Roos Dorsman

On Thursday September 23 of this year, I defended my PhD thesis entitled The New Orleans Voodooscape: Ethnography of Contemporary Voodoo Traditions of New Orleans, Louisiana. In this study I explored the role of contemporary voodoo practices in New Orleans society. I worked on my PhD research as part of the interdisciplinary project Currents of Faith, Places of History: Religious Diasporas, Connections, Moral Circumscriptions and World-Making in the Atlantic Space.[1]

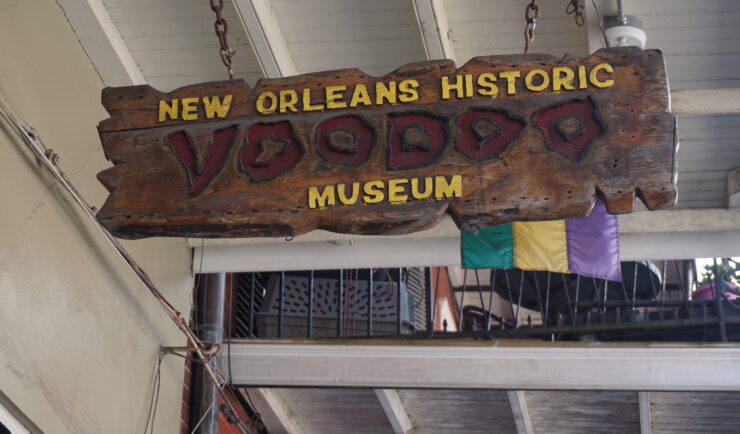

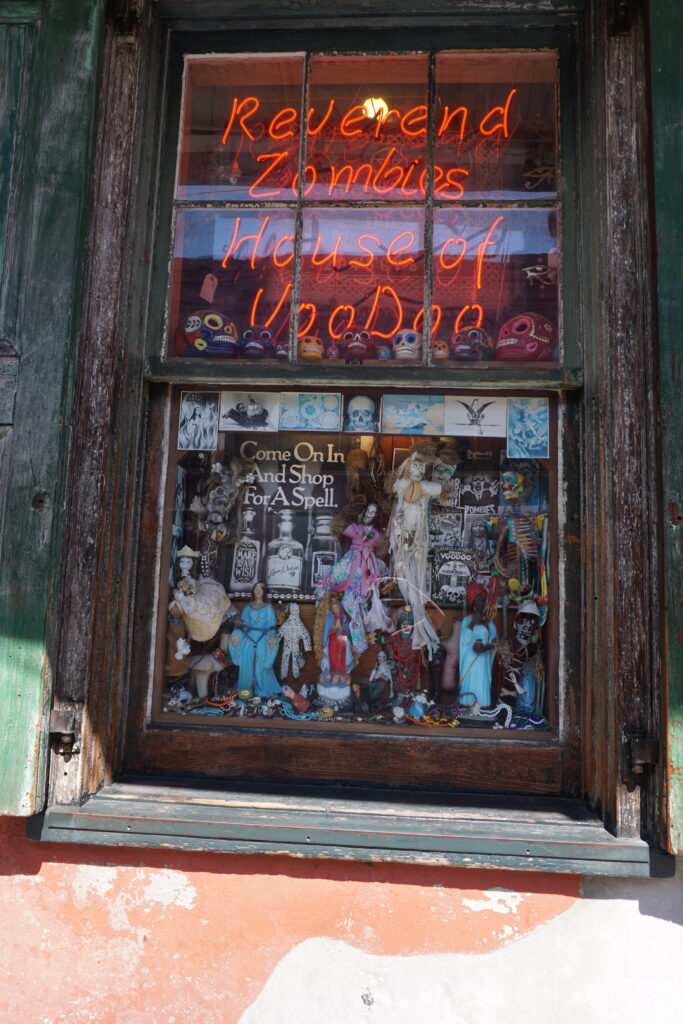

In New Orleans, Louisiana, references to voodoo can be found everywhere. There are many tourist tours that include the word voodoo, like the Voodoo Bone Lady and the Voodoo and Cemetery Tour. When I started my fieldwork, I wasn’t necessarily looking for ‘Jaw Dropping, Heart Stopping, Immensely Thrilling & Spine Chilling Fun’ (website voodoo bone lady). But even though at first sight this might not seem ‘real voodoo’, or ‘the real deal’ as practitioners call it, actor often take part both in the commercial and in the more spiritual domains of voodoo.

The more time I spent in New Orleans, the more I realized that there was no such thing as an opposition between the ‘tourist trap’ and the ‘real deal’, but rather a landscape of domains of voodoo that partly overlap and are even entangled. To do justice to the full complexity of voodoo in New Orleans, I coined the term voodooscape. This concept allows me to include not only religious practices that form an important part of voodoo, but to also encompass the different, ever widening circles connected to voodoo including actors ranging from: initiated priests, priestesses, and initiates, to their clients and voodoo entrepreneurs, to tourists. The voodooscape, then, does not only include all these human actors, but also sites such as shrines, shops, parades, and music. In navigating the voodooscape, people negotiate – and transgress – the boundaries between the voodoo houses on the one hand, and other more public domains, on the other. In these negotiations, visibility and secrecy play an important role, as does the discussion about representation in the public domain and media. Practitioners are aware of all the dimensions and domains and discuss these with each other, as they did with me: an inquiring, curious anthropologist. Questions about which aspects of the voodoo houses can be brought into processions, or what knowledge can be made public, what should remain a secret, and what kind of voodoo is the ‘real thing’, are constantly debated, criticized, contested, and negotiated. And it was precisely these negotiations that I was interested in.

An example of a place where many of the domains of voodoo come together are the several botanicas, or supply stores for rituals. This might speak to the readers of the Religious Matters blogs particularly, because it relates to the materiality of voodoo rituals:

It was a sunny day in January 2015 when Ryan and I entered F&F Botanica, the supply shop for rituals in various traditions, or in Ryan’s words: ‘the Walmart of voodoo and Santería’[2]. The first impression was overwhelming as the walls of the large shop were filled with shelves that contained statues of saints and spirits, herbs for cleansing baths, candles for rituals and sprays for everything one could wish for, such as ‘come to me love’ and ‘go away evil’ spray. To the left side of the store was a counter parallel to the full length of the wall, where three shop assistants were advising and helping customers continuously. Ryan had taken me to the shop to show me how active the inhabitants of New Orleans practice both voodoo and Lukumí (also known as Santería)[3] and how these two worlds were entangled in this specific store. After we explored the store for a while, a shop assistant walked up to us. He greeted Ryan, who he had known for years, warmly and was excited to hear about my research. With great enthusiasm he showed us a statue of Saint Barbara, whose imagery is often used as representative for the spirit of Shango or Xango. What was special about this specific statue is that the figure was black skinned. It is a positive development, the shop assistant assured us. According to him, for too long white saints had represented black spirits. And as there is no official oppression any longer, practitioners should liberate themselves and take new imagery for their spirits, according to him.

This first visit to the largest local supply store illustrated several elements of the voodooscape that I explore in this work. In this store, one can find internal diversity, community building, healing, activism, a reference to the history of oppression of voodoo religion, and commercialism. As I will illustrate throughout various chapters, commercialism has always been an essential part of the voodooscape. And whereas the degree to which it does so might have changed, I maintain it is part of the continuity in the voodooscape. The comment about the skin color of the statue is a reference to the history of violence in the city and the activism that has always been present. All customers visiting the store are looking for some kind of healing for the different aspects in life. The shop itself, its owners and the customers are facilitating community building over a broad range of practitioners, thereby representing the internal diversity of the community.

(Fragment from the introduction of my thesis (page 10))

The aim of my dissertation is to demonstrate why the concept voodooscape is essential to tell and analyze the story of voodoo in New Orleans. To do so, I looked at all aspects of voodoo in the city and historized the voodooscape in relation to certain key historic events, namely: slavery, Hurricane Katrina, and the Black Lives Matter Movement. My contribution lies in the fact that I advocate not only the inclusion of the more obvious religious aspects, but also the political use of rituals by activists, commercial references to voodoo in the tourist industry, and the voodoo practices and ideas that are manifested in daily life. In my view, voodoo should not be reduced to a cult or a religion, but not be restricted to pure commercialism or tourism either. It includes the full spectrum with all the dimensions that I have previously named. Therefore, I argue that the social arena of contemporary voodoo in New Orleans is a ‘scape’ or an environment through which several socially relevant dimensions are displayed and connected, namely: race, politics, music, art, heritage, tourism, and commerce. Through these dimensions and because of the processes of authentication and internalization of voodoo heritage by the actors in the field, voodoo is still relevant in New Orleans today. The concept of voodooscape is a useful notion to highlight the complexity of the transatlantic network and it serves to introduce globalization into voodoo studies by incorporating the fact that New Orleans voodoo has influences from many regions. The concept facilitates a more nuanced understanding of voodoo in which room is made for an analysis of the complexity of influences; the wide range of activities, not only ceremonies, but also rituals in daily life; the range of economic activities that accompany the voodooscape; and the role of music.

at the City Park.

One aspect to voodoo that I found particularly interesting is its relationship with activism.

Like music, activism is an essential part of all domains of the voodooscape. The collective trauma of the violent history of slavery is part of the current collective identity of African Americans in New Orleans. The collective memory of the disrupted African history gives shape to individual memory and the other way around. I found that the collective memories of the history of slavery and the lived experiences and individual memories of the disaster that ensued from hurricane Katrina (and the political mismanagement in the aftermath) still impact feelings and behavior. These memories are triggered by current events such as police violence. Healing rituals are often part of activist rallies, and these rituals include references to voodoo. The re-embodied knowledge that is part of black activism is essential for the voodooscape. The practice of voodoo itself should also be interpreted as an act of resistance to the social order. Based on the ethnographic examples that I present in my thesis, I argue that the voodooscape mobilizes memories of slavery. At the same time, the voodooscape mobilizes activism to strive for healing, both individually and collectively.

Coming back to the botanica and the commercial aspects to voodoo that I started this blog with, I observed that nowadays, there is an extreme level of commodification of voodoo in New Orleans. Though the current level is extreme, commercialism is not a contradiction with ‘real’ voodoo, as it is perceived by its practitioners. In fact, there has always been a certain level of commercialism. Since the 1800s people paid with money or offerings for services by healers. Thus, the debate within the voodooscape is not so much about the idea of whether commercialism is part of ‘real voodoo’, as it is about who should benefit from it. Many practitioners maneuver between the different levels of the voodooscape. They manage to do what is real to them and combine it with making a living on other levels of the voodooscape. To them, this does not imply a contradiction, but rather a way of life that helps them to continue voodoo traditions.

For a more elaborate analysis of the voodooscape, including many photos and ethnographic examples of the debates surrounding ‘authenticity’, I kindly invite you to read the full text of my PhD thesis, that is open access and available online via the following link:

The New Orleans Voodooscape – Roos Dorsman

Bio

Roos Dorsman is a cultural anthropologist from the Netherlands. After obtaining her BA in Cultural Anthropology and Development Studies at the Radboud University in Nijmegen (Netherlands), she deepened her training as an anthropologist by following additional courses on migration, violence and representation in art, at the University of Utrecht (NL) and Universidad de Granada (Spain). Her BA thesis ‘Stilte of erkenning [silence or acknowledgement]’ was a literature study on the relationship between the Netherlands and Suriname concerning the history of slavery. During the MA program on Anthropology of Mobility at the Radboud University she wrote her thesis ‘Thuiskomen in Switi Stranan [coming home in Sweet Suriname]’, in which she investigated the phenomenon of roots tourism from Dutch Surinamese people to Suriname from the angle of the concepts of home and belonging, diaspora and identity.

In September 2021, she successfully defended her PhD on contemporary voodoo traditions in New Orleans, Louisiana (USA) at the Université libre de Bruxelles (Belgium), engaging with the debates surrounding the concepts of authenticity, (traumatic) memory, heritage, and commodification. Her research topics of interest include memory, migration, transnationalism, commodification of culture, gender, cultural heritage, construction of identity, violence, Suriname, the Caribbean, and New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

References

[1] The project was led by prof. Ruy Blanes and funded by Humanities in the European Research Area (HERA). The thesis was supervised by prof. David Berliner (Université libre de Bruxelles) and co-supervised by prof. Birgit Meyer (Utrecht University). I received additional funding from Fondation David et Alice van Buuren.

[2] Religion from Cuba, also known as Lukumí, Lucumí and Regla de Ocha.

[3] Both voodoo and Lukumí are syncretic religions that are built around worshipping spirits and ancestors. The most visible syncretic aspect of these religions is the use of imagery of Catholic Saints to represent certain spirits.