David Morgan

“All my humor is based on destruction and despair. If the whole world were tranquil, I’d be standing in the breadline—right in back of J. Edgar Hoover.”

-Lenny Bruce

“Humor is just another defense against the universe.”

-Mel Brooks

On the evidence of what Lenny Bruce and Mel Brooks proclaim, humor is mercifully entangled with disaster. Each comedian conveys the sentiment in broadly existential terms, but we may put the matter in equally apt political form: humor is a life line in dark, oppressive times because it deftly re-negotiates power relations. By speaking truth to power, by deriding those in power, by exposing their hypocrisy, by caricaturing their vanity, by spoofing sanctimoniousness or self-righteousness, different kinds of humor allow those who laugh an alternative to mere impotence. Everything may be going to hell in a handbasket, but at least we can step momentarily outside of the chaos by laughing about it.

One reason that humor provides this benefit is that those laughing discover they are not alone, but share the unfortunate state they are in and the heterotopia of humor. Humor offers a certain kind of transcendence from which to see things as they are and to do so in solidarity with those who are like-minded, which is better than being alone and nothing more than a victim of the situation. As a kind of truth-telling, humor as an edge that reality itself cannot blunt. Humor may not deliver a robust community, but it promises that one is there, waiting for the opportunity to emerge when the political tide shifts.

Religious people in pandemics are busy comforting the afflicted, praying for divine intervention, looking for means of miraculous deliverance, crafting theological explanations of why the evil is at work, and sometimes, the historical record shows, finding someone to blame for the mess. Religions also offer hope against the darkness of suffering and death. They offer community, counsel, compassion, and organized efforts at comfort and assistance. Religions offer a different perspective than abject victimhood.

But is religion funny? The wealth of religion jokes is clear evidence that many find it to be. But then, any human activity that takes itself seriously is not only liable to riposte and skewering—it needs the acerbic eye of comedy to keep it honest. I’d like to focus on three contemporary visual examples that circulate in the US, each of which shows a different genre of humor at work: irony, satire, and parody. Each captures a different way of regarding Christianity in the present pandemic.

Irony

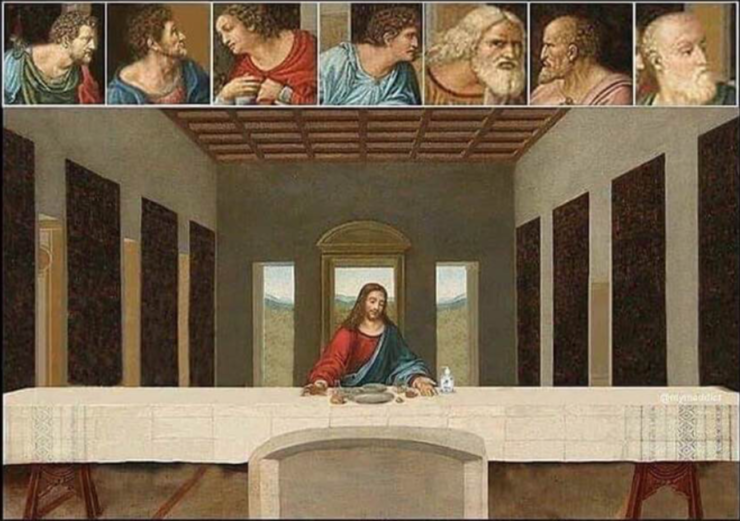

Social distancing is bothersome because it seems to sanction anti-social behavior. You find yourself doing what your parents taught you not to do in the encounter with others: hold them at a cool distance, walk around them, wave but do not shake their hands, don’t breathe the air they exhale, no touching of any kind, don’t embrace them or slap any shoulders. In religious worship services, it has long been common to do all of these as part of fellowship, the companionship of fellow worshipers. The Christian rite of Holy Communion means gathering in a group to receive the host handed out or placed in the communicant’s mouth by a priest or pastor. That contact is now understood to risk transmitting the coronavirus. So many Christians no longer gather to celebrate the sacrament. It is ironic that Jesus is understood to have offered his life as a sacrifice for humankind’s redemption, but the ritual that applies this to the community of believers has been temporarily suspended. The irony is captured very cleverly by the manipulation of Leonardo DaVinci’s iconic Last Supper in an image posted on St. Pixel’s FaceBook page (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Last Supper with Social Distancing, St. Pixels FaceBook page, https://www.facebook.com/stpixels/

Jesus has been left alone at the long table, his disciples having retreated to the safe distance from which they log on, hovering as insets in a Zoom session. The irony puns with a groan: the sacramental host has become the host of a virtual meeting. Jesus sits quietly, a bottle of hand sanitizer at this side, officiating like a priest at a barren altar. Even the Son of Man must sterilize his hands before offering his flesh for the redemption of humanity. The implications are portentous, though it is easy to overthink light humor. Perhaps it is no more than a fun gag, the pictorial equivalent of physical humor. Even the doorway later cut in the wall of the refectory that Leonardo’s mural decorates shows up in Figure 1, looming before the table for no particular reason—other than that it was there in the reproduction used by the image-maker to produce the humorous appropriation of Leonardo’s painting. The endless devotional reiterations of the image over the centuries have always made sure to eliminate the intrusion.

Or maybe there is more to consider—such as the irony that the sacrament is no longer a gathering of the faithful, but the desolate memory of an embodied practice commemorating the incarnation of the deity. Figure 1 could be taken to mourn the loss of something that lies at the heart of Christianity, something robbed by the pandemic. But the online mass is something that many families are turning to since parish churches locked their doors. Does virtual mass count as a sacrament? Catholic authorities ruled many years ago that televised or online mass does not fulfill the obligation to attend weekly mass. Nor does it offer the efficacy of the physical sacrament. As a group of bishops in Peru announced in 2005: “There are no sacraments on the Internet” (link). Yet the pressure of the coronavirus has already come to require some flexibility. According to the archdiocese of New York, remote access to the mass can occur as “an act of spiritual communion,” that is, as a communication of grace to the soul that longs for the Eucharist but is unable to be physically present for the rite (link). Virtual presence qualifies, at least extraordinarily, for real presence, though not as a full substitute.

Perhaps Pope Francis is nudging the Church in this direction with the austere magnificence of the live broadcast of his mass in an empty St. Peter’s Square on March 27. It was a remarkable crafting of spectacle—not vacuous showmanship, but poignant theater (see, for instance, “How the pope put ‘truth on display’ in an empty St. Peter’s Square,” link). The difference between Francis as impresario of absence and Jesus as lonely ritualist resides precisely in one’s response: Francis makes the mass itself lament the absent audience of participants. The transformation of Leonardo’s image may very well do the same, but with a smile—not of ridicule, but more like a burlesque pratfall. Yet the message in each case is comparable: this isn’t the way it is supposed to be, something vital is missing—the pious participant-viewer. The edge, if there is one, is that Christians have sacrificed communal ritual for personal safety. Who can blame them? And yet when an Italian priest declined the use of a ventilator so that it might be used by a younger victim of the virus, and shortly later died from his infection, there was something unmistakably Nazarene about the act.

Satire

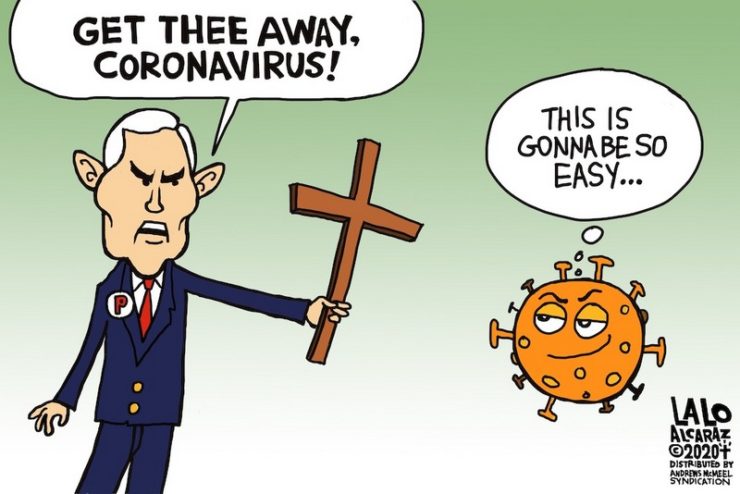

If the use of Leonardo’s mural and the flawless orchestration of Francis’ mass are images produced to endorse religious sentiment at a time of human travail, Figure 2 understands religion, in particular, Christianity, very differently. Posted on a humanist/atheist website that is operated by a former Evangelical pastor (link), the image pits a cross-wielding Vice President Mike Pence against a leering coronavirus. Pence, famous for his puritanical Evangelicalism, and named by President Trump to lead the White House pandemic task force, may stand in for his boss’ early reticence to take the viral menace seriously. But posted at the website it is, viewers won’t miss the image’s sharp swipe at religion as an ineffective way of fighting the pandemic. It satirizes not only Trump on political grounds, but Pence on religious. This is humor as critique, ham-fisted and bluntly ideological.

Fig. 2. Pence and Coronavirus, by Lalo Alcaraz, 2020

A tradition of freethinkers using cartoons to pommel religion in the United States goes back to the nineteenth century (see Leigh Schmidt, Village Atheists: How America’s Unbelievers Made Their Way in a Godly Nation, Princeton UP, 2006). It is a one-sided humor. Of course, humor is perhaps always more or less one-sided, its frisson coming at someone’s expense. But the political use of cartoons is always all about asserting boundaries. The point of such imagery is not to limn subtleties and nuances, but to distinguish in the boldest terms what separates those on the ‘right’ side from everyone on the other. Ridicule, as in Figure 2, is not meant to argue or persuade, but to deride by mockery. That is harsh, but social conflict is sometimes generated by real philosophical difference. The political aspect of Figure 2’s critique of the Trump administration’s early soft-peddling of the pandemic slides seamlessly into the humanist denunciation of Evangelicalism, which recalls Trump’s own sympathies for the anti-vaccination movement, which includes many conservative Protestants and Catholics. The laughter evoked by Figure 2 is not the self-effacing sort, but the polarizing kind, a laughing “at” meant to mobilize opinion. And it is conducted within the largely impervious mediated bubbles of elective affinity that dominate social media. If there are any Evangelicals following the humanist website that posted Figure 2, it is only as trolls.

Parody

If the irony of Figure 1 is religious groups scrutinizing the self-imposed contradictions of public safety efforts on religious fellowship and ritual life, and the satire of Figure 2 is humanist ridicule of religious response to the pandemic, Figure 3 presents a parody that spoofs a familiar visual motif and credulous viewers of it by substituting Dr. Anthony Fauci for the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Fig. 3. Dr Anthony Fauci as the Sacred Heart of Jesus

Religion and science get related in a variety of ways, but one of them is comfort, especially in a time like the present. People want to know this isn’t the end of the world, that the pandemic will end, that science will mercifully intervene with a vaccination. Science is modernity’s answer to disasters. More than government, more than religion, people expect something decisive from the folks in white lab coats. This is clear if we take the substitution of scientist for Jesus in this image to address the greater hope American’s pin on Fauci than on Trump, whose authority on public health withers beside Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the White House eminence grise on the pandemic. But that may be pushing it. The image may be neither critique nor lament, neither irony nor satire. Nor is it part of a Habermasian public sphere, waging a rational argument that might persuade viewers regarding some claim. Is there an argument at work in the image’s features? It seems to poke fun at the notion that religion and science combined are the greater prophylactic than either by itself.

The choice of a Sacred Heart candle is noteworthy. The image-maker did not choose an example of Jesus on the cross. That would have struck many as weird and others as sacrilegious. And it would risk miscommunication: Fauci is not suffering in any significant way. He is not Christ-like in that way. He is rather the reliable spokesman to whom the media (and therefore many of us) look for measured, scientifically grounded announcements on the progression of the disease and what to do about it. Given his new prominence in the public eye, it is also possible that the image was produced as a piece of satire mocking popular confidence in Fauci, who is viewed by many Trump supporters as untrustworthy, a wolf in sheep’s clothing, grazing in the West Wing.

But if we stay with the image as parody, the Sacred Heart motif may have been chosen for its connotation of the kind of religion that sits quaintly on a shelf, in the background of everyday life, where it provides comfort and assurance. The candle is a kind of night light, offering confidence to the child during the night. A reassuring shimmer that keeps the bogey man at bay. The comforting glow of this Sacred Heart of Science is a guiding light. It is the sort of message the general public might appreciate. But the use of the motif in Figure 3 may being using religion to parody a naïve exaltation of science.

But if that’s going too far, the image undeniably exhibits a high degree of visual craft. It elicited a double take when I first saw it. Perhaps the enchantment of the result lies mostly in the deft use of Photoshop to carry out the substitution. For a moment, it looks like the Sacred Heart. The well-executed technique fools the eye, if only for an instant. The quick discovery of the forgery is the point, the amusing jolt that evokes a laugh. This is a case in which the anthropologist Alfred Gell is right to argue that technological enchantment can produce a ‘wow’ that is enchanting.

The three instances of humor considered here set out to construct different views of religion in the public response to the pandemic. The irony of Figure 1 wryly notes the inversion of normal circumstances. Consider a dictionary definition of the term: irony is “the expression of one’s meaning by using language that normally signifies the opposite, typically for humorous or emphatic effect” (Lexico.com). The satire of Figure 2 derisively pits the weakness of religion and its political proponents against a grim adversary. Satire: “The use of humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and other topical issues”. And the parody of Figure 3 spoofs the viewer’s unrealistic expectations in a momentary deception. Parody: “An imitation of the style of a particular writer, artist, or genre with deliberate exaggeration for comic effect”. Three ways of thinking about religion in the time of pandemic: irony’s self-criticism of religion, satire’s mockery of it, and parody’s use of religion to unveil the naïve sacralization of science. Of course, such anatomizing comes at the expense of the humor itself, reminding us of what E. B. White wisely observed: “Analyzing humor is like dissecting a frog. Few people are interested and the frog dies of it.” That’s true enough, but discerning how humor about religion frames the perception of the pandemic is worth the frog.

David Morgan is professor of Religious Studies at Duke University.

Click here to read Birgit Meyer’s recent interview with David in the context of his recent visit to Utrecht.

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.