Natalie Lang

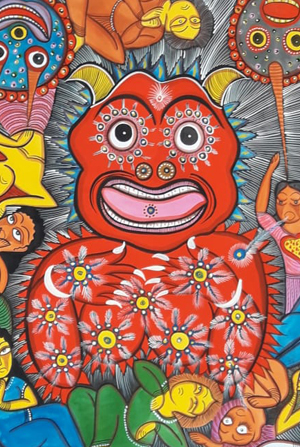

When the world came to a halt in many places because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and researchers were worried about their fieldwork trips and research plans, Carola Lorea convinced her colleagues at the Religion and Globalisation Cluster at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, to come together to react to these frightening circumstances by researching and documenting religious responses to the pandemic. Inspired by the creative ways in which people in Mumbai and scroll-painters in Bengal represented the coronavirus in the form of a demon (asur), we decided to launch the research blog CoronAsur (Carola Lorea’s introduction to the blog).

The Blog as a Method

As fieldwork possibilities are limited and conferences are cancelled or shifted to the online world, our blog provides a platform to collect ethnographic material about religion and COVID-19, and to discuss the methodological and theoretical implications that the pandemic has for research on religion. We conceive CoronAsur as a platform for discussion that seeks to go beyond merely addressing an academic elite by also inviting young career scholars, religious practitioners and activists to contribute, and by publishing ethnographic observations even before they have been developed into complex theoretical statements. We believe that, in such a rendering, the blog will become an accessible archive of multiple observations on religious practices during the pandemic. We hope that this will provide a helpful resource for future research on religion, especially in times of crisis. In the following, we provide glimpses into the first thirty contributions.

Asian and Global Perspectives

When the Jade Emperor asks in a joking meme by the Taiwanese author Banaishunzi why the Four-faced Buddha does not attend the “Heavenly Pandemic Prevention Meeting”, the Gods answer: “He is short of a mask, since we are only allowed to redeem three pieces per week!” (Dean Wang on religious humor during the pandemic).

Not only do our blog posts give insights into jokes from different Asian traditions, settings, and languages in English; we also publish translated pieces from Asian languages for contributors who do not write in English. While grounded in observations about religious phenomena in Asia, the contributions reach across religious traditions, spiritual practices, and continents, and highlight the global dimensions of COVID-19 related religious changes.

Blog entries also deal with methodological questions about how to do research under these conditions. Approaches include creating Facebook pages and story repositories as part of digital ethnography (Lynn Wong), as well as participatory auto-ethnography within one’s family network (Yasmeen Arif on messages on social media during Ramadan).

Religion, Media, and the Senses

Although scholars have suggested that religion always entails mediation or is itself mediation, and although religion has been mediated through new media long before this pandemic, the scale and the use of such media has increased and become key to ritual innovations in corona times. Among the first posts, Nan Ouyang shares how a Buddhist monastery in China has circulated via WeChat a guide for “online merit fields” where devotees can choose different offering and donation services. Online ritual options have also attracted increased attention among Buddhists in Singapore since the implementation of social distancing measures. In addition to possibilities of bathing the Buddha online, and online ancestor worship through purchasable ancestor praying packages, the act of liking and sharing Buddhist webpages becomes a way to celebrate Vesak Day in Singapore (Jack Chia, Ying Ruo Show). The Philippine Catholic Church uses “liturgical televisuality” to create “a narrative of encounter, despite physical distancing” (Louie Jon A. Sánchez). While appearing as innovative, major denominations are often opposed to innovation and instead reproduce conservative views on religious authority when going digital (Bernardo Brown).

Questions about the efficacy of virtual rituals are largely answered positively, as deities and ancestors that are prayed to without the usual ritual materials will understand the special circumstances, and ritual traditions have always been in flux. However, online religion is often perceived as disembodying or at least limiting the sensory experience of religious practice and as an interim solution alone (Koh Keng We, Ke Hong Lim, and Esmond Soh on Chinese religious and spiritual practices in Singapore, Natalie Lang on Hindus in Singapore). Rather than the global lockdown leading to diminished and dis-embodied spirituality, the rise in downloads of meditation apps during confinement reveals the importance of spiritual practices for the confined body-mind complex even beyond mainstream definitions of religion (Carola Lorea).

Online and Domestic Religion

When religion goes online, it feels particularly precious to get glimpses of how people practice religion in their homes. A Singaporean Methodist Church encouraged online “worshippers to dress in their Sunday best, switch mobile phones to silent mode, and physically participate as instructed during the service (e.g., rise to sing, close eyes to say prayers, read up during scripture response) even if alone at home” (Lynn Wong). Among the most creative innovations documented on this blog are the homely mini-mosques built for Ramadan and Eid celebrations (Faizah Zakaria).

Rather than suggesting that religious practices become increasingly private, individual affairs, the interrelations between private and public aspects of online mediated religious experiences are complex. For instance, the gaze of the still camera renders gestures of praying public and at once allows for intimate worship (Alvin Lim).

It is difficult yet interesting to know how gendered religious roles are re-negotiated when religious practices are reduced to people’s homes (Nurul Fadiah Johari on Malay Muslims). It also becomes methodologically challenging to trace how religious contents move through share buttons and advertisement algorithms and what power relations are involved when religion goes online in such accelerated and larger scale (Faizah Zakaria).

Religion and Charity

Smaller religious institutions, particularly those which do not necessarily have the capacity to quickly transfer their services and donation systems to the online world, struggle with the sudden lack of donations to pay their lease (Ying Ruo Show on Chinese temples in Singapore). Some religious educational institutions have probably not been affected financially to this extent since World War II (Ji Yun on the Buddhist College of Singapore). Businesses that usually cater ritual offerings, foods, and other infrastructure for religious gatherings are equally affected (Victor Yue).

At the same time, some examples seem to suggest an increased willingness to donate related to the current conditions. Muslim reactions in Indonesia include a widespread use of online almsgiving (zakat) apps (Amelia Fauzia). Acts of generosity also include religious organizations becoming home to the homeless or providing food for migrant workers, which in turn also contributes to their visibility as important actors of ‘secular’ civil society (Malini Bhattacharjee on Hindu nationalist groups in India, Lee Soo Ann on the Bible Society of Singapore).

Prayer and Social Distancing

Before places of worship in many corners of the world had to completely reduce their communication with devotees to online media, innovations were quickly being developed to continue forms of congregation and ritual, including socially distanced prayer. Lingji meditation by sitting in a circle of offerings that allows social distancing has received increased attention in Taiwan in the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, even though Taiwan’s infection rate was low (Fabian Graham). When several thousand devotees did not respect social distancing when worshipping the goddess Mazu during her annual procession in Taiwan, which was postponed for a second time in history due to a pandemic, devotees believed that Mazu protected them from an outbreak (Peng Chew Lim and Hsun Chang).

Religion and Disease

In addition to innovations of ritual acts, venerated entities themselves are also newly imagined, as observed in the recent veneration of Saint Corona in relation to the virus, as well as in new Hindu divine and demonic forms of the virus (Natalie Lang). Extensive use of sacred plants in South India, which go as far as wearing masks made of neem leaves instead of surgical masks, illustrates the important connection between disease and sacred power, and a shared repertoire of medicinal and ritual substances (Indira Arumugam). Plants, animals, and food habits are important in many religious traditions’ framings of disease. As several groups link the consumption of meat with the pandemic, initiatives also include promoting vegetarianism through sharing cooking recipes (Shen Yeh-Ying on Yiguandao in Taiwan).

Where Corona Leads Us

Since the creation of CoronAsur in May 2020, we have learned enormously from the diverse contributions to the blog. Long-term research will provide valuable insights into the dynamic interactions of religion and society in times of crisis. We are enthusiastic about the conversations around religion and COVID-19 that we have initiated and we look forward to continuing these here (submission guidelines).

Natalie Lang is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.