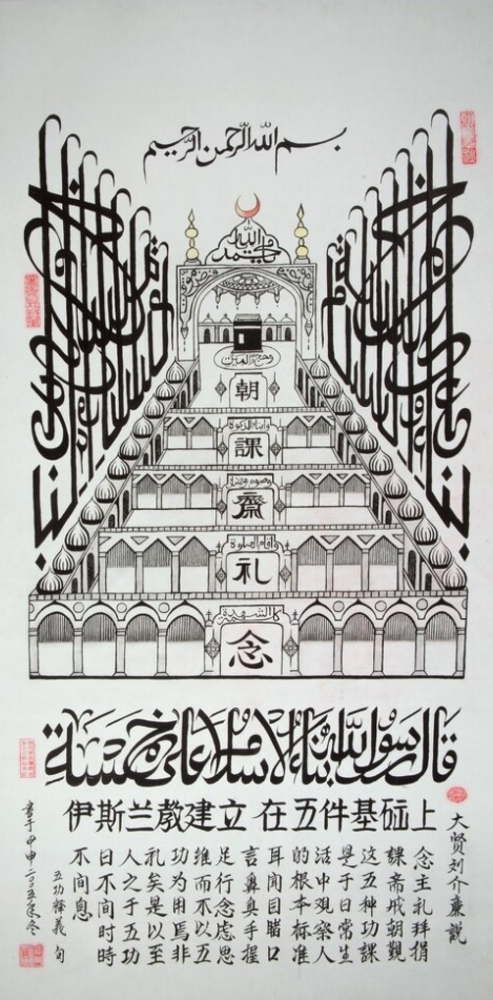

The calligraphic composition made by Shi Jie Chen (1925-2006), also known as Muhammad Hasan Ibn Yusuf, is striking because it reveals immediately and visually how Chinese and Arabic text and architectural elements are fused by the artist who lived in Ürümqi, was visited there by de Jong, and who did not live long enough to witness the current totalitarian policies of the Chinese state. The theme of this work is traditional, showing the five pillars of Islam, but in a way that will be unknown to many visitors. In fact, when this object was documented, a new category of “Islamic styles and periods – East Asia” had to be created in The Museum System, the software used by the museum, because it was the first of its kind in the Dutch collection.

Shie Jie Chen. 2005. Sino-Arabic calligraphic composition of Five Pillars of Islam. Ürümqi, China. Inventory number 7031-3. National Museum of World Cultures, The Netherlands.

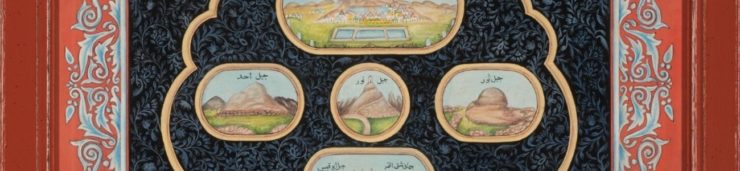

Another more unusual acquisition is a work signed and dated 1322 AH (1904-5) by Bilal Azizof, working in Tobolsk, Russia. The gouache shows the mountains of the Hijaz, where key events in the life of the Prophet Muhammad took place, from receiving his first revelations to his final sermon on Mount Arafat, which is one of the sights where pilgrims gather during the Hajj. Museum visitors will probably fail to notice the uniqueness of the contrast between the light blue of the depicted mountain skies and the background filled with blue flower motives and black, a color composition and style that hints at the Siberian origins of the work.

These and other art works and ethnographic objects, some more traditional, some more modern in style, are used in the exhibition to showcase Islamic pluriformity. Next to geographic diversity, the displays and accompanying texts make sure to mention other religious differences, that there are mystical strands in Islam, for instance, or by showing objects that belong to Shi’ism, although the overall impression the exhibition gives remains that of a Sunni Islam of the Five Pillars, the Qur’an, and Islamic Law, even as this is at times combined with other voices, such as the musical performance by Karima El Fillali during the opening on February 14.

The exhibition has also included works that could provoke critical thought, such as information about restrictive Dutch colonial governance policies aimed at controlling Indonesians (though the extent and nature of these policies are not made very clear), or a picture of the many skyscrapers of contemporary Mecca with a critical question: is it possible, here in Mecca where vast amounts of wealth and power are accumulated, to truly achieve spiritual purity and universal equality? These critical insertions– through visual works of art and short object descriptions – remain modest, so as not to harm the social and cultural mission of the museum to function as a peaceful and amicable contact zone, and can be overlooked without much difficulty by visitors longing for an aestheticized vision of Mecca.

In my opinion, it is an achievement to convey something of the beauty of the Hajj to visitors of various backgrounds. However, in doing so, negative aspects are blended out. The museum collection holds, for example, a nineteenth century lithograph of black slaves, musicians, who performed in Jeddah (next to their instruments, and wax cylinder sound recordings), which could have been shown. At the moment, visitors are not given any information about what appear to be black servants depicted in one of the exhibition’s historical pictures printed on one of the walls. We do get a glimpse of such pasts through a series of photographic portraits by Adel Quraishi of the last “Guardians” of the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. These men are the last of a tradition that involved the castration of black enslaved men, who were trained to be the keepers of the Prophet’s burial chamber. By writing that these practices are quickly becoming history, however, with a general emphasis on the mostly positive feelings that believers reminisce, the exhibition shows that the goal of attracting Muslim visitors, to promote “contact,” has the paradoxical effect of not willing to touch the exploitation and abysmal human rights record of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, not just in the past, but also in the present. Visitors are told, to give one more example, that meat produced for Eid al-Adha, the Feast of the Sacrifice, is distributed to the poor around the world. But what about the notorious exploitation of migrant workers, also in Mecca? The exhibition displays the numbers of the gargantuan logistics involved in the Hajj, but these function more to amaze viewers than to prompt critical thinking, for instance by zooming in on issues of the environment or the destruction of heritage sites. And, what about crackdowns against dissidents, or brutal punishments such as the bizarre “crucifying” of the dead body of a man convicted for murder, after beheading him, for the public to see in the Mecca of 2018, just days before the Hajj began?

In general, however, despite my critical reservations, I do still think that the exhibition can and will subtly facilitate the cultivation of both a more critical and a more openminded stance towards Mecca, Islam, and Muslims today, i.e. the cultivation of a “critical intimacy” to use Gayatri Spivak’s phrase. Whether and to what extent the desire for intimacy has indeed overruled the critical impetus in Longing for Mecca and other similar exhibitions is a topic that should be continued to be discussed in the future.

Pooyan Tamimi Arab

22 February, 2019, Amsterdam