Ernst van den Hemel

In contemporary globalized media-culture, most of us have received the Christmas narrative in some way shape or form. Whether it is through Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, countless Hollywood movies, children’s cartoons or songs, Christmas is not just the time to be merry, it is also a time in which people are reminded of the importance to be concerned about Christmas, to convert people to the true spirit of Christmas or to enjoy stories in which enemies of Christmas get their deserved comeuppance.

In this blogpost I suggest there is a connection between the popularized narrative of Christmas as we see it in Christmas movies and contemporary polarization as it unfolds during this holiday season.[1] ‘Christmas’, I argue, is a script[2] involving all the senses. The script is used to express (and increase) a sense of belonging but also of fear and concern. This allows us to better understand how, in times of Covid-19, Christmas is connected to deepening polarization between ‘the people’ and its enemies.

But first, let me sketch the script of Christmas as it is expressed by virtually all mainstream Christmas movies. Whether it is, to give a random sample, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843, first movie rendition 1901 followed by countless others), Miracle on 34th Street (1947), How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1967), Scrooged (1988), Home Alone (1990), or more recently, The Happiest Season (2020), the recurring narrative structure of Christmas movies presents Christmas as under attack and at risk of being forgotten, canceled, suppressed. Luckily, whether it is through divine intervention, comedic irony, the converting power of the naive wisdom of children or through justified comedic violence, the enemies of Christmas are served a reckoning and the (Christmas)day is saved.

Christmas movies apply this script to address different circumstances and contexts. They offer a moralizing (frequently comedic) mirror of the times in which they were made. For instance, Dickens’ hugely influential A Christmas Carol (and the many movie adaptations) address poverty, selfishness and the loss of moral values in times of individualist capitalism. Miracle on 34th Street (1947) addresses the importance of belief and family in the face of hardship and social disintegration, The Grinch Stole Christmas (1967) reminds the viewer about the importance of convincing (or converting) extravagant loners of the inclusive Christmas spirit, Scrooged (1988) starring Bill Murray drives home a critical message about soulless business executives, and even the cartoonishly violent perennial Christmas classic Home Alone (1990, see figure 2) addresses concern that working parents might (literally) forget their children, who are then left to deal with criminals and lawlessness on their own. The moralizing beginning and final scene of Home Alone reflects a late eighties early nineties concern of the impact of working parents on the nuclear family and can be seen as a comedic expression of the 1980’s backlash against feminism. In 2020, The Happiest Season presents a story of the effects of intolerance towards homosexuality, inscribing diversity as a Christmas message.

Christmas movies, in short, are a good indicator not just of what is valued and shared but also of what is seen as a threat to values and inclusive togetherness. In this manner, by evoking emotions as pity and compassion with the victims and ridicule and aversion for the enemies of Christmas, a pedagogical script is circulated and applied each year. Through this script an appreciation of Christmas is instilled in viewers, but also a concern for and combative attention to that which is seen as a threat to Christmas and the community.

In this script, an important role is reserved for the senses. The smell and taste of food, the sounds of the words ‘Merry Christmas’ and the jingling of bells, the visual spectacle of tree and decorations, the tactile interactions with bodies (embraces, hugs and kisses) or the exciting coldness of snow, all senses are addressed in the pedagogy of Christmas. Enemies of Christmas are presented as withholding these sensory experiences from the people (the Grinch, for instance, in his attempt to steal Christmas, steals all ‘the ribbons, the wrappings, the trimmings, the trappings’). When, at the end of the script, the enemies of Christmas are defeated or converted, a cornucopia of sensory experiences is let loose, frequently culminating in a spectacular lighting of decorations, a lavish dinner, lots of kissing and hugging and the crisp freshness of white snow, concluded by a booming ‘Merry Christmas!’

This sensory pedagogy is connected, it seems to me, to a deeper history of holidays, in which not just the shared emotional importance and universal value of holidays is highlighted but also an attitude of vigilance towards those outside of the community is instilled. The Christmas movies continue a tradition with roots dating back at least to the Middle Ages. Historically, Easter and Christmas have been (and remain) times in which identification but also othering intensifies. Historians of Judaism have highlighted that holidays were a notoriously unsafe time for Jews.[3] Gavin Langmuir in Toward a Definition of Antisemitism provides numerous examples of how antisemitic stories circulate about alleged hostile behavior of Jews during Christmas.[4] Christmas and Easter pogroms indicated the intensity with which shared identification can lead to intense exclusion.

This history, in which Jews were presented as the enemy of Christmas, resonates with the way in which Christmas movies restage the Christmas script. For instance, an extensive discussion exists whether Ebenezer Scrooge, the money-hungry outsider who needs to be converted through miracles to believe in the message of Christmas, in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is based on antisemitic tropes. Similarly, people have interpreted The Grinch as an incarnation of the stereotype of the Jew that needs to be converted to Christianity.

In short, the intense emphasis on the importance of holidays had (and has) as its corollary, a more intense exclusion of those who are seen as outside of the celebrating community. Both are intensified by sensory experience and public visibility. When we return to our present, it is no surprise (nor, admittedly, a particularly profound insight) that contemporary Christmas scripts reflect concerns, fears and practices of in,- and exclusion of its time. Most contemporary movies obscure the exclusionary effects of Christmas and favor comedic feel-good claims to universal inclusivity, we can also see a rise in downright militant Christmas movies in which new enemies are presented. Particularly in the United States, an increasing amount of highly politicized apocalyptic Christmas movies were released over the past decade or so.

Saving Christmas (2014, the tagline of the movie: ‘Put the Christ Back in Christmas’, see figure 3), presents a disenchanted world in which people are convinced that Christianity has nothing to do with Christmas. The main protagonist schools the other characters (and the audience) by highlighting the importance of the Biblical roots of Christmas. In order to celebrate the saving of Christmas, the cast breaks out in a rather cringy break-dance routine.

A more radical example can be found in Christmas with a Capital C. In this movie we see a Grinch-like atheist (played by Daniel Baldwin) suing a small community, invoking separation of Church and state and political correctness, and force them to take down all Christmas decorations. In the final part of the movie, the kindness of rural America melts the heart of the ardent atheist and, converted, he joins the celebration: ‘a couple of crazy Christians changed my mind’. The image that is sketched is a potential dystopia in which claims concerning ‘equality’ and accusations of discrimination are used to outlaw any public expression of Christianity in general and Christmas in particular. Luckily those who persist in their faith in Christmas will triumph.

Last Ounce of Courage (2012) presents the story of a father of a soldier who died in Iraq. Besides grieving for his son and taking care of his grandson (not coincidentally called ‘Christian’), he has to deal with a culture that takes down Christmas decorations and bans Christianity. The father is angered by the attack on everything his son died for, and leads a Christmas uprising to reclaim the spirit of the United States and to safeguard a future for his grandson. The trailer includes the following lines: ‘Battles have been fought…But the war has just begun….When the Bible Is Outlawed….When the Cross is an Offense…When Christmas is a Crime….Each Person Can Make A Difference.’

Though differing in who or what the enemy of Christmas is, these films follow the script of Christmas movies I outlined above: Christmas is threatened and something needs to happen, enemies need to be defeated or converted, so that the universal goodness of Christmas can take place. Note how, instead of Scrooge, or capitalism, it is now leftist elites, secular humanists and multiculturalists who are attacking Christmas.

Far from being an annual exercise limited to fiction and entertainment, such incarnations of the Christmas script are connected to real-life concerns and actions. One need only look at the way in which Christmas is referenced by Donald Trump, in whose discourse America is presented as under attack from all sides and Trump functions as the one who will safeguard that people will say ‘Merry Christmas’ again. Or, Fox News’ perennial fanning of the flames of a War on Christmas, in which concerned reporting concludes every year that Christianity is under attack in the United States. The Christmas script is part of a galvanizing polarization between God-fearing Americans and godless secular-humanist elites conspiring with enemies of the USA with very real consequences.

In the Netherlands, Christmas movies are a relatively young tradition, starting in the early 21st century. Mirroring a global circulation of American-inspired popularized culture, Dutch cinema started to deliver its own series of Christmas movies in which protagonists need to be reminded about the true meaning of Christmas. The list includes Kruimeltje (1999) in which a working class boy teaches industrialized 1920s Dutch society what compassion is and De Familie Claus (2020) where a boy has to rediscover the true meaning of Christmas after having lost his father on Christmas day.

A Dutch version of the politicized War on Christmas was also on the rise in the 21st century. It has become somewhat of an annual tradition to present Christmas, much like Easter, as a holiday under attack. In 2016, it was reported that a Christmas tree was removed from a Hogeschool in Amsterdam. Allegedly, the school caved in to Islamic demands. In 2017, the public broadcasting company NPO presented its new slogan ‘December Vier je Samen’ (Let’s Celebrate December Together). The absence of Christmas was seen as an attack on Christmas by a politically correct elite afraid to ruffle Islamic feathers. The sustained presence of such controversies in public debates is remarkable. Even when debunked (for instance, the Christmas tree which was allegedly removed from the Hogeschool turns out to have not been removed at all), news reports keep circulating, accompanied by outraged commentary.

In order to get some more grasp on how ‘Christmas’ circulates on social media, I have monitored the use of the hashtag #kerstmis on Twitter. I harvested all Tweets mentioning ‘kerstmis’ since December 1st 2021. The result is a dataset of about 30.000 Tweets of people talking about Christmas. This dataset includes varied things such as advertisements, people sharing pictures of their sweaters, uplifting messages of togetherness and comfort, announcements for concerts and municipalities showing the setting up of Christmas trees. But a sizable chunk, my preliminary labelling suggests about 30%, can be characterized as expressing outrage about attacks on Christmas.

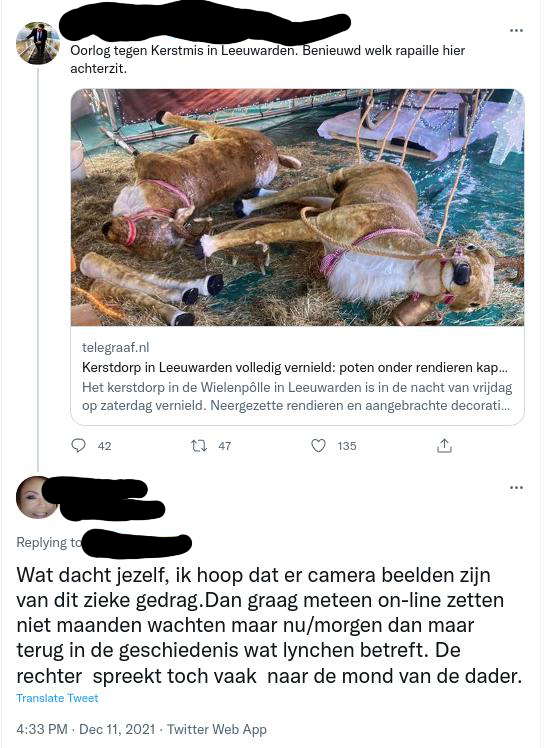

This year, the attacks on Christmas included a Christmas village vandalized in Leeuwarden. Unknown assailants destroyed the mock reindeers in the Christmas village. These news reports are cited on Twitter and accompanied by remarks like ‘Hatred for Christmas and all it means has never been bigger. Our European Commissioner for Equality will be glad’[5] and ‘Islamization and Replacement of the People (‘Omvolking en islamisering’)’[6], or: ‘How great. Let’s bring in more people who ‘celebrate’ Christmas.’[7] A final example (see figure 5):

‘War against Christmas in Leeuwarden. I wonder what kind of scum is behind this.’[8] Responses to this Tweet include speculation about the ethnic, religious and racial background of perpetrators as well as suggestions about what to do with them. One example reads: ‘What do you think? (…) Best to go back in history with regards to lynching. Judges mostly favor the perpetrators nowadays anyway’[9]. Note that at the moment of writing nothing is known about the perpetrators of this act of vandalism.

Another widely circulated news report described a French Christmas procession harassed by, the report indicated, Muslim youths. On Twitter, this report was seen not as an incident but rather a sustained attack on cultural identity of France, and by extension, the West. For instance, Dutch comments included references to migration, terrorism, and the bleak future for Europe: ‘it may take a while, but civil war will come’[10]

A third example is the sustained outrage which was directed to the European Union since the beginning of December. A committee published, and subsequently retracted, a report with suggestions for guidelines on ‘inclusive language’ in which a suggestion was made to use the phrase ‘Happy Holidays’ instead of Merry Christmas. This was (and at the moment of writing, remains) for the detractors of the report an example of how the ‘elites’ of the European Union are part of an attack on Europe’s identity: ‘it is a slippery slope: remove Christian origins from society and let other cultures and religions have more influence’[11].

A script keeps returning: ‘Christmas’ functions in these examples as a symbol for an embattled sense of identity. Christmas is presented as universally good, as a marker of identity, and as perpetually under attack. And, so the script goes, action is needed to save Christmas (and therefore ourselves) before it is too late.

The biggest source of outrage involves Corona-measures. Measures that limit the amount of visitors people are allowed to have in their home, limiting Christmas markets, concerts and church services to take place, such measures are interpreted as an outright attack on Christmas and therefore on ‘the people’. For instance, a short clip showing German police arresting a Santa Claus in a German town (see figure 6) is frequently shared with interpretations of the incident: ‘Christmas is cancelled this year. Covid fascism’, ‘Now they want to destroy Christmas too.’[12] People debate whether the injunction not to visit grandmother and grandfather runs counter to the Christmas message: ‘are we still celebrating the birth of the man who, against all advice, went to visit the ill?’

Of course, this is not all there is. There are also initiatives that interpret the script of Christmas in a less politically engaged sense. Take for instance initiatives like #Qrstmis (see figure 7). This initiative, launched by the Dominicus church in Amsterdam and supported by a number of other churches, aims to steer Christmas away from Corona-related outrage: ‘Not Christmas, but rules and outrage sets the tone during this second Corona winter (…) This Christmas, let us fight somberness and polarization in this time of darkness.’[13] This initiative explicitly uses the script of Christmas (including its combative side) to combat loneliness, which seems a more abstract enemy than, say, Muslims, multiculturalists or the minister of Health, Welfare and Sport.

‘Christmas’ remains a powerful script that circulates in many forms. It shows how the script of an embattled Christmas can be used to interpret current affairs, to fuel emotion, and how the season to be jolly is also the season to be outraged. As holidays have the tendency to become ‘naturalized’ as seemingly self-evident expressions and self-congratulatory celebrations of communities (and dehumanization of its outsiders), it is also the season to be careful.

Ernst van den Hemel (1981) is a scholar of religious studies and literature. He is a researcher at the Meertens institute, where he works on a new research project on populism, religion and social media (click here). His book Passie voor de Passie. De Matthäus, The Passion en andere passiespelen in ontkerkelijkt Nederland (Utrecht: Ten Have, 2020), appeared this month as the new-year-book of the Meertens institute (link). This publication was written as part of the HERA research project HERILIGION (link).

See also “Of Pandemics and Passions: Virtual Choirs and Collective Healings” (Religious Matters, April 2020).

References

[1] I wrote this blogpost whilst in quarantine. Warning for the reader: I spent isolation perhaps watching a few too many outrageous Christmas movies and a few too many sordid Twitter discussions. Please do not see this as one of those ‘10 best Christmas movies’ listicles and excuse any excess cynicism. Also, thanks to Niels ten Oever for brainstorming the title with me.

[2] In reference to Bonno Thoden van Velzen, Irene Stengs uses the notion ‘script’ to describe how pre-existing scenarios are used to make sense of current affairs. This way, collective imaginations, fears and desire take shape in the present. See Stengs 2018, p.6.

[3] Scholars have described a series of traditions developed in European and American Judaism to pass Christmastime safely. This often involved inconspicuous activities like playing card games at home, leaving the lights off, abstaining from reading Torah, or eating Chinese food.

[4] See Gavin Langmuir’s Toward a Definition of Antisemitism, p.264.

[5] https://twitter.com/UnpleasantTrut2/status/1470074324757397512[6] https://twitter.com/lewinskylou2/status/1469818041894686725

[7] https://twitter.com/Shikra145/status/1469971036661862401

[8] https://twitter.com/baspaternotte/status/1469689429216354313

[9] https://twitter.com/LilyvL/status/1469691745717923847

[10] https://twitter.com/_Je_Suis_Bella_/status/1470848298831466496

[11] https://twitter.com/jpgk66/status/1469948503505965057

[12] https://twitter.com/HenriOsewoudt/status/1470740433810735109

[13] https://qrstmis.nl/