Liana Chua (Brunel University London)

As COVID-19 began to spread across Malaysia in early-2020, Jesus began to materialise with increasing frequency on my Facebook feed. A familiar figure with light skin, beard, long hair, and flowing robes, He appeared in many classic poses: praying, healing the sick, carrying a cross, crucified. Overlaid onto these images, however, were references to a disease that we have only recently come to know: “COVID: Christ Over Infection, Virus and Death”; “JESUS is the best doctor and prayer is the best medicine”; “Harapan di Tengah Coronavirus! Tuhan Yesus Sayang Kita Semua” (“Hope in the midst of Coronavirus! Jesus loves us all”).

COVID-19 related messages are part of a diverse assemblage of Christian posts that have been circulating on the Facebook networks of my fieldwork acquaintances: indigenous Bidayuhs in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, with whom I’ve worked since 2003. Many are second- or third-generation Christians who live in villages and work or study in urban areas. Multilingual, mobile and tech-savvy, they treat digital interaction as intrinsic to their religious lives—partly by following and sharing material from international Christian interest groups on Facebook, which is used by Bidayuhs of all ages.

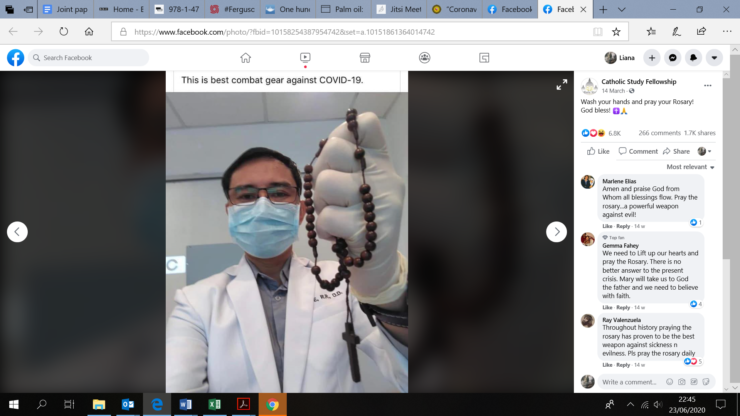

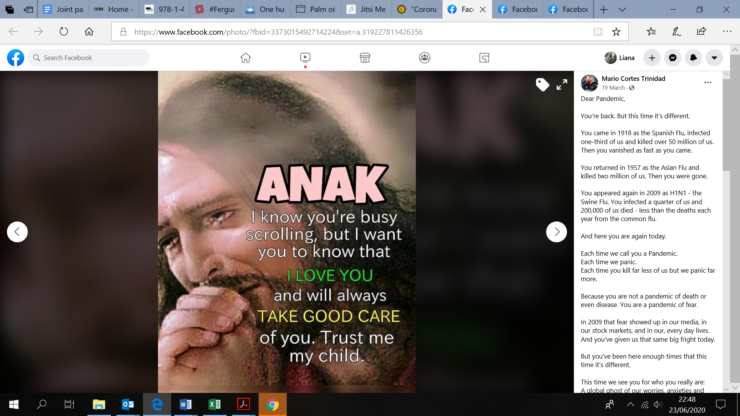

When COVID-19 first reached Malaysia, many Facebook exchanges sought to frame the virus through Christian terms and idioms. Although there were attempts to relate the pandemic to the Apocalypse, most of my acquaintances seemed more keen to work out COVID-19’s implications for their religious faith and praxis. The most popular posts combined biomedical tropes with those of “visual piety” (Morgan 1999): a masked medical practitioner with a rosary (Figure 1), Jesus praying in the Garden of Gethsemane with a list of earlier pandemics and instructions for “turn[ing] viral fright into viral fight” through prayers and hand-washing, among other things (Figure 2). Others embedded the pandemic and its effects in Christian stories and teleological frameworks. A post about how Noah and his family endured forty days of isolation in their ark, for example, became especially popular when Malaysia imposed its own “lockdown”, aka the Movement Control Order (MCO), in late-March. “Like Noah, let us also believe that these things shall pass,” it concluded. “Stay in the ark, stay at home”.

one biomedical, the other religious (source).

previous pandemics. “Anak” means “child” in Bahasa Malaysia and other regional languages (source).

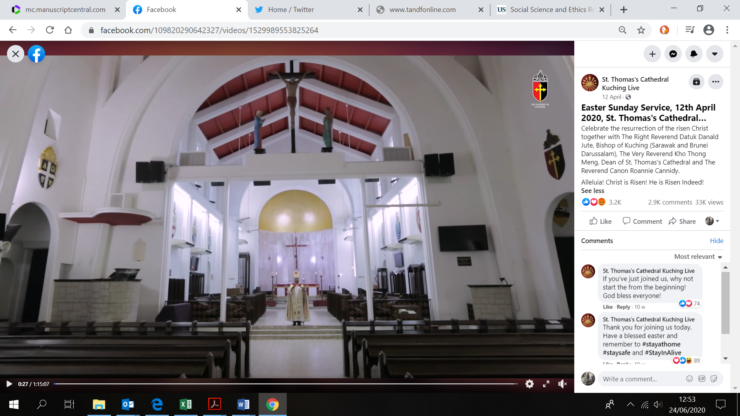

As March segued into April, motivational messages gave way to pragmatic concerns about participation, particularly during Holy Week, which fell in mid-April. For many of my acquaintances, being Bidayuh is synonymous with being Christian—an identity which, in a Malay-Muslim majority country, is both politically and socially laden (Chua 2012). Like Christmas, Easter a crucial time in the village calendar: when Bidayuhs return from town to be with friends and family, when village chapels and rural parish churches are packed with worshippers, and when everyone eats, drinks and celebrates together in an idealised affective, spiritual and physical state known as rami. In short, Easter is when Bidayuhs come together as Christians, and reaffirm their identities and place in a global Christian oecumene that transcends the confines of the Malaysian nation-state (Figure 3).

Paschal flame up to the village chapel at the start of the Easter Vigil on Holy Saturday (April 2010).

This year, however, there was none of that. “Stay at home” became a mantra that my friends drearily repeated as they explained why they couldn’t hold their usual prayer services and gatherings. In the run-up to Easter, questions of how to be Christian and do Christian things while distanced from the sites, entities, and people that constitute Christian life took on increasing urgency. In this gloomy climate, churches—like their counterparts elsewhere (e.g. Dijkstra 2020; Sheklian 2020)—rallied, shifting their services online (Figure 4). At first, they posted live or recorded footage of prayer services on YouTube or Facebook, but they soon began to make things more participatory. The Catholic parish church nearest my adoptive village, for example, posted on its Facebook page step-by-step instructions for following its services online—including a list of technical requirements, a guide to setting up a home altar, directives for how to dress and behave during the service, and advice on how to transfer one’s weekly offertory money into the archdiocese’s bank account. Later, it invited parishioners to add photos of their home altars to a dedicated album (Figure 5) and submit prayer requests via private messaging.

Easter Sunday service on Facebook (12 April 2020 – source).

home altar setups (April 2020 – source).

Although rural access to these online initiatives varied greatly due to patchy internet coverage, these digital interactions worked as well as they could in the circumstances. As I followed live services from locked-down England, my screen would be filled with dancing emojis and “Amens” from my fellow viewers, some of them my village acquaintances. There was a certain “collective effervescence” (Durkheim 1995) in these moments—one quite distinct yet palpably familiar, the text and icons replacing yet not displacing that affective surge of physical togetherness.

***

These forms of digital religious participation were in many ways new and makeshift, products of an extraordinary moment in which Christian life juddered to an upsetting halt. But in other ways, they were simply extensions of a quotidian set of religious practices that straddle the online/offline divide. Praxis and efficacy are key to the day-to-day workings of Bidayuh Christianity, which is viewed as something that needs to be “done” (ndai) right (Chua 2012). When smartphones and Facebook became incorporated into everyday village life, my acquaintances extended their Christian praxis online, adapting quickly to the wider global Christian social media-scape’s prevailing terms and conventions. Today, with both churches and individual congregants active on Facebook, social media interactions form a “legitimized frame” (Bielo 2018:371) of Christian interaction and experience for Bidayuhs—no less valid or meaningful than their fleshly equivalents.

Posts, comments, and shares on Facebook are often about making one’s presence felt, publicly reaffirming one’s faith and commitment, and caring for others. Posts about deaths, illnesses, birthdays, journeys and other events, for example, are often followed by formulaic strings of comments: “RIP”, “Tǎpa rǎbis sayang ayǔh” (God loved them [the deceased] more), “MGBU” (“May God Bless You”), and most commonly, “Amen”. These threads are, in effect, manifestations of what Miller et al. call “scalable sociality” (2016:109)—digital instantiations but also transformations of relations that criss-cross and spill beyond village communities, coexisting alongside Facebook sociality. Just as some villagers sleep over at newly-bereaved houses to keep the family company, guard their souls, and stop them feeling afraid (Chua 2011), these digital interjections are momentary enactments of presence: reassurances that we are here for you.

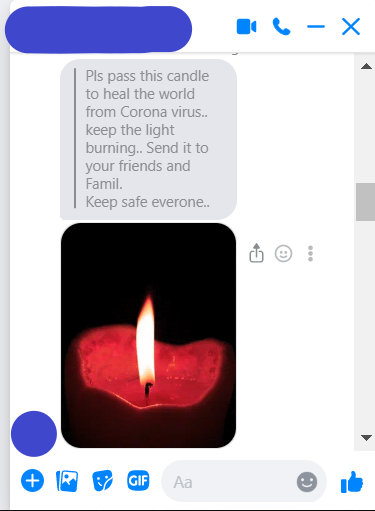

Such interactions often play on the viral affordances of social media (Coates 2017; Postill 2014). For example, the start of the pandemic saw a rush of people typing or copy-and-pasting the Lord’s Prayer onto their timelines, together with injunctions such as “Copy to your profile, let’s all pray together”. Some posted customised instructions for reciting the rosary during the pandemic—each decade punctuated by prayers for hope and healing. Meanwhile, several users changed their profile pictures to devotional images, notably a lit candle bearing the image of Christ healing the sick, for the duration of the MCO. Also circulating via private messaging were GIFs of candles, with the invitation to “pass this candle to heal with world from Corona virus…keep the light burning” (Figure 6).

Typing out the Lord’s Prayer, reciting the rosary, “passing on” a candle: these are acts that demand more than a quick click on the “share” button. It is in these acts of consciously, purposefully doing and sharing, I suggest, that my acquaintances locate themselves in a wider Christian world-order—one in which God, Jesus, and other powerful personages are as active and agentive as the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Although social media interactions cannot replace the corporeal togetherness and spiritual efficacy of in-person prayer attendance, they do work alongside them as small-scale, quotidian means through which Christians sustain their relations with each other and the divine in an era of social distancing.

***

Anthropologists of religion will find many of these practices and tropes familiar—and for good reason. As mentioned earlier, my Bidayuh acquaintances use Facebook to participate in Christian interest groups and access posts from across the world, which they then disseminate and personalise via their own networks. Some are denomination-specific, but many consciously transcend denominational differences, enabling Catholics, Anglicans, and evangelicals alike to engage in digital communion beyond their church circles and countries. This combination of circulation and participation, I suggest, entails a form of viral devotionality through which a digitally-mediated mode of global Christian solidarity and spiritual unity can be enacted—individually and collectively.

Put differently, Facebook interactions haven’t simply lent spiritual meaning to the pandemic, nor merely given Bidayuhs a practical means of sustaining Christian practice, sociality, and relations. Such interactions have also enabled Bidayuhs to insert themselves into a digital landscape of devotional acts and viral trails, as self-consciously globalised Christians belonging to a larger oecumene that transcends the Malaysian nation-state. Bidayuh Christians have long been conscious of their place in the worldwide Christian community: prayers for the Pope and for persecuted Christians elsewhere, for example, featured regularly in rural chapel services well before the arrival of mobile phone reception and internet access. But the COVID-19 pandemic has both amplified this conviction and multiplied the opportunities for actualising it. For a marginalised indigenous community that routinely looks beyond national borders for social, moral, and cosmological support, these are not insignificant digital openings.

In contrast to the destructive virulence of SARS-CoV-2, then, my acquaintances’ interactions with and through Christian/COVID-19 Facebook posts entail an aspirational and generative virality—their digital exchanges serving as portals to larger spaces of Christian commonality, belonging, and divine power. Thinking through these engagements can prompt us to ask broader, comparative questions: What other kinds of virality are emerging or evolving in the present? What practices and imaginaries of connection, solidarity, and commons are they producing, and to what effect? How might anthropologists think with, but also beyond, extant analytics of virality in medical and digital anthropology (e.g. Benton 2017)? And, crucially, how can virality be understood as productive and creative rather than mainly destructive or something to be avoided?

These questions will arguably become more pressing as the world lurches towards various possible “post-COVID” futures. Anthropologists and other scholars have recently done a great deal to dismantle the banal, pervasive trope of COVID-19 as the great leveller, showing how the global pandemic has played out in multiple, uneven ways, laying bare vast global and national inequalities in the process. Challenging hegemonic “commoning” (Blaser and de la Cadena 2017) narratives and politics is, after all, our stock-in-trade. Yet amid all this, the intensification of my Bidayuh acquaintances’ digital engagements with a global Christian commons reminds us not to lose sight of the small-scale, quotidian projects of commonality, solidarity, affinity and uniformity that are also emerging in the pandemic: what they are, how they work, how they are socially, historically, and politically grounded, and perhaps most challengingly, what they might look like beyond the horizons of the immediate crisis. How do we make and sustain connections across closed-off borders, quarantined spaces, social distances? How can we forge commonality and unity out, or in spite, of difference? And how can we ground or actualise such possibilities rather than simply theorise or speculate about them? As we come to terms with the need to live with, not just contain or eradicate, SARS-CoV-2, these are questions with which anthropologists are likely to grapple for a while.

Bionote

Liana Chua is a social anthropologist based at Brunel University London. She has worked on Christian conversion, ethnic politics, development, displacement and environmental change in Malaysian Borneo since 2003, and currently leads the ERC-funded research project, Refiguring Conservation in/for ‘the Anthropocene’: the Global Lives of the Orangutan (2018-23).

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.

References

Benton, Adia. 2017. “Ebola at a Distance: A Pathographic Account of Anthropology’s Relevance”. Anthropological Quarterly 90 (2): 501-530.

Bielo, James S. 2018. “Flower, Soil, Water, Stone: Biblical Landscape Items and Protestant Materiality”. Journal of Material Culture 23 (3): 368–387.

Blaser, Mario and de la Cadena. 2017. “The Uncommons: an Introduction”. Anthropologica 59:185-193.

Chua, Liana. 2012. The Christianity of culture: Conversion, ethnic citizenship and the matter of religion in Malaysian Borneo. New York: Palgrave Macmillan Contemporary Anthropology of Religion series.

—2011. “Soul Encounters: Emotions, Corporeality, and the Matter of Belief in a Bornean Village”. Social Analysis 55 (3): 1-17.

Coates, Jamie. 2017. “So Hot Right Now: Reflections on Virality and Sociality from Transnational Digital China”. Digital Culture and Society 3 (2): 77-98.

Dijkstra, Veerle. 2020. “Going Online: How Corona Transforms Christian Worship”. Religious Matters in an Entangled World blog, 6 May 2020. Weblink (Dossier Corona).

Durkheim, Émile. 1965 [1912]. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life,trans. Karen Fields. New York: Free Press.

Miller, Daniel, Elisabetta Costa, Nell Haynes, Tom McDonald, Razvan Nicolescu, Jolynna Sinanan, Juliano Spyer, Shriram Venkatraman and Xinyuan Wang. 2016. How the World Changed Social Media. London: UCL Press.

Morgan, David. 1999. Protestants and Pictures: Religion, Visual Culture, and the Age of American Mass Production. New York: Oxford University Press.

Postill, John. 2014. “Democracy in an Age of Viral Reality: A Media Epidemiography of Spain’s Indignados Movement”. Ethnography 15 (1): 51-69.

Sheklian, Christopher. 2020. “Communion in Quarantine: How Liturgical Christian Churches Celebrated Easter”. Covid-19, Fieldsights, 28 April 2020. Weblink.