Johanneke Kroesbergen-Kamps & Hermen Kroesbergen

In Zambia, like in other African countries, the COVID-19 pandemic started very slowly, while the government was quick to take action. Even before the first Coronavirus case on Zambian soil was confirmed on 18 March 2020, hygiene measures were announced and all schools and universities were closed. A week later, after two people who had visited France tested positive on COVID-19, more measures were announced, including a ban on gatherings of more than 50 people. This was a sign for many churches, including the Reformed Church in Zambia (RCZ), to suspend their worship services and other activities like camps, fellowships and choir practices.

Between 27 March and 31 May, pastors in the RCZ had to find other means to reach their congregations, because in these nine weeks no services were held. A number of pastors, mostly from richer, urban areas, and all male, started livestreaming worship services on Facebook. Johanneke Kroesbergen-Kamps started researching these services soon after the start of the lockdown. During the weeks that followed, she found 32 congregations and pastors that had a presence on Facebook, out of a total of 203 RCZ congregations in the whole of Zambia. Most of these congregations are located in rural areas, especially in the poor Eastern Province. In these places, livestreaming a service is often financially and practically impossible because of a lack of funds for data and poor network coverage. What’s more, most of the members of poorer congregations have no means, financially or because they don’t have the necessary devices, to view services on the internet.

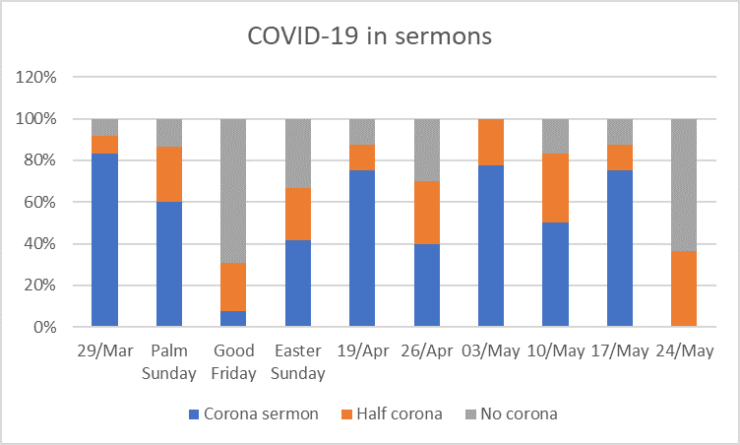

While the online services do not cover the breadth of the RCZ, they do give an insight into the way in which pastors try to give meaning to the COVID-19 pandemic when it first started spreading in Zambia. In the services, the Coronavirus is an important topic. Of the 109 collected services held in the time that the churches were closed, 78 (76%) explicitly mention COVID, coronavirus or pandemic.[1] Of all the services, 48% included what Johanneke calls a ‘Corona sermon’, in which the pandemic and its effects was the central theme. In another 23% of the services, the pandemic was not the main topic, but it was mentioned extensively in the prayers. Johanneke calls these ‘half corona’ services.

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic is an important issue in services held during the lockdown, but there are some interesting variations. Figure one shows that the share of corona services varied from Sunday to Sunday.

On the first Sunday in the period of lockdown, 29 March, over 80% of the services had a Corona sermon. On the last Sunday, 24 May, none had, although the pandemic was a topic in the prayers in a third of the services. Both Good Friday and Easter Sunday were also times in which the COVID-19 pandemic was not that important a theme in the service.

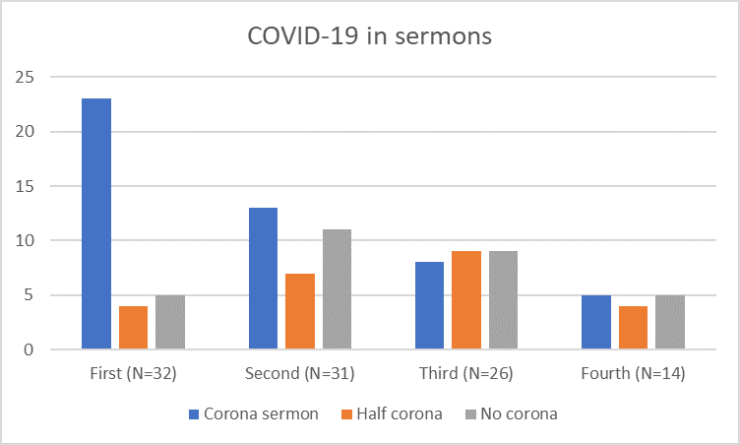

Another way of looking at the services is to follow not the Sundays, but the pastors who lead the services. Figure 2 shows that the pandemic is an important topic in the first online service of a majority of pastors, after which the importance decreases. Since not every pastor started to livestream services immediately, this tapering off cannot be seen when looking only at the particular Sundays.

Where possible, Johanneke collected at least three services of each pastor. Of these services, the first is most likely to contain a Corona sermon. On the last Sunday in lockdown, 24 May, no service had a Corona sermon, most likely because this was not the first online service for any of the pastors. Over time, the urge to make sense of the COVID-19 pandemic decreases. Life, including Sunday worship, is going back to a sort of (new) normal.

It has been widely observed that all over the world the language of war is an important register to speak about COVID-19.[2] The speeches of Zambia’s president, Edgar Chagwa Lungu, are a case in point. In his five speeches held during the period of lockdown, he uses the language of war 23 times. In all of these instances, it is the Coronavirus that needs to be fought and conquered by the government, by health workers, and by the preventative measures taken by all civilians.

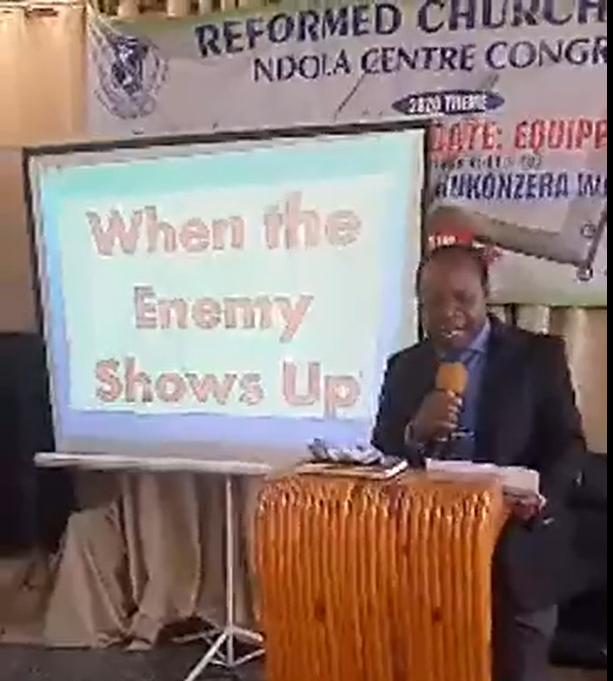

In the livestreamed RCZ services, the language of war is an important feature as well. Take, for example, a sermon entitled When the Enemy Comes, held on 29 March. It was streamed over 1,100 times, making it one of the most popular RCZ sermons in the whole lockdown. “Know that we have been confronted by a specific and special enemy, as the nation of Zambia, but also globally,” the pastor starts his sermon. “Everyone of us is able to mention who that enemy is: the Coronavirus.” The Coronavirus is an enemy of the people. The pastor continues by making an analogy with the biblical passage that describes how the Israelites flee Egypt. When they are on their way, they look behind them and see their enemy, the Egyptians, coming for them, and they get afraid. “There are two things that happen when the enemy shows up,” the pastor continues. “When the enemy shows up, there is a battle between two forces: fear and faith. In the passage that we have just read, we are seeing this battle. As we are battling against the Coronavirus now, I want to bring this to your minds, ladies and gentlemen, there is a battle. Within us there is the battle between fear and faith.”

In his sermon, the pastor states that fear is a bad response in a difficult situation. Fear magnifies the enemy, it instills a sense of inferiority, it erodes self-confidence, it breeds hopelessness and it makes you regret your choices. On the other hand, faith should be the response of a Christian in tough circumstances. Faith prevents panic, it focuses on God instead of the enemy, and it gives the power to see possibilities. He ends the service with the following prayer:

”We pray that this virus, heavenly God, will leave our nations, will leave this world in the mighty name of our Lord and Savior Jesus, the Son of the living God. We have tried many other ways, but, oh God, these other ways are proving to be very, very difficult. We are looking forward, heavenly Father, to singing songs of praise. This is our prayer and this is our faith, in the mighty name of our Lord and Savior Jesus, the Son of the living God. We are trusting in you because you are a warrior. Our God is a warrior”.

Like in President Lungu’s more secular speech, the Coronavirus is depicted as an enemy in this sermon. Unlike the president’s speech, it’s not just leaders, health workers and ordinary people who are fighting this enemy. It is God who is the main general in the battle against COVID-19.

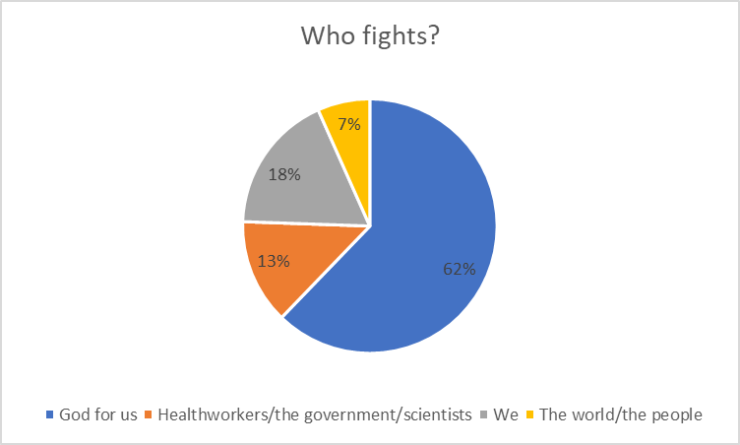

In all the services, the verb ‘to fight’ is used 75 times in about a third of the services. Figure 3 shows who it is that is fighting in the cases that the fight refers to the Coronavirus.

We, the people of the world and the people of the congregation, are fighting the Coronavirus, and so obviously do the health workers, the government and the scientists, but in a majority of the cases it is God who is fighting COVID-19 on behalf of humanity. This addition of God is an important difference between secular war language concerning COVID-19 and religious language. Another difference may be even more significant.

In the academic literature about the war language applied to the Coronavirus, it is taken as self-evident that fighting, battling, conquering COVID-19, and warriors who are in the trenches, are metaphors. In the sermon that was just summarized, the war language is a metaphor too. The pastor draws an analogy between the Israelites who were faced with an actual enemy, the Egyptians, and the people nowadays, who face a metaphorical enemy, the Coronavirus.

In the Christian language of faith, however, things are not always that straightforward. Another sermon, held on 26 April, also speaks about fighting the enemy of Coronavirus, but the connotations are very different. “We have a lot of enemies,” the pastor starts. “We have a lot of challenges that we cannot address on our own.” From the start, the concept of enemy includes not only actual enemies (like the Egyptians in the previous sermon), or specific metaphorical enemies (like the coronavirus), but all challenges that humans face. The message of the sermon is that we as humans cannot battle these enemies on our own; we need Jesus, the good shepherd who loves and cares for us. In this sermon, the concept of enemy is extended even further:

There are so many enemies that we cannot see. This time Coronavirus has come. Who protects you from Coronavirus? It is only Christ. Unless Christ watches over your life, you cannot survive the enemy of Coronavirus. We need Christ, we need the protection of Christ. We cannot protect ourselves from the threats of the world. We have got no power to protect ourselves from the enemy, from the devil, who comes to steal, kill and destroy.

Behind all the enemies we see in the world, there is one Enemy with a capital E, the devil. Throughout the sermon, the word enemy is used interchangeably for specifically the Coronavirus, for a broad range of problems and challenges, and for the devil.

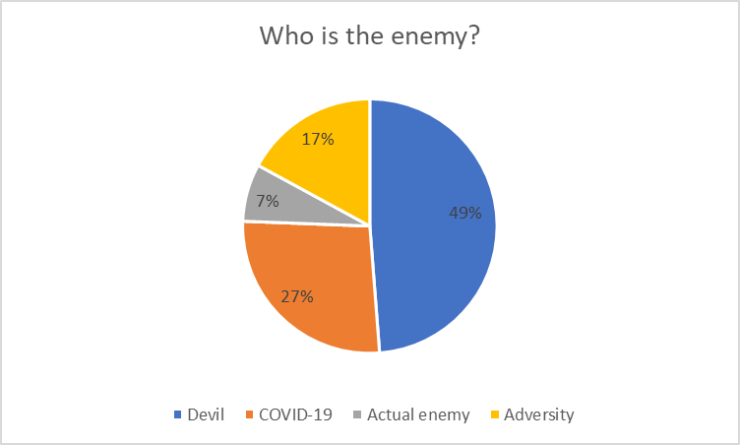

This use of the word enemy is not uncommon in the RCZ services. In the corpus of services held during lockdown, the word enemy is used 86 times in 24 documents. While not uncommon, it’s definitely not every pastor who speaks about any kind of enemy. But those who do use the word, use it to refer to different things, as figure 4 shows.

Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, the word enemy refers in a majority of cases, almost half, to the devil. After that come COVID-19, then adversities in general, and then actual enemies (like the Egyptians in the first sermon). Who or what a pastor means when he uses the word enemy is often not explicitly stated, but it is clear from the context, as it is in the second sermon discussed here.

The predominance of the connotation with the devil means that every enemy that is mentioned is quickly taken up into a theology that presumes an eternal fight between God and Satan. As Erik Meinema has argued earlier in this Dossier, the war language used to speak about the Coronavirus easily feeds in to a spiritual warfare discourse.[3] According to spiritual warfare discourse, human history is a battlefield between the powers of good and evil, of God and Satan. Secular war metaphors are readily interpreted in this framework by Christian audiences.

If fighting refers predominantly to God, and enemy refers predominantly to the devil, and both are likely to be interpreted from a spiritual warfare perspective, can we still say that the war language used to speak about the Coronavirus is a metaphor? It seems to be stretching the meaning of ‘metaphor’ to call it a metaphor, although what exactly counts as a ‘metaphor’ is the topic of an ongoing philosophical debate. It does not make much sense to say that for these pastors the war language is simply real, since, of course, they are aware that guns and bombs will not help here. On the other hand, they already take as given that there is a very real war going on between God and Satan, and the Coronavirus is seen as another ploy of this enemy. Yet, again what counts as ‘real’ remains the subject of even more debate than the label ‘metaphor’. Hermen Kroesbergen is a philosopher of religion who has written extensively on the religious language in an African context. He argues that, rather than discussing such labels, it makes more sense to clarify in what ways the role played by war language in connection with the Coronavirus may differ.[4]

When a politician like Lungu uses war language to speak of the Coronavirus, this is clearly only a way of speaking, and it could have been replaced by other ways of speaking without losing any meaning. Of course, a politician has his reasons to use particular phrases, but Lungu could have used different metaphors. He could have said that like a father he cares a lot about the victims of the Coronavirus and that he is engaged seriously in planting the seeds for finding ways to stop spreading the virus. Or he could have expressed himself without using any obvious metaphors. He could have used different words to say the same thing.[5]

This is not the case in spiritual warfare sermons about the Coronavirus. In these sermons, the war language cannot be replaced without changing the meaning. We could say that here the whole weight is in the picture, to use a phrase of the philosopher of language Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein was discussing religious language, in particular the expression ‘We will see each other after death’ said at someone’s probably last farewell. One could say ‘I am very fond of you’ instead, but, so Wittgenstein holds, this would not mean the same. Without this picture of life after death, some of the meaning is lost. By calling ‘We will see each other after death’ a picture, Wittgenstein does not diminish its value or truth, but summarizes the many way in which such an expression plays a different role in people’s lives.[6] Wittgenstein explains that he himself is not a religious person, but he can still grasp that the meaning of ‘We will see each other after death’ is not completely covered by the phrase ‘I am very fond of you’. Without this picture, what is being said would not mean the same thing.

The extent to which war language, used to speak about the Coronavirus, can be replaced by other ways of speaking without losing meaning, is important in understanding what is said about the virus. When a politician speaks of fighting the virus, most often this phrasing could be replaced easily without a change in meaning. The pastor who speaks of a battle between faith and fear speaks in a psychological or self-help way about war, and other pictures and metaphors from these realms could have been used instead. For the pastor who connects fighting the Coronavirus to spiritual warfare, however, the whole weight is in the picture. Replacing the war language would involve serious loss in meaning. So, what meaning is lost here that could not be covered by using other phrases?

People who speak of fighting in the context of spiritual warfare are aware that this fight is not an ordinary fight: they know that guns and bombs will not help here. Yet, they will, most often, emphasize that it is a real fight, maybe even ‘the real fight’, the one that gives meaning to all other ordinary battles. Of course, they know very well what counts as ‘war’ in general language, but within their way of looking at the world something else is the real war: the war between God and the devil.[7] In connecting a particular fight or occurrence to this deeper war, they change the perspective on this fight or occurrence. The fight or occurrence is placed in a new context and new connections are formed.

If the Coronavirus is placed in the spiritual warfare context, the perspective on the origins of the virus changes. It may still be the case that the virus did or did not transfer from animals to humans at a wet market in China, but whatever may be the physical origin, this was orchestrated by the devil. The devil is the real cause of this challenge for humanity, either because he has gained strength in the spiritual war, or because God allowed him to strike this blow, or because God used the devil to punish humanity or teach it a lesson. The real cause and the cause that matters changes when you place the Coronavirus in the context of spiritual warfare.

Similarly, the way to counter the virus changes. Scientists may still be needed to find a vaccine, but whether they will do so does not depend upon their own skills and resources anymore. It is now the result of God’s counterattack. Whether God can be moved to launch this strike, depends on the repentance of human beings, the forcefulness of their prayers, their moral behavior, and the like.

When war language is used in speaking about the Coronavirus in a context of spiritual warfare, then this language cannot be replaced without losing its meaning, because we cannot spell out all the ways in which this language changes the causes of and approach to the virus that are implied, and it makes no sense to try to do so either. In the war language used in these sermons, the whole weight is in the picture.

War language about the Coronavirus is often not much more than a metaphor, a ‘way of speaking’, but the whole weight can be in the picture as well, as is the case, for example, in the sermons that connect the Coronavirus to a spiritual warfare theology.

Johanneke Kroesbergen-Kamps & Hermen Kroesbergen

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.

In April 2020, Johanneke Kroesbergen-Kamps already published a blog article related to Corona in Zambia. Click here to read ”Mediating the presence of God online”.

References

[1] The total number of services was much greater and impossible to keep up with. In the end, Johanneke chose to transcribe only services held on Sundays (most congregations also have a Wednesday prayer service) and on religious festivals. For each pastor she aimed at transcribing at least three services.

[2] See for example Saiba Varma (2020). “A Pandemic Is Not a War: COVID-19 Urgent Anthropological Reflections.” Social Anthropology, doi: 10.1111/1469-8676.12879, but also Mauro Bonazzi’s piece ”War on words” in Religious Matter’s Dossier Corona (weblink) and Anders Engberg-Pederson’s blog on b2o (weblink).

[3] See Erik Meinema’s piece in Religious Matters’ Dossier Corona, entitled ”’Quarantine is Godly’, but in the fight against Corona, ‘the devil is in the details’ (weblink).

[4] This is the approach Hermen argued for and applied in: Hermen Kroesbergen 2019, The Language of Faith in Southern Africa; Spirit World, Power, Community, Holism, Cape Town: AOSIS Scholarly Books (link to the publication).

[5] Although an interesting analysis by Yuval Benziman (2020) of the war language used by leaders argues that it is precisely using the frame of a war that made it possible for leaders to demand action of the people and reduce their freedoms. See Yuval Benziman (2020). “‘Winning’ the ‘Battle’ and ‘Beating’ the COVID-19 ‘Enemy’: Leaders’ Use of War Frames to Define the Pandemic.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 26(3), 247-256.

[6] In The Language of Faith in Southern Africa, Hermen illustrates this by listing the differences between praying to St. Anthony when looking for a parking space and using a parking app (Kroesbergen, The Language of Faith, 97-104).

[7] In Hermen Kroesbergen 2020, ‘God regulates the church, even if he doesn’t; Wittgensteinian philosophy of religion and realism’ in Philosophical Investigations 43.3, 254-283, Hermen shows that such re-definitions presuppose an awareness of the ordinary definitions, illustrating this by discussing the suggestion from the Gospels that of the praying Pharisee and Publican, only the latter is really praying.