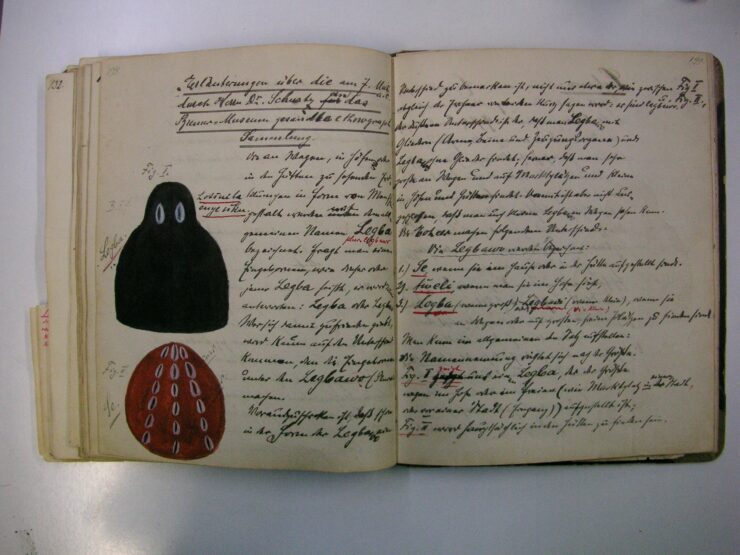

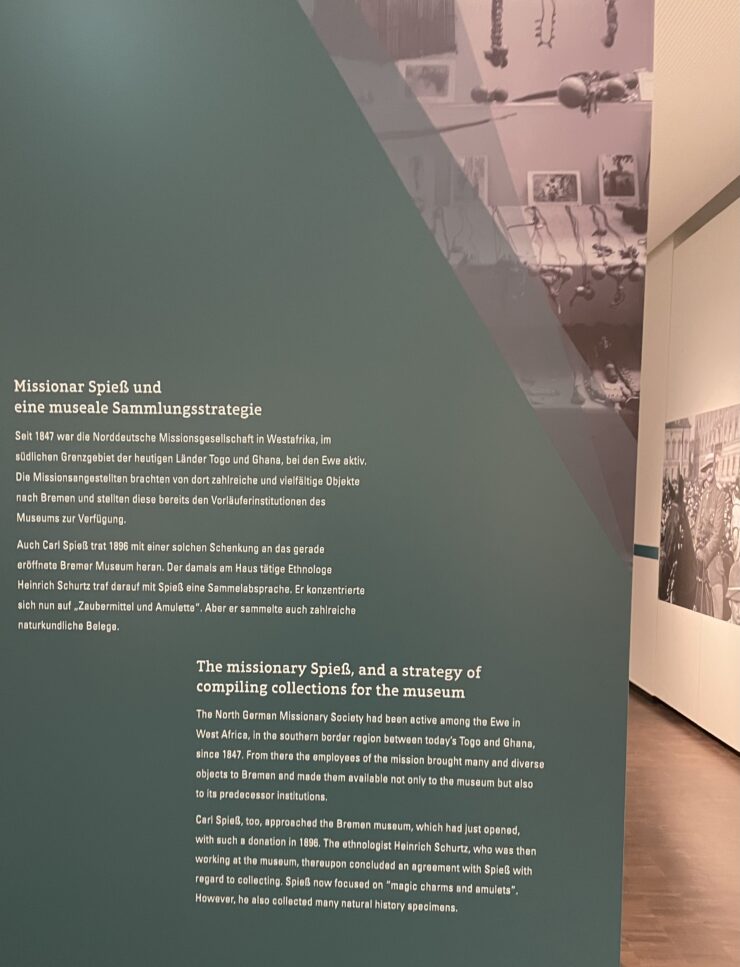

The Übersee-Museum Bremen hosts a collection of items that were assembled by the missionary Carl Spiess (1867-1936), Norddeutsche Missionsgesellschaft (NMG), on behalf of Dr Heinrich Schurtz (1863-1903), anthropologist at the Städtisches Museum für Natur-, Völker- und Handelskunde (today the Übersee-Museum). Schurtz asked Spiess, who worked as a missionary in the area inhabited by Ewe-speaking people (today’s South-eastern Ghana and Southern Togo) that was placed under German colonial rule (1884-1914), to “turn his attention to amulets and magic objects, since he would certainly be the first to succeed in acquiring such objects and in discovering their purpose with the help of new converts.”[1] During his many trips through the mission area, alongside preaching to what the mission regarded as “heathens” who were to be called to convert and turn to the Christian God, Spiess collected many items. A great deal of these are small legba figures and dzokawo (means to do magic, such as charms and amulets). Spiess wrote several diaries (kept in the Staatsarchiv Bremen) in which he reported about his travels, and the collections sent to Bremen.

The provenance of the items is only rarely documented, but it is certain that the mission required new converts to give up and hand in items related to personal protection. These were reframed as instances of “idolatry” by the missionaries, who strove to make Ewe people convert to Christianity. The collection of items spoke to Schurtz’ longstanding interest in magic (Zauberei) as the origin of religion. The items were sent to Bremen by Spiess for purposes of research and display. Part of the Spiess collection, and items from other collectors in the same area, was shown in the museum until the WWII, when the museum closed down and its artefacts were sent to a safe place. Afterwards, the items from the Spiess collection were only shown occasionally. Recently, in the context of rethinking its history and the provenance of the ethnographic collection, the museum opened a vitrine devoted to the collection Spiess, pointing at the link between the NMG and the museum and the question of how it was collected. For long, the existence of the collection was barely known to a German and African public.

In 2019, Birgit Meyer and Silke Seybold (curator Africa, Übersee-Museum) took the initiative of developing a collaborative research project with scholars from Germany, Ghana and Togo. In January 2020 Meyer visited Ghana and spoke to traditional priest Christopher Voncujovi (AfrikanMagickTemple Accra) about the collection on the basis of pictures. Due to the “Corona”-pandemic, the ideas for a collaborative research visit could only be discussed online. So far, the research team includes Sela Adjei (National Film and Television Institute, Accra), Kokou Azamede (German Studies, Université de Lomé) Kodzo Gavua (Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, University of Ghana), Angelantonio Grossi (UU), Malika Kraamer (MARKK, Hamburg), Birgit Meyer (UU), Silke Seybold (ÜM), Ohiniko Mawussé Toffa (Ethnological Museums Leipzig and Dresden), and Christopher and Kofi Voncujovi (AfrikanMagickTemple Accra).

From 11 to 16 September 2022, our team could finally meet on location in the Übersee-Museum in Bremen, hosted by Silke Seybold, and assisted by Petra Schierholz and Tjark Froehner. All discussions were audio-recorded (now awaiting transcription), and partly filmed by Grossi. Prior to beginning our investigations and deliberations, Christopher Voncujovi prayed to and informed the spirits imbued in the items about our project. On the first day we discussed the background of the collection: how its existence is a consequence of the NMG’s paternalistic and racist stance towards Ewe people as “heathens” to be converted to Christianity (Toffa), the discourse of “idolatry” and “fetishism” that formed the lens through which Ewe spirituality was misrepresented (Meyer) and the history of the collection with regard to Spiess’s activities and the ways in which the items were preserved and displayed in the museum (Seybold).

On the second day, Silke Seybold took us to the vitrine about the Spiess collection which is part of the museum’s reflection about its past and the provenance of its artefacts. She explained the instances in which Spiess provided information of the provenance of particular items. An animated discussion ensued about Spiess’ deep interest in and knowledge about Ewe spirituality. Did he know more and engage more deeply than he himself was prepared to release in his writings? In any case, the collection of items assembled by him offers a viable entry point into the late 19th-century Ewe world in the wake of colonization, as well as into the missionary misrepresentations and assaults of indigenous material forms and meanings as part and parcel of the German colonial project, and the role of ethnological museums therein.

Afterwards we encountered the huge collection of dzokawo, assembled by Silke Seybold, in the public depot. Prayers were offered and during the examination of selected dzokawo, afa diviner Kofi Voncujovi mobilized the afa oracle. We focused on several distinct dzwokawo from the angles of scholars and practitioners, learning a lot about the materiality and meaning of distinct items, and getting a glimpse of their use and importance for indigenous Ewe society prior to colonization and evangelization.

The third day took us to the Museum am Rothenbaum, Kulturen und Künste der Welt (MARKK) in Hamburg, where Malika Kraamer introduced us to a collection of items from the Ewe area that reached the museum through the NMG mission inspector Martin Schlunk. Only few items of this collection survived a bomb attack in WWII, but they are represented through hand-made drawings. We also looked at and discussed a collection of postcards and photographs taken by NMG-missionaries. Spiess and Schlunk both met during a trip to West Africa and later worked together in Bremen, which shows the importance of the topic of networking and influence.

Back in Bremen, the fourth day was devoted to the legbawo. Here we did not only look at legbawo taken to Bremen by Spiess, but also by trading company Vieter and Freese. We proceeded in the same manner as we did when investigating the dzokawo, invoking the calling on the afa oracle. Again, Christopher Voncujovi could tell us a lot about the collection, also pointing out that some items had falsely been categorized as legba-figures.

We started the last and fifth day with a presentation by Kokou Azamede, who told us about his research in congregations of the Evangelical Presbyterian Church (that came out of the NMG mission) where he asked contemporary church members about their attitudes towards items discarded by the mission as “idols” and “fetishes” and their ideas about restitution. This lecture served to highlight the complexities of the current situation, in which Christianity has become a major public force in Southern Ghana, while at the same time the role of so-called traditional religion – or more aptly: indigenous spiritism- is still contested, yet also increasingly appreciated. Clearly, a focus on items such as those in the Spiess collection can prompt discussions about the implications of colonialism and missionization for contemporary society, and open up new alleys for postcolonial criticisms, appreciation of indigenous cultural heritage, and calls for restitution and repatriation. Together with our guests Hans Peter Hahn and Niklas Wolf, we spent the remainder of the day to discuss our findings, prepare our presentations at the Unpacking missionary collections workshop in Utrecht and make plans for the future.

Our team aims to pursue the research on the Spiess collection, by tracking the trajectory of the items taken from local Ewe people to Bremen, and the subsequent reframing due to missionary, anthropological and museal categorizations. This will require deep investigations into the collection itself, the activities of the NMG among the Ewe, the texts written by missionaries and scholars, as well as into current apprehensions of such collections as a resource for knowledge about colonial entanglements and possibilities of repair. There is much to be done, and we believe that this can only be accomplished through collaborative research.

[1] Heinrich Schurtz, Zaubermittel der Evheer, Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie 14, 1901: 1, translation Andrea Scrima.