From 27 January until 4 February 2023, Birgit Meyer, Lucien van Liere and myself went on a brief trip to Kenya to participate in two research seminars and present and discuss the insights of my PhD thesis. The first was held at Pwani University in Kilifi, where Birgit Meyer gave a lecture entitled Studying Religion in and from Africa, and I gave a presentation on my PhD thesis, entitled ‘Regulating Religious Coexistence, the Intricacies of ‘Interfaith’ Cooperation in Coastal Kenya, which I defended on June 15, 2021. The seminar was kindly hosted by Dr Ali Awadh and Dr Tsawe-Munga Chidongo from the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies and was open to all staff and students from Pwani University. The second seminar took place at St. Paul’s University in Limuru, where Lucien van Liere presented on Studying Religion and Violence and I gave a lecture on my PhD research again. This seminar was kindly hosted by Dean Dr Julius Kithinji and Rev Ven Scholar Kiilu and was open to all students of the MA program Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations (ICMR) and staff of St. Paul’s University. During my PhD research, I have received tremendous support from scholars from both Pwani University and St. Paul’s University, without which it would have been impossible to do my work. Consequently, I am grateful to these institutions for hosting us once again, and taking an interest in our work.

The research team from Utrecht together with staff and students from St. Paul’s University

The research team from Utrecht together with MADCA members, guests, and university staff during the seminar at Pwani University

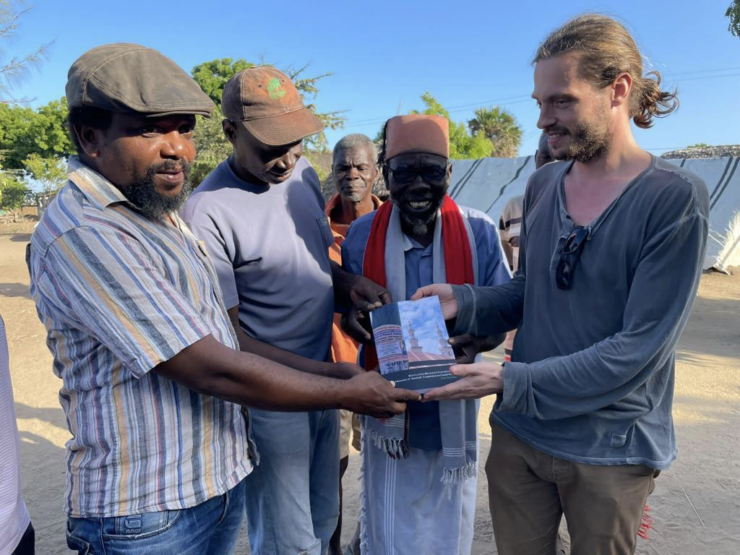

This visit to Kenya also gave me the opportunity to reconnect with many of my research interlocutors with whom I interacted during my PhD research on religious coexistence in the coastal Kenyan town of Malindi and to introduce my former PhD supervisors to the setting in which I conducted my research. One of the groups to which I reconnected is the Malindi District Cultural Association (MADCA), an organization that wants to promote the culture and religion of the Giriama people, many of whom live in Malindi and its rural environs. In their cultural centre a few kilometers outside of Malindi, MADCA displays several important aspects of Giriama tradition, such as traditional houses, and vigango, which are wooden posts that represent deceased ancestors who belong to the Gohu society and allow Giriama people to interact with those who have passed away. While we were received at the cultural centre of MADCA, several Giriama elders shared with us how the cultural centre also functions as a place of refuge for elders who are accused of practicing witchcraft and have to fear for their lives, as the relatives who accuse them may try to injure or kill them.

Erik Meinema hands over his dissertation to MADCA members at their cultural centre

To properly understand the predicament in which these elders find themselves, it is useful to reflect on the history of religious coexistence in the coastal region of Kenya, which is significantly shaped by what Ali A. Mazrui (1986) has called the ‘triple heritage’ of African traditions, Islam, and the West. Islam has a history of more than a millennium in coastal Kenya, and Christianity has made a significant impact particularly since British colonial times (1895-1963). Next to Swahili Muslims and Christians who often find their origins in ‘upcountry’ parts of Kenya, coastal Kenya is also inhabited by other coastal populations such as the Giriama. Although several Giriama have become Christians and some also Muslims, many Giriama continue to practice and identify themselves with indigenous Giriama culture and religion.

Coastal Kenya is, however, also a region in which Muslims, Christians, and state actors have often denigrated and demonized the Giriama and their indigenous African culture and religion, or have associated it with ‘backwardness’, ‘idolatry’, and ‘witchcraft’. The roots of such ideas often go back to colonial times, in which British rulers used English terms such as ‘religion’, ‘culture’, ‘tradition’, and ‘witchcraft’ to describe and categorize African ideas and practices, based on their own frames of reference and their own presuppositions about the supposed meaning of such terms (see also Meinema 2021). The term witchcraft found its roots in both theological and scientific understandings that found their origins in Europe. In theological understandings, for example, the term witchcraft was closely associated with the Devil and heresy. Such perspectives were originally developed during the European witch-hunts in the late 15th century by Roman-Catholic theologians in publications such as the Malleus Maleficarum, but later also adopted by Protestant missionaries who worked on the African continent. In line with European understandings of ‘witchcraft’, these missionaries understood African ideas and practices that were categorized as ‘witchcraft’ to be dangerous and demonic. At the same time, early scholars of religion such as E.B. Tylor and J.G. Frazer saw ‘magic’ and ‘witchcraft’ as irrational and a form of ‘primitive superstition’, and an evolutionary predecessor to supposedly more advanced and rational forms of religion such as Christianity. Given these theological and scholarly backgrounds, the term witchcraft carried strong associations with the primitive, irrational, and demonic.

The theological and scientific roots of the term witchcraft also made that British colonial officers often shifted back and forth between two different ways in which they understood African ideas and practices that they categorized under the label witchcraft. On the one hand, they saw such ideas and practices as an expression of African ‘primitiveness’ and ‘superstition’, which they expected to disappear when Africans would modernize and develop. Such lines of reasoning also inform the Witchcraft Act that was introduced in colonial Kenya in 1925, which criminalizes those who ‘pretend (emphasis added) to exercise or use any kind of supernatural power, witchcraft, sorcery or enchantment’, as the law formally does not recognize that witchcraft exists and can be actually practiced (see Waller 2003, 245). On the other hand, however, British administrators sometimes recognized the spiritual powers of witchcraft, which they considered to be dangerous. They did so when they used the term witchcraft to describe African movements that challenged British rule, such as the Giriama uprising of 1913 or the Mau Mau movement that violently resisted British settler colonialism in central parts of Kenya during the 1950s.

In coastal Kenyan society today, we can detect similar patterns in which ‘witchcraft’ is alternatively understood as irrational, but sometimes also as a spiritual danger. After Independence, the Witchcraft Act of 1925 was incorporated into the Penal Code of Kenya with only minor changes, and continues to criminalize those ‘pretending to exercise witchcraft’. While this phrasing suggests that the Penal Code does not acknowledge the existence of witchcraft, many Pentecostal Christians in Malindi do recognize the spiritual potential of African religious traditions, but understand this power as the result of the work of the Devil. Consequently, Pentecostal Christians tend to associate African traditions as a whole with ‘witchcraft’ and the Devil. Many reformist-oriented Muslims similarly distance themselves from African ideas and practices, which would allegedly lead to the acceptance of ‘witchcraft beliefs’, but also to apostasy (shirk), because these practices draw on spiritual forces and entities other than Allah.

Many Giriama in Malindi also recognize the spiritual potential of African religious traditions. Many Giriama ritual practitioners are referred to as aganga – a term often translated into English as ‘traditional healers’ by those who use their services and, derogatively, as ‘witchdoctors’ by those who reject them. Yet, Giriama thought recognizes that ritual practices and spiritual powers can be used for both beneficial ends such as healing (uganga), and for malicious ends such as hurting or killing others. In Giriama thought, such malicious use of spiritual powers would be classified as utsai, a term often translated to English as ‘witchcraft’. Thus, while reformist-oriented Muslims and Pentecostal Christians tend to associate all aspects of African traditions with ‘witchcraft’ or idolatry, and reject them altogether, many Giriama people recognize that ritual practices and spiritual powers can be used for both positive goals (uganga) and malicious ends (utsai). In this logic, traditional healing (uganga) can be employed to counter witchcraft (utsai).

It is in this context that we can try to understand the complex situation in which Giriama elders who are accused of practicing witchcraft find themselves. During my fieldwork, I heard stories on various occasions about Giriama youth who accuse older relatives of practising witchcraft (utsai) against them, after which they chase them away or kill them. According to many interlocutors, youth who accuse elders of practicing witchcraft have clear economic incentives to do so, because killing or chasing away elders makes it possible for them to inherit plots of land and other family possessions. Selling off these plots would enable youths to look for ways to economically sustain themselves in a context that suffers very high unemployment rates, for example by buying a motorcycle which they can use to provide motorcycle taxi services. Such stories suggest that witchcraft accusations are closely connected with intergenerational tensions and conflicts over family resources, in which witchcraft accusations offer youths a vocabulary to both understand these tensions and to catalyse and intervene in conflicts in a violent manner.

The common occurrence of violence against elders following witchcraft accusations has led the County Government of Kilifi, in which Malindi is situated, to initiate a public campaign that uses the slogan ‘uzee sio uchawi’ (‘old age is not witchcraft’). Like the Witchcraft Act, this slogan also suggests that the government does not entertain the possibility that witchcraft actually exists. It merely discourages people to see any connection between old age and witchcraft and to make accusations against elderly relatives. During my previous research, some of my interlocutors also argued that attempts by the state to halt witchcraft-related violence were complicated by the Witchcraft Act. They explained that this act makes it difficult to prosecute those who are suspected of practicing witchcraft because courts require tangible evidence for a crime that the law does not recognize to exist. Furthermore, the Witchcraft Act also criminalizes accusing another person of practicing witchcraft unless a government official such as a District Commissioner or police officer is present, or attempts to identify criminals (such as those who allegedly practice witchcraft) via ‘non-natural means’. This means that courts would find it difficult to recognize – and may even criminalize – attempts by, for example, Giriama ritual practitioners (aganga) to identify those who allegedly practice witchcraft and provide ritual solutions for it. According to law scholar Katherine Luongo (2008), this situation makes it nearly impossible to settle witchcraft accusations via courts. In this situation, people who fear bewitchment sometimes resort to violence vis-à-vis the presumed witches to settle suspicions. This problem has challenged government authorities since colonial times, and currently also threatens elders in and around Malindi who are accused of practicing witchcraft.

As an alternative, some Giriama elders propose that the government should cooperate with Giriama practitioners to identify those who practice witchcraft and to provide ritual solutions to it. These elders argue that such traditional methods to deal with witchcraft accusations rarely resulted in violence, because identified witches had to compensate the damage they allegedly caused and had to swear oaths to never practice witchcraft again. Many government officials are reluctant to engage in such cooperation. This is perhaps unsurprising, as seeking ritual solutions for witchcraft presupposes that witchcraft actually exists, which contrasts with state laws such as the Witchcraft Act. Furthermore, many government officials continue to distance themselves from the belief in witchcraft, which they see as ‘backward’ and ‘primitive’. It also remains to be seen whether such solutions would be accepted by all Giriama youth, because attempts to find ritual solutions to witchcraft by ritual practitioners (who often belong to older generations) do not necessarily resolve existing generational tensions between Giriama elders and youth, some of whom continue to suspect Giriama elders of practising witchcraft against them.

It is in this complicated context that MADCA operates its cultural centre that doubles as a ‘rescue centre’ for elders who are accused of practicing witchcraft. Providing refuge to accused elders in a centre that promotes Giriama culture and religion may raise questions and/or suspicions among Christians and Muslims who associate Giriama tradition with ‘witchcraft’ altogether, or among people who fear that the accusations that are levelled against elders may hold truth. During our visit to MADCA, members explained that they try to convince others of the necessity of protecting elders through an emphasis on the humanity that these elders share with neighbours from diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds, regardless of whether one believes in the existence of witchcraft or not. In this way, MADCA stands in a longer tradition in which the Swahili term utu (humanity) – which has both descriptive and normative qualities (see: Kresse 2007, 139-151) – is invoked in the coastal region of Kenya as a framework to foster social bonds across ethnic and religious divides. Through this emphasis on a shared humanity, MADCA also appeals to other civil society organisations and the government to aid in the provision of shelter, food, and protection to accused elders, because in MADCA’s view, as human beings they have a right to security and basic necessities in life, whether they have practiced witchcraft in the eyes of some or not.

References

Kresse, Kai. 2007. Philosophizing in Mombasa: Knowledge, Islam and Intellectual Practice on the Swahili Coast. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press for the International African Institute.

Luongo, Katherine. 2008. “Motive Rather than Means. Legal Genealogies of Witch-Killing Cases in Kenya.” Cahiers d’Études Africaines, XLVIII (1-2): 189-90, 35-57.

Mazrui, A. A. (1986). The Africans: A Triple Heritage. BBC Publications.

Meinema, Erik. 2021. Is Giriama Traditionalism a Religion? Negotiating Indigenous African Religiosity in ‘Interfaith’ Cooperation in Coastal Kenya, Journal of Religion in Africa, 50(3-4), 344-72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/15700666-12340196.

Waller, Richard D. 2003. “Witchcraft and Colonial Law in Kenya.” Past & Present 180: 241-75.