Of Pandemics and Passions: Virtual Choirs and Collective Healings

Ernst van den Hemel (Meertens Institute)

A surprising amount of passion plays originated as a reaction to the outbreak of infectious diseases. Take, for instance, one of the world’s most well-known passion plays: those of the Bavarian village Oberammergau. When, in 1633, the plague was ravaging the European continent, a pledge was made. If the villagers would be spared, a passion play would be staged every ten years. Legend has it not a single villager died of the plague after the pledge was made. The village of Oberammergau has organized the passion play continuously every ten years since then, making it the longest lasting tradition of passion plays in the world.

Illustration 1: Passion Play of Oberammergau, 1922.

Another example is the passion play of Iztapalapa in Mexico. In 1843, in the midst of an outbreak of cholera, the villagers started a procession. When the epidemic ended, it was seen as a miracle, and the tradition has grown into a yearly spectacle involving up to 5000 actors, and millions of visitors.

These passion plays are not just attempts to implore divine powers to spare lives, they are also, or perhaps predominantly, ritualized and heritagized moments in which comforting emotions are evoked and shared in a community. As I will show, it is this public performance of collective emotion which has made passion plays a successful genre in 21st century Dutch society, even or perhaps because of continuous reports of secularization. This particular popularity of passion plays, in turn, explains how during the current Corona endemic passion plays take on new relevance and ritualized forms. But first, what makes Easter such a suitable moment for passionate spectacle?

Easter as public healing

It is no coincidence that Easter is the holiday for collective spectacles. Perhaps as no other moment in the Christian calendar, Easter is associated with multimedial performances of the basic narrative of Christianity. Already in the fourth century, for instance, we see that the narrative of Christ’s suffering is sung during services surrounding Easter with a certain theatricality. In later centuries this evolved into more elaborate performances including the multimedial staging of passion plays in the Middle Ages. Bach’s Saint Matthew’s Passion can be seen as part of this tradition to musically present the story of Christ’s suffering and resurrection in the Holy Week. Frequently, these performances take on significance beyond the walls of the church. Passion plays are performed in public spaces and Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion (as well as other passion compositions) are performed in concert halls and consumed in many different contexts outside of liturgy. In short, Easter becomes a moment in the religious calendar during which mediatized public emotions take center stage.

A good example of this is how the village of Walsham in Suffolk, England reacted to the threat of the plague in 1348. Walsham provides an unusually well-documented example of a community’s reaction to the plague. John Hatcher wrote a fictionalized account of Walsham during the plague entitled ‘The Black Death: an Intimate History’ in which he outlines how the plague reaches Walsham right before Easter. The villagers, who had been bunkered down already in anxious expectation of things to come, now saw themselves confronted with the first casualties. Easter was in this setting not just a time for introspection and prayer but also for public desire of comfort and cohesion. The packed churches and bustling processions, though they most likely did not do much good to stem the infection rate, show how Easter is a time in which mediatized performances of Christ’s suffering can be used by suffering communities.

Passion Plays in 21st-century Netherlands

This history, in which passion plays are seen as beneficial for communities in times of anguish and affliction, is of help to understand the perhaps surprising popularity of passion plays in the Netherlands. The 21st century saw a remarkable rise in popularity of passion plays. Once deemed old-fashioned, existing passion plays saw a rise in numbers of visitors and new passion plays generated an audience of millions in the Netherlands.

Take for instance the passion play of Hertme. Hertme was, from 1953 until the mid-sixties, the site for a passion play. The tradition was cancelled because of diminishing interest. In 2011, however, Hertme organized a reboot of the tradition, generating both public interest and cultural appreciation in the process. The organizers highlighted not just the religious dimension of the passion play, but rather its desires positive effect on a society which has forgotten what binds it together.

Illustration 2: Photograph taken during The Passion Play of Hertme, 2019.

A second example also originated in the year 2011. This year saw the Dutch premiere of The Passion, a televised multimedial spectacle. This modernized passion play, including a procession with a big neon cross, biblical characters singing contemporary pop songs and a virtual procession in which people can participate through social media, draws an annual audience of about three million viewers. The organizers highlight the importance of the passion narrative for contemporary Dutch society, and they explicitly reference feelings of loneliness, lack of social cohesion and general direction in life. The Passion, so state the organizers, is able to address a variety of contemporary concerns and to provide a platform to live through these emotions collectively.

Illustration 3: The Passion, photograph taken by Ernst van den Hemel

As a third example, we can look at the Dutch tradition of performing Bach’s Saint Matthew’s Passion. In my book I have provided argumentation on why we can see this as a continuation of medieval passion plays, but let me limit myself here to highlight how also in this performance of the passion narrative, people attribute healing qualities to the passion. Listening to Saint Matthew’s Passion is frequently described, also by staunch atheists, as an experience of comfort in worrying times. To name just one example, here is how prime minister Mark Rutte speaks of his visits to the Saint Matthew’s Passion:

”There is no music with greater emotional depth. (…) As prime minister, I get to go to see the Saint Matthew’s Passion every year. That’s a tradition in the Netherlands. You sit there for three hours and you are washed away by waves of the most divine music imagineable. (…) When you listen to Bach, you know, I think even when you see all the misery in the world all the horrors and wars, we are also capable of the highest good.”

Passion plays in endemic times

Although the medically curative elements are no longer dominant, the aspect of collective, cultural healing seems to be a core ingredient in the popularity of contemporary passion plays in the Netherlands. Commentators as Willem Schinkel have described contemporary Dutch society as increasingly concerned with what he calls ‘social hypochondria’. A variety of developments like migration, globalization and individualism are experienced as illnesses of society. Against this backdrop, issues of religious-cultural identity take on new relevance. Passion plays are seen as antidotes to a variety of ailments of contemporary Dutch society.

This is also clear from the way in which passion plays are staged during our present day epidemic. Far from being only a religious or musical spectacle which can be rescheduled, it becomes clear that the passion plays attempt to fulfil a ritual role. To illustrate this point, let me provide a selection of Dutch passion plays during Corona (this list doubles as a somewhat unorthodox cultural agenda of passion in contemporary Dutch society):

– Virtual Sing-Along Saint Matthew’s Passion

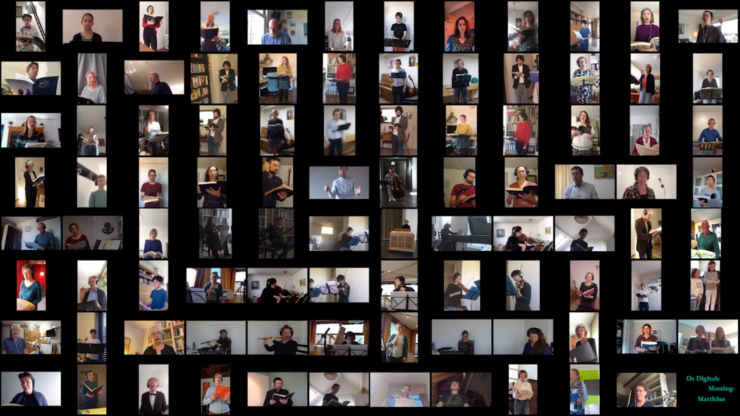

The foundation Passieprojecten (‘Passion projects) co-organizes a virtual sing-along-Saint-Matthew’s Passion. This allows people to record themselves singing the Saint Matthew’s Passion. The organizers collect these videos and edit them so that a virtual choir comes into being. The result can be seen here.

Illustration 4: screenshot of the digital sing-along Saint Matthew’s Passion.

– This year, The Passion was cancelled. Instead of the usual and the organizers have broadcasted a combination of a best-of selection of highlights from previous years and an increased emphasis on the virtual procession. People share testimonials in an online setting. The Passion 2020 concluded with a montage of a Dutch pop-song ‘Geef Mij Nu Je Angst’ (‘Give me your fear’) which was sung by a combination of Dutch celebrities, supermarket employees, health-care workers and ordinary Dutch people. The result was a virtual choir of participants who, in their diversity, are meant to simultaneously represent and comfort afflicted Dutch society (click here to watch).

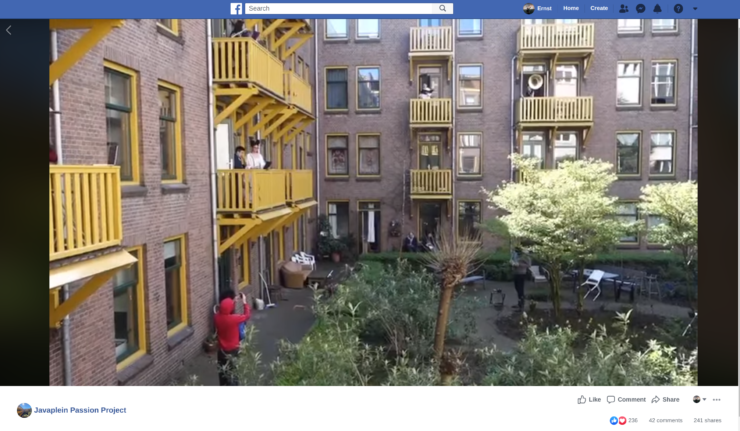

– The ‘Javaplein Passion Project’ is an initiative of students of the Amsterdam conservatory. In isolation they have taken it upon themselves to perform parts of passion composition from their balconies. This way they fuse two rituals: one is the annual performance of passion compositions, the other – of a more recent date is- the ritual of performing music from balconies in order to express and experience a sense of togetherness in times of quarantine and social isolation.

(Illustration 5: screenshot of the facebookpage of the Javaplein Passion Project)

All in all, our afflicted present shows how the curative elements of passion plays take on new life in the 21st century. It also shows how these contemporary exceptional circumstances provide both a reboot as well as an innovation of ritual.

Ernst van den Hemel (1981) is a scholar of religious studies and literature. He is a researcher at the Meertens institute, where he works on a new research project on populism, religion and social media (click here). His book Passie voor de Passie. De Matthäus, The Passion en andere passiespelen in ontkerkelijkt Nederland (Utrecht: Ten Have, 2020), appeared this month as the new-year-book of the Meertens institute (link). This publication was written as part of the HERA research project HERILIGION (link).

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.