Photograph 1: Raum der Erinnerung im Grassi Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig. © Quelle: André Kempner, Leipziger Volkszeitung.

Museums house skeletal remains of all sorts. Catholic relics, for example, are sometimes exhibited, one such location being the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. In the 2022 article “Lonely Bones: Relics sans reliquaries”, Swedish art historian Lena Liepe states, “more than anything else, the exhibit of a skeletal fragment in a display case, as a thing among other things, is a testimony to the museum as an apparatus of modernity, with disenchantment, in the tradition of the Enlightenment, as one of its main missions.” In other words, museums are different from, for example, churches, in that museums can exhibit human remains in a secular framework.

The GRASSI Museum for Ethnology in Leipzig, Germany, however, does not exhibit skeletal remains as a “thing among other things”; the museum does not exhibit remains at all. In late 2021, the GRASSI Museum’s curators created a space in their newly finished Room of Remembering (shown above) that supports spiritual and religious activity involved in the return of human remains. This process, called repatriation, describes the return of human remains to people whose ancestors were stolen during the colonial period. The process of repatriation often involves a ceremonial aspect, as the remains are considered spiritually or religiously connected to descendants or those culturally affiliated.

Following Liepe’s statement, is the GRASSI Museum still an “apparatus of modernity”, an institution characterized by “disenchantment”, if it does not exhibit human remains and instead, creates a space for reburial rituals and spiritual activity? Is this museum (still) secular?

Such a question is misleading. The project “Multiple Secularities: Beyond the West, Beyond Modernity” at Leipzig University understands secularity as a function of differentiation on an actor level, in which people make distinctions between what is secular and what is religious through various media, including space and objects. Rather than insist on the secularity of an institution, it is perhaps more fruitful to ask what boundaries staff and visiting researchers draw with exhibition curation, architecture, language, and administration to limit or encourage certain behavior and speech, some of which are characterized as religious or secular.

As one of the participating former curators of this space in the GRASSI Museum in my role as research assistant between 2019-2021, I can offer a brief guide to the exhibition and ritual space in conjunction with some of the discussions from the curation team. The space analyzed in this post consists of an entry sign, the exhibition area, and the Room of Remembering. How the religious matter in each of these museum spaces affects visitors and claimants will only become clearer with its ongoing use, but a few preliminary observations can be made a year after its opening in 2022. With this post, I intend to render visible the religious matter in this space. Where matter is defined as religious “matters”, to emphasize the double meaning, in that identifying where religion is marked with material, the boundaries to the secular become refined. Objects next to each other are not mere things among things, rather, their curation is a source of boundary-making.

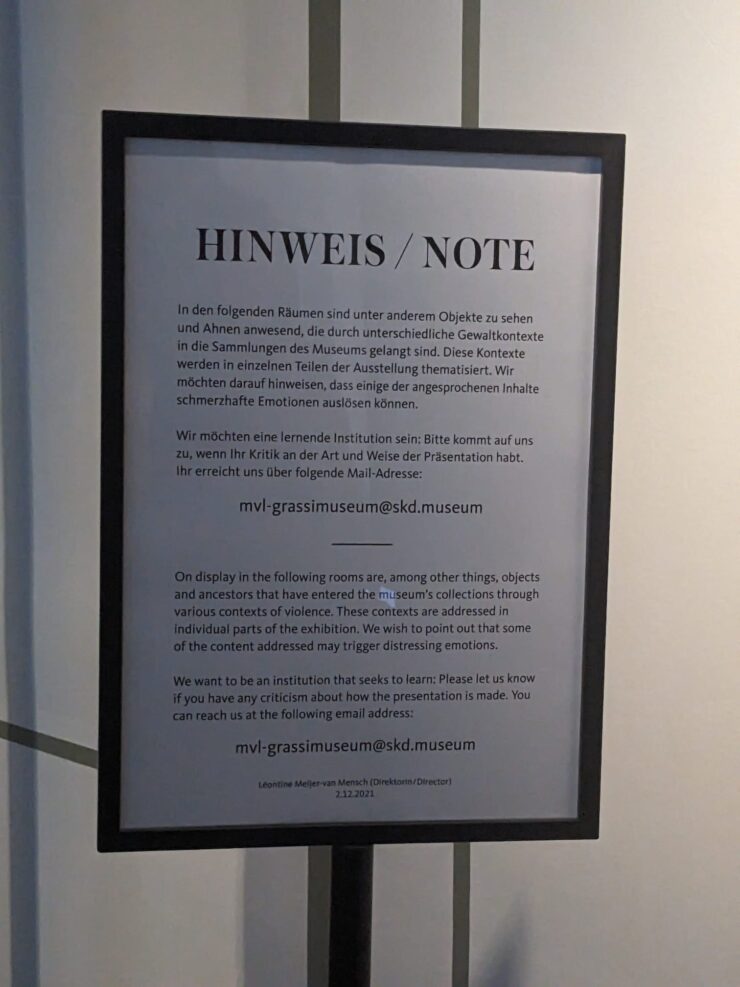

Visitors first encounter a sign before they enter the exhibition hall. The message states that ancestors are present, some acquired through violent acts, and that in this room, emotions may run high. The choice of the word “ancestors” is significant. Many institutions wrangle with appropriate language of descendants and human remains. Examples include the terms “remains,” “human remains,” “Ancestors” (sometimes lowercase), “Old People,” (similarly indeterminate capitalization) or simply “skulls”, “skeletons”, and “hair samples”. By utilizing the ancestor language of many descendant actors, the museum aligns its positionality with those impacted. Furthermore, the term “ancestors” draws singular, ahistorical “remains” into a relationship to claimants, a discourse of connection and permanence. The term “ancestor” transcends a local relationship into one in a broader frame of history or spiritual connotation. The placement of the sign at the beginning sets the positionality and further attaches a specific emotional tone for the coming areas.

Photograph 2: Sign upon entering the repatriation hall, also called the Room of Remembering. Photograph by author.

After passing the sign, the exhibition area offers educational opportunities for visitors unfamiliar with the complexities of repatriation. The photograph here illustrates that exhibition area from the perspective of a visitor standing at the far portal on the left in the first image (where the red and black photographs are framed) and looking back to where s/he came. It consists of three vitrine clusters that cycle through stories of current and past restitution and repatriation cases and provenance (more information about current and past repatriations should be found on the museum’s website, which has unfortunately not been updated since my departure in 2021). The vitrines are bound to change by the time readers of this post enter the space themselves, should they visit. For one example, the objects in the second vitrine shown in Photograph 3 have recently been restituted to Kaurna Country (near Adelaide) in Australia.

Photograph 3: Repatriation exhibition in 2023. Photograph by author.

Contemporary art and artifacts feature prominently here. These artists created the works either as recipients of restitution or commentators on the process. On this spiritually and emotionally sensitive topic, contemporary and sometimes abstract art forms are meant to offer artists not only a space to comment on their own restitution experiences but also for audiences to take a quiet moment for reflection. Reverence in art spaces has been readily analyzed, for example in Civilizing Rituals (1995), where Carol Duncan reminds us of the “liminality” of art museums, a term borrowed from Victor Turner to describe the in-between state before and after a transformative experience, something he theorizes as characteristic of rituals. Duncan’s rituals are pious, reduced, and inward, something I read as specifically Protestant. Duncan’s analysis applied to this exhibition shows, first, how non-repatriation claimant visitors and claimant visitors alike participate in ritual activity in an exhibition and second, how contemporary art as a material aid in evoking piety contributes to the goal of an emotional transformation in the educational space of the exhibition.

After walking through the ethnographically and emotionally informative exhibition, visitors can enter a space to the right of the exhibition called the Room of Remembering (the main entrance shown in Photograph 4). For those who are professionals in the field, both out of cultural obligation or moral inclination, this space offers an area to practice repatriation rituals and protocols. Photographs and videos of previous ritual practices are on display for visitors, yet sometimes such rituals or cultural activities are subject to privacy per the wishes of those taking part. The curators and architects of the space prioritized the religious and cultural perspectives of descendants of the remains or people who are culturally affiliated with them. Visitors without such a connection are nonetheless introduced to the topic but with special attention to cultural and emotional tone.

The Room of Remembering is sectioned off through spatial and visual cues. Spatially, four large wooden panels act as walls that can be opened or closed depending on whether or not people conduct ritual activity in the space. Open, the room acts as an additional exhibition space. Objects used in ritual activity as well as photos of repatriations in that space (as well as the courtyard below) are on display. We designed the space also to offer educational events for the public on repatriation and restitution. For example, in November 2022, the museum hosted an open panel discussion with representatives from Awabakal, Gannagal, Mutthi Mutthi, and Worimi Nations. When the space is closed, however, the walls block visual access to the room, and access is granted only to descendants and their delegations.

Visitors are visually invited into the different museum territory by the color of the walls. In the repatriation space, the clinical white walls of the exhibition space in the exhibition space turn a sandy ochre. The color does not serve to represent all regions to which repatriations will part, rather, it intends to reflect a different atmosphere than that conveyed by a white exhibition wall or a dark museum corridor. The color of the wall contributes to the emotional experience of the room, taking into account the different symbolic weights of varying colors in the funeral rituals of different cultures. Even the walls of the forensic research room and the new depot for remains (closed to visitors) are painted ochre. Our decision was intended to encourage a more sensitive approach to the subject matter of human remains, to be researched not as scientific specimens or viewed as objects of art or science but as individuals with a biography.

Photograph 4: Ritual objects in the Room of Remembering. Photograph by author, 2023.

Alongside the color of the walls, the space is decorated primarily with Aboriginal Australian objects and color schemes. Indeed, curators argued over the various associations between color, feeling, and religious or cultural symbols. Many of the first repatriations from the Sächsische Ethnographische Sammlungen (SES) have indeed gone to Australia; however, other groups of people with different cultural and religious symbols will soon receive remains and objects. Time will tell how this space will develop and perhaps depart from an Aboriginal Australian focus as other regions gain prominence in SES repatriation activities.

Although visitors related to ancestors held in the wider museum complex of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden are certainly in the minority of yearly visitors to the GRASSI Museum, we curated this ritual space with the intention of making culturally diverse ritual activity more accessible to those populations. We intended the space to appear welcoming by using natural light. Windows can be opened to clear the air after smoking ceremonies. Vitrines, as visual markers for museums, are minimal and during rituals, moved outside of the ritual space. For that matter, the only objects on display in this vicinity are either on their way to being restituted or have recently been used to tell the stories of repatriations past. Museum staff, curators, and architects, myself included, aimed to design a space where ritual activity is neither ignored nor tolerated but rather is encouraged, despite the fact that those practicing the rituals may only visit the museum every few years, or even only once.

Visual and spatial materials separate two spaces, tangible borders in a differentiation process. The walls and wall colors mark boundaries between two ritual spaces, one an exhibition space, which includes the rituals of art museums, and the other for repatriation rituals. The history of museums as secular institutions certainly influences their curation, administration, and storage areas in the present. However, rather than simply claim them as secular spaces, art historians, museum studies scholars, and religious studies scholars should look at the differentiation- and boundary-making processes between secular and religious to support or complicate that frame. What exactly makes a museum secular, how can we tell it is such, and what purpose does that secularity serve? Indeed, the museum staff are very aware of these questions. In a previous exhibition (Werkstatt: PROLOGUE), curators asked, “how does a museum change the status of things?” concerning objects used for religious practices now held in museum function, and “how do museum actors determine the way an object is perceived” by visitors?

Differentiation processes along secular-religious boundaries are tangible in museum spaces where objects and spaces oscillate between sites of secular and religious activity. Some assume that museums cultivate the secular, and consequently, that their visitors may understand them as rational and unemotional institutions. Acknowledging the history of museums as public secular institutions, I nonetheless do not assume that the museum can be pinned down to being a singularly secular place, let alone one that is unemotional or objective. Museums harbor power both by object possession and representation. Rather than consider museums as simply secular spaces, museums and “their” “things” can be seen as settings with individual circuits between religion and non-religion with their own ranges of emotional intention and expression.

Works cited:

Dehail, Judith. “Secular Objects and Bodily Affects in the Museum” in Monique Scheer, Nadia Fadil, and Birgitte Schepelern Johansen, eds. Secular Bodies, Affects, and Emotions: European Configurations. 1 ed. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), p. 61–73.

Fforde, Cressida, Jilda Andrews, Edward Halealoha Ayau, Laurajane Smith, and Paul Turnbull. “Emotion and the Return of Ancestors: Repatriation as Affective Practice” in Alice Stevenson, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Museum Archeology, (Oxford: Oxford Academic, 2022), p. 65–84.

Johnson, Greg. “Naturally There: Discourses of Permanence in the Repatriation Context.” History of Religions 44, no. 1 (2004). p. 38.

Liepe, Lena, “Lonely Bones: Relics sans reliquaries” in Fricke, Beate, and Aden Kumler, eds. Destroyed–Disappeared–Lost–Never Were. ICMA Books: Viewpoints. (University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2022). p. 108.

Miriam C. Hamburger received her M.A. in Religious Studies from Leipzig University and her B.A. in Religious Studies and Art History from Occidental College (Los Angeles, CA). At the GRASSI Museum for Ethnology in Leipzig, she worked in object conversation, research, and supported cases of repatriation and restitution (2017-2022). She is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Religious Studies and Native Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. See one of her recent publications here.