Mauro Bonazzi

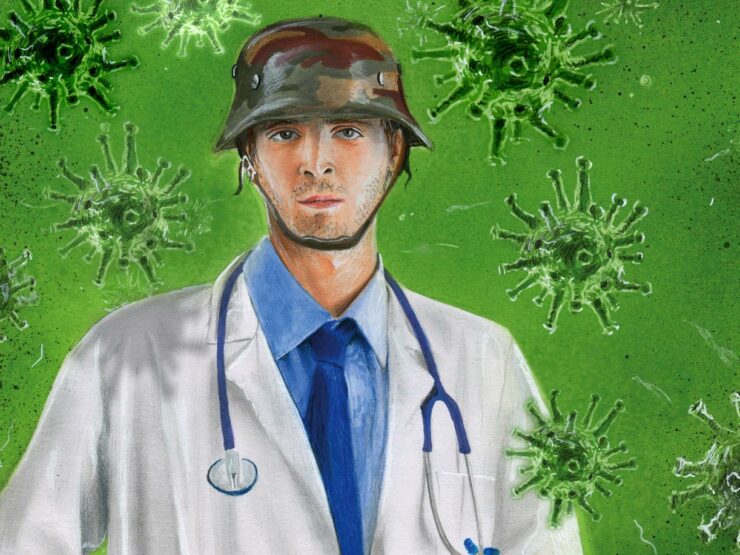

There is no time to debate in war, one must act. Closing ranks, setting aside the differences and fighting together. As for the rest, there will be time later. During these demanding months, we have been repeatedly told that we are at war. In Europe, everywhere, all political leaders have made use of this language to justify their decisions and measures. Then, the war is over, and people start rebuilding. And today?

Is the war over, or does it go on? What should we do then, go out, stay home, what? Interestingly, only a world leader has never made use of war metaphors: Angela Merkel. Perhaps because in Germany these metaphors refer to a past that still resonates; perhaps because of her composed and reserved personality, reluctant to impress. The fact is that Angela Merkel never evoked war scenarios: she has tried to avoid too many metaphors, and when she used them, she has spoken of ‘thin ice’ or ‘long distance running’. She has provided a temporal perspective when others were entrenching themselves in the here and now. She has turned to people’s intelligence, not to their emotions.

Is it a coincidence that Germany is doing better than many other countries? It certainly shows that even words matter, especially in politics. Because it is the words that help us give an order to the reality around us: and words, according to the sophist Gorgia, are like a drug, they can treat or poison, it depends on how we use them. Many, on the footsteps of Giorgio Agamben, suspect that the use of war metaphors, a permanent evocation of emergency, aims at limiting democratic freedoms. In part perhaps, as the case of Hungary shows. But in most cases, it is more likely that this language has been exploited to hide indecisions and uncertainties and, unfortunately, in some cases, also unpreparedness. In short, in this second case too, there has not been a good service to democracy, which is a system of responsible citizens, not children to be frightened or consoled according to the circumstances.

This is the translation of Bonazzi’s piece [May 25th, 2020] in the Italian newspaper Corriere [click here].

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.

Bionote

Mauro Bonazzi (PhD Milan, 2003) holds the Chair of History of Ancient and Medieval Philosophy at the University of Utrecht. Before he was professor at the University of Milan and taught as invited professor in the universities of Bordeaux, Lille, Clermont-Ferrand and the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris.

His main areas of research are Plato and Platonism, and Greek Political Thought. He is also interested in the use and abuses of Ancient Greek thought in modern philosophy, from Nietzsche to the Nazi ideologues, from H. Arendt to L. Strauss. He is currently working on a book on the Sophists, to be published by Cambridge UP. His main publications include: Processo a Socrate (Laterza, Rome 2018); À la recherche des Idées: platonisme et philosophie hellénistique d’Antiochus à Plotin (Vrin, Paris 2015). He writes a weekly column (‘Lezioni di filosofia’) for ‘Sette – Corriere della Sera’.