Johanneke Kroesbergen-Kamps

The first cases of COVID-19 in Zambia appeared on March 19, 2020. Since then, 74 infections have been confirmed and there have been three deaths. Since the emergence of the first cases, the Zambian government has put in place relatively strict measures to curb the spread of the virus.[1] There is no complete lockdown, but people are strongly advised to stay at home, avoid unnecessary travel and adhere to social distancing. Schools and universities are closed, and gatherings of more than 50 people are prohibited. Street vending, an important part of the informal economy, is discouraged and in some cases forcibly restrained.

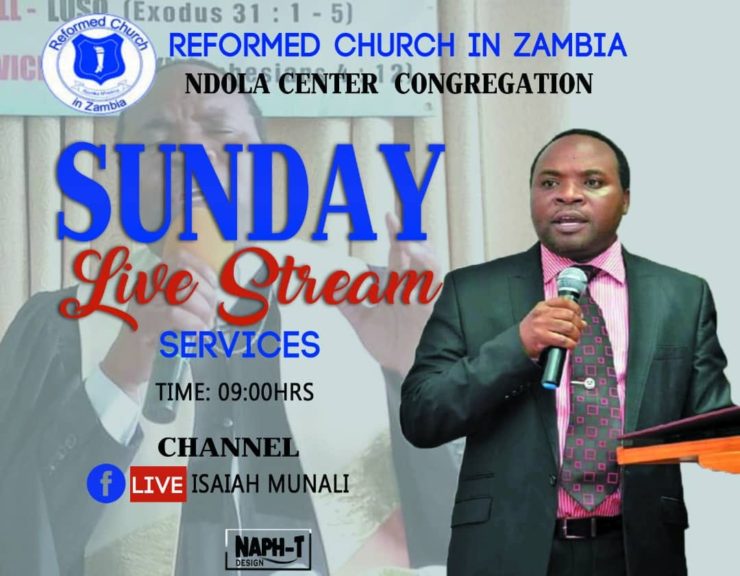

The Zambian government has not forbidden church services, although services are not allowed to take longer than one hour, and should be visited by less than 50 people who can keep social distance. Unlike the government, the main church mother bodies like the Council of Churches in Zambia and the Catholic Bishops Conference have advised their affiliated churches to halt worship services. One of Zambia’s mainline churches, the Reformed Church in Zambia (RCZ), has ordered its congregations not to come together in church, but to find other ways to keep in touch with congregations, such as through Facebook or WhatsApp groups.

This new situation poses a challenge to pastors all over Zambia. How to mediate the presence of God online, without a congregation? TV pastors like the famous Nigerian pastor TB Joshua have big audiences, so keeping an audience that is not bodily present must be possible. But the sermons of these television pastors are recorded in front of a live audience, with a camera switching strategically from the pastor on the stage to the emotional responses of the audience. These services further offer not just praise, worship, and a sermon but often testimonies of God’s power as well. All of this together tells the audience watching that something is really happening in that place: God is present.[2]

Live-streaming in times of corona is different, and for many pastors in the RCZ it is a learning process. I base these observations on Zambian online services on the first service that had to be presented without a congregation present, on Sunday 29 March 2020. I have watched 15 services posted on that day, mainly held from urban congregations and without exception by male pastors. In later weeks, more and more pastors have joined in posting their services on Facebook or YouTube. This piece, however, only looks at the first services and focuses on the setting of the service.

In some churches the pastor is flanked by members of a choir, standing at an appropriate distance. In others, the focus is on the pastor behind the lectern, on the pulpit or behind the altar, but a few members of the congregation can be heard. In these cases, songs can be sung and this makes the service more like an ordinary service. Yet, some forms of liturgy are hard to convey online. In recent years, worship in the RCZ has taken on evangelical and Pentecostal features. For example, one of the liturgies in the RCZ includes so-called mass prayer, in which the pastor gives a few prayer points for which each member can individually pray aloud. In a church with a pastor and only a skeleton crew, this doesn’t work – it is the pastor who is doing the prayer instead of the congregation.

Most online services are in English, sometimes going back and forth between English and one or even two vernaculars. The RCZ came into Zambia in the 19th century from the southeastern part of Zambia, where chiChewa is the main language. Even though the church now has a countrywide presence, chiChewa and its simplified version chiNyanja are still the main languages in the RCZ. On the congregations on the Copperbelt, chiBemba is spoken as well. In ordinary times, most congregations have an English service and a vernacular service in one week, and a combined service in which parts of the service are in English and parts in vernacular the other week. Many online services are in English, some combine English with a little explanation in the vernacular. The predominance of English in these online services is probably related to the audience of the service: people who have access to smartphones. Smartphones are the province of the young, for whom English is the language of the world and progress; and of the well-to-do, who will often use English in their jobs.

Most pastors choose a minimal service, with prayer, scripture reading, and a sermon, but without singing praise and worship. This seems a going back to the traditional Reformed style of an emphasis on the importance of the scripture. The thing that people go to church for, is the assumption, is the word of God. This is a valid Reformed point of view, fitting with a view on religion as an inward phenomenon. It is however also one that has become more and more outdated within the RCZ because of the recent shift to more evangelical and Pentecostal styles of worship, for which there is an increasing amount of attention in scholarly literature as well.[3] Therefore this format of online services can well be perceived as a step back by their audiences who have come to enjoy exuberant worship and a direct connection with God in mass prayer.

In all the online services, immediacy is preferred. In my own church, a South African Dutch Reformed congregation, pastors record the service a few days prior so that music or songs with texts can be edited in. The online services of the Reformed Church, by contrast, are almost exclusively life-streams, recorded, and broadcast immediately through Facebook. Although in the mostly minimalist services there is no singing or music that an audience can participate in, the comments on the posts “I am watching now,” “This is powerful,” “We are with you,” give a sense of an immediate community.

In only a limited number of services the audience was slightly bigger and more involved. When the pastor announced a time of mass prayer, the other people present started praying aloud as well; although the voice of the pastor was still the main anchor point. His shouted prayers against the demon of the coronavirus spiritualized the issue of the pandemic, which can have adverse effects on the community’s response to the virus, as has been argued by Damaris Parsitau[4] and Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu.[5] On the other hand, his performance showed clearly the image of the fighting man of God, involved in spiritual warfare between good and evil. This element of neo-Pentecostal theology makes the immediacy of both God and the forces of evil present to an audience. This pastor at least was fighting for his congregants, instead of merely trying to soothe them with words. In the popular shift towards Pentecostalism within the RCZ, this seems to be an element that is appreciated by audiences, and which is missing from the minimalist services of the more Reformed pastors.

While making God present via online services is already a challenge in urban areas, where most families have access to at least one smartphone where they can follow an online service, it is even more difficult in rural and peri-urban areas. Why post a service online if only a handful of congregants will be able to follow it? In fact, it is often not even possible to post a service online with the patchy network connections in rural areas. How pastors in these congregations will be able to encourage and keep their flock together is an altogether different question.

In many African churches, the mediation of God is achieved by showing signs of his presence. In the minimalistic Reformed-style services the presence of God is symbolized by his word. The popularity of evangelical-style praise and worship services and of testimonies in deliverance services shows that audiences often expect more than just such a minimal symbolic presence of God. In times of COVID-19, people all the more long for signs and experiences and an emotional connection to the presence of the divine. And yet, the shift to online worship poses a great challenge, even more so in rural areas, to fulfill their needs.

At the moment, online services are the way to go for a church like the RCZ. The services seem to connect communities when social distancing makes this impossible. Audiences know to find the live streams of their pastors, and pastors may even gain a greater reach because believers from other places in Zambia and even from other countries now have the opportunity to tune in. On the other side, the solution of online services is still very much a work in progress in which the main questions are how to mediate the presence of God in a minimalist, sterilized service without an audience to empathize with, and how to reach the people in rural areas who do not have access to online services. Creative solutions are called for to make online services a successful mass movement.

Johanneke Kroesbergen-Kamps is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Pretoria, where she investigates the religious identity of young pastors in the RCZ in a time where Reformed and Pentecostal theology are battling for dominance within the church. She organizes the blog Imagine Africa.

References

[1] This is the latest address held on 10 April, 2020 by Republican President Edgar Lungu detailing the government measures (link).

[2] See for a comprehensive argument about mediation and presence in televised religion Marleen de Witte’s Spirit Media. Charismatics, traditionalists and mediation practices in Ghana (2008).

[3] As an introduction I’ll just refer to Birgit Meyer’s inaugural address Mediation and the Genesis of Presence: Towards a Material Approach to Religion (2012).

[4] The Elephant Info, ”Religion in the age of Coronavirus” (link).

[5] J. Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu PhD, ”Dealing with a Spiritual Virus: Whither the Prophetic?” (link, Religious Matters, 2020).

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.