Jing-Yi Magraw

In July 2020, I decided to buy a hamster. Although it was in the midst of the first outbreak of the pandemic, the decision was not part of the frenzy of pet buying that the pandemic instigated. I had been wanting to buy a hamster for a long time, and, by July, I had already spent almost a year joining, and scrolling through, Facebook groups dedicated to hamsters and hamster owners. Some of these groups have well over 50 000 members from around the world, and dozens of new posts are made every day in these groups – ranging from people asking advice about hamster food and cage requirements to owners posting photographs of their hamsters just to share with the group. One of the more frequently discussed, and posted about, topics in these groups is the loss of a beloved hamster. These posts are often the most reacted to, and commented upon, with people coming together to share their own experiences of coping with the loss of a pet. The emotions surrounding these small pets are often hard to quantify, and some owners will even make posts on the anniversary of a past pet’s death, noting that they still mourn for them and miss them even years later. What these Facebook groups reveal is that the relationship between these human owners and their domesticated hamsters runs far deeper than many might suspect.

The hamster is a domesticated animal, kept in many childhood homes, and yet for all intents and purposes it does not seem to offer any concrete benefits to its human owners. It does not appear to return affection in the same way that a dog may do by seeking out, and enjoying, its owner’s company (although this is something that is often contested amongst hamster owners). Hamsters also do not produce wool, milk, or meat in any quantity that is of assistance to a human’s daily life, unlike other domesticated animals such as cows, goats, and sheep. Indeed, to use a hamster as an example for the significance of the relationship between humans and domesticated animals could appear to be counterproductive on some levels. However, the apparent lack of reciprocal benefits that a hamster provides, in the eyes of many, are precisely what makes the hamster an interesting example of this human-domesticated animal relationship.

The process of the domestication of animals itself is an integral part of Ian Hodder’s argument in his article “The Entanglement of Humans and Things: A Long-Term View.” In the article, Hodder discusses the entrapment of human beings, and examines human dependencies on ‘things’, using domesticated animals as one example of this ongoing entrapment and dependency. Through domesticating herd animals, humans were rewarded with products such as milk and meat. However, in this process of domestication, human beings themselves became trapped “into the care of domestic flocks.”[1] This dependency evolved in both directions: not only did human beings become dependent on domestic animals for sources of food, clothing, and other products (consider the use of animal waste products to build shelter in certain cultures), but this dependency was reciprocated as animals gradually began to rely on humans for food, healthcare, and shelter. Indeed, although it is certainly true that some domesticated animals could still thrive in the wild today, many would not survive long if they were to be released from the care of humans, so deep does the dependency now run.

Thousands of years after animal domestication first began, the 21st century has seen a curious rise in a tendency for humans to promote domesticated animals to another level of dependency beyond the practical reliance on animals as assisting in work or transport, or as producers of meat, milk, and wool. This new level, ‘pets’, is most visible when considering the different criteria that a ‘pet’ meets, as opposed to a more ‘regular’ domesticated animal. Pets are, for instance, “allowed in our homes, they are given names, and they are never eaten.”[2] Indeed, beyond this, pets are “not valued for their utility, but for the emotional support they provide.”[3] This emotional support can be derived from a wide variety of animals, ranging from the more popular choices of dogs and cats, to the perhaps more controversial options such as snakes or tarantulas. This provides a nuance to the ‘entrapment’ that Hodder discusses, as human beings not only become entrapped in their relationships with domesticated animals for utility, but they may also become entrapped in their dependence on animals for emotional well-being.

This entrapment, which, as Hodder notes, is ever-increasing as humans bring more and more ‘things’ into the sphere of reciprocated dependency, is precisely why the human-animal dependency is interesting to consider from the lens of religious studies. Entrapment implies not only that humans rely on domesticated animals for practical purposes, but that these animals are also brought more deeply and irrevocably into the fold of religion. Consider the Christian belief in Heaven, as one more prevalent example of this. In contemporary society, especially Euro-American society, human beings are not the only ones that are referred to as ‘crossing over’ or ‘ascending’ into Heaven when they pass away. Indeed, popular culture often readily embraces domestic animals as being able to reach Heaven, often as a way of comforting owners or children.

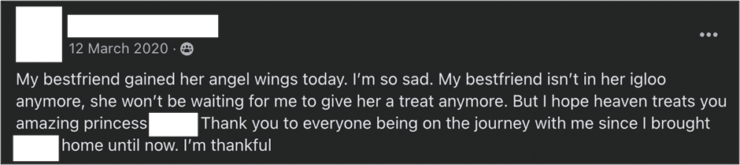

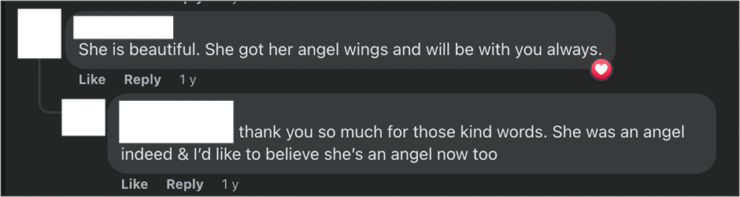

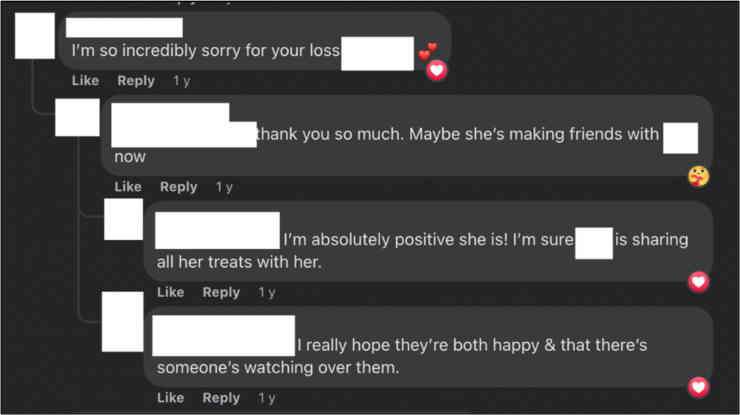

My hamster passed away in April 2022, and, although I never posted anything on Facebook about this myself, the entire step-by-step process of how to deal with your pet’s passing was detailed in numerous past posts from other bereaved owners, and they were helpful to me for both practical and emotional reasons. Many of these posts and threads, often by distraught owners asking the group for advice on how to cope, contained comments by other group members that either alluded, or explicitly stated, that the recently passed hamster would now be in Heaven. These hamsters are also frequently referred to in the group as having ‘gained wings’ or as being ‘angels’ (or, often, as having ‘angel wings’ – see Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

There are also often mentions of the hamsters being ‘in a better place’ now and, in the case of an owner who might have had multiple hamsters pass away previously, that they have joined their ‘siblings’ in this better place (see Fig. 4).

This example of entrapment above highlights the manner in which dependency goes beyond a practical, physical nature. Religion, in this case, sheds light on the level of entrapment (both physical and emotional) that occurs between domesticated animals and human beings: in ‘allowing’ for these animals to also join the human afterlife, humans are demonstrating the depth of dependency. Indeed, research has indicated that, for many, pets are even considered to be part of the family, with people stating that pets “give as much as they receive, even if the support they provide cannot be neatly plugged into standard social network categories.”[4] These domesticated creatures are so vital to the human perception of the world, the entrapment so deep, that even the afterlife cannot be envisioned to be ‘only human’ but, instead, must be made available to beloved pets so as to continue allowing human beings to live their lives beyond the grave in the same manner as they do when they are alive.

As Hodder notes, “we are only human through things.”[5] Understanding the human-animal dependency through the lens of religion offers us a glimpse into how embedded these ‘things’ (in this case, animals) are in our existence. Religion shows us that it is not enough that these things are what make us human in this lifetime: we must also allow these things to enter into the next life, the afterlife, with us. To say goodbye forever to our pets, to bar them from entrance into Heaven, would mean being able to envision being a human in the afterlife without them. Yet Hodder’s theory of entrapment raises the question of whether it is even possible to be human without our ‘things’.

Jing-Yi Magraw is currently a Religious Studies Research Master’s student at Utrecht University. She completed her undergraduate degree at University College Roosevelt, where she majored in Religion, Linguistics, and Literature, and minored in Law – all four disciplines continue to influence her research projects. Her main research areas are the intersection between religion and law, specifically focusing on interpretations and applications of law to minority and/or indigenous religious groups, and she often explores the different definitions of ‘religion’ both in legislation and in wider society in order to come to a more nuanced understanding of the (mis)communication between a country’s citizens and its law.

References

[1] Ian Hodder. “The Entanglements of Humans and Things: A Long-Term View”, New Literary History 45, no. 1 (2014): 30.

[2] David D. Blouin. “Understanding Relations between People and their Pets”, Sociology Compass 6, no. 11 (2012): 858.

[3] Blouin, 858.

[4] Susan Phillips Cohen, “Can Pets Function as Family Members?”, Western Journal of Nursing Research 24, no. 6 (2002): 632-633.

[5] Hodder, “The Entanglements of Humans and Things”, 34.

Bibliography

Blouin, David D. “Understanding Relations between People and their Pets.” Sociology Compass 6, no. 11 (2012): 856-869.

Cohen, Susan Phillips. “Can Pets Function as Family Members?” Western Journal of Nursing Research 24, no. 6 (2002): 621-638.

Hodder, Ian. “The Entanglements of Humans and Things: A Long-Term View.” New Literary History 45, no. 1 (2014): 19-36.