Igor Jurekovič

The discussion of “offensive” images in societies marked by cultural and religious pluralism gives rise to poignant questions related to conflicts such as those pertaining to the Muhammad cartoons: Are there objectively offensive images out there? If so, how do we know which images are outright offensive and which are “merely” so subjectively? Does the intention of the author matter? What normative structures should be in place in a contemporary plural society to both protect religious sensitivities, especially those of often discriminated religious minorities, and the democratic freedom of speech?

However, it would be erroneous to assume that all controversies regarding ‘offensive’ images involve religious minorities. Dwelling on the offensive potentiality of images took an interesting turn with this year’s legal controversy over the trademarked Jägermeister logo in Switzerland. While seemingly fitting in well with contemporary scholarly discussions on the potentiality of offensive images, the controversy raises an additional question regarding religious images in a secular setting: can powerful (religious) images be weakened? If so, how?

The story behind the image

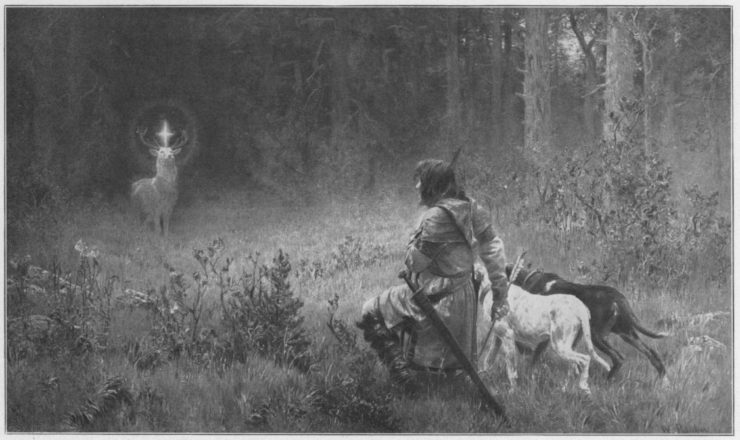

Before discussing the legal controversy, let us first delineate the history of the “problematic” logo. While the shape and the form has changed over the years, the central image remained – the stag with a shining white cross between its antlers. The motif is taken from the legendary conversion story of Saint Hubertus or Hubert (656–727). According to The Catholic Encyclopaedia (Brown 1910), on a Good Friday morning, Hubert opted for hunting instead of attending service at a local church. Pursuing a stag, the animal suddenly turned and, according to the legend, Hubert saw a shining crucifix standing between stag’s antlers (Fig. 1), while hearing a voice say: “Hubert, unless thou turns to the Lord, and leadest an holy life, thou shalt quickly go down into Hell”. During the vision, Hubert was instructed on how to treat game fairly, with the voice ending on telling Hubert to seek Lambert, who was a bishop in Maastricht. Following his guidance, Hubert became ordained and – with the death of Bishop Lambert – was named the bishop of Tongern in 705, though he moved his official residence to Liege in 717, where he died on 30 May 727. He became Saint Hubert of Liege, a patron of archers, dogs, forest workers and huntsmen. He was widely venerated during the Middle Ages (Fig. 2).

However, the Christian motif of Saint Hubert has since 1935 been appropriated and trademarked by the German alcoholic beverage company Jägermeister in various versions (Fig. 3). With the term Jägermeister being a common German label for foresters and gamekeepers, the appropriation of the aforementioned Christian tale seemed to be a commercially sound decision – by evoking the cultural past in the commercial present, it grabs the attention of the onlooker. Indeed, the company does not shy away from its logo’s Christian past, describing the “awe-inspired” Hubertus, who recognized the “glowing cross enthroned between [white stag’s] antlers” as “a sign from God” (Jägermeister 2020), acknowledging Hubertus as the patron saint of hunters.

Nevertheless, the Jägermeister company leaves itself open to criticism of offending Christian sensitivities by adopting and trademarking the Hubertus stag, which “has graced the front label of the distinctive, green Jägermeister bottle since 1935” (Ibid).

Weakened powerful images?

The latest controversy surrounding the logo began with the Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property blocking Jägermeister’s attempts to expand its trademark to entertainment and cosmetics (Swissinfo 2020). The Swiss institution demanded a restriction on the company’s widescale use of its logo – particularly the crucifix – claiming the image was offensive to the religious sensitivities of some consumers. Fighting back, the German company went to court. The Federal Administrative Court in St. Gallen rejected the restriction on Jägermeister’s use of its logo, stating that it can be used as a promotional, commercial symbol in Switzerland. Interestingly, in the context of discussing potentially offensive images, the Swiss federal judges acknowledged the logo’s Christian origin, however they claimed that the “intensive” use of the image had “weakened its religious character” over time, thus making it impossible for it to be offensive to the Christian consumer. According to the ruling, the company can use the logo freely for any commercial activity in Switzerland, including cosmetics, mobile phones or telecommunications services (BBC 2020).

There seems to be an interesting theme developed through this particular controversy – the notion of a weakened religious (and thus, offensive) character of an image. Firstly, the logo fits well in Christiane Kruse’s (2018) discussion on the question of offensive images. In her contribution to the Taking Offense. Religion, Art, and Visual Culture in Plural Configurations (2018), she refers to the famous painting The Holy Virgin Mary by Chris Ofili, the Christ-like image of Thomas Neuwirth, alias Conchita Wurst, and the billboard political campaign of the German Christian Democratic Party, showing a pair of Angela Merkel’s hands poised in a diamond formation (Ibid, 42). Referencing these images of contemporary popular culture, the author underscores the vital importance of pictures of “the old world” of Catholicism – the Madonna icon, the Christ icon and the devotional picture – to ponder the power of contemporary images. Kruse argues that the contemporary examples she chose draw their power (and potential offensiveness) from the Catholic old world, now shown in “the profane space of a Western world that presents itself as secularized” (Kruse 2018, 50–51). Thus, the images become offensive to those who see their original models caricatured in the present.

Adding to the discussion on offensive images, Christoph Baumgartner claims in his own contribution to the aforementioned volume (2018, 335–336) that the offensive potential will be realized by those observes, who are particularly invested in the imagery, thus triggering a powerful reaction. Building on the notion of volitional necessities(Frankfurt, 2003), Baumgartner argues for the impossibility of avoiding powerful reaction by the deeply invested observer. Some images are inevitably offensive to some observers, regardless of any notion of intentionality on the behalf of the author, the image or the observer. The lack of first-hand accounts notwithstanding, Kruse’s and Baumgartner’s observations can be applied to the Jägermeister logo. Within a secular, commercial setting, the picture (the logo) nevertheless carries a clear pictorial form of the old world of Catholic Christianity. As such, the logo can be both understood as another example of merged worlds of an old powerful picture and new, “weak” media pictures (Kruse 2018, 52), and as an example of powerful “offensive” images that inevitably trigger a powerful response.

However, this is not the end of the story. If we are to follow the court’s ruling, the mass commercialization – the intense usage – of the image has weakened its influence, the logo has stopped conveying the canon of Christian ethical values. How are we to understand this in the light of Kruse’s and Baumgartner’s contribution? Can the court’s ruling be simply brushed aside as incomplete in its understanding of offensive images? Or does intensive usage indeed weaken the power of an image? For the sake of the argument, I will assume the latter. The question then is, how is a powerful image weakened? If we accept Baumgartner’s thesis that the offensive potential is (always) there, yet it needs to be triggered by a particular onlooker, do we understand the potential as curbed only by the observer? Or can the transformation of the picture (Fig 3) and the type of its use limit its potential offensiveness as well? Both seem plausible.

On the one hand, the more the modern, “secularized” Christian onlooker detaches herself/himself from its traditional pictorial forms – such as the St. Hubert – smaller is the chance of her/him being offended by it. However, the logo is clearly marked by the most apparent marker of Christianity – the crucifix. It is unlikely that a Christian onlooker would overlook that. It would be absurd for the court to speak of Christians being unlikely to recognize a Christian marker in the logo. On the contrary, the court claims that consumers do recognize the Christian heritage, yet, in this specific setting, the intensive use of the image made it blend in among other commercial logos. In other words, we could say that the potential offensiveness (Baumgartner 2018) is triggered according to the shock value of the picture. The shock comes with a temporal and spatial dimension. On the one hand, the crucifix is not offensive in a sacred setting, while it clearly can be in a secular setting (as Kruse explains drawing on her three examples). On the other hand, the intense usage that marks the temporal dimension, with the St. Hubert’s motif surviving for decades and Jägermeister prospering as a world-renowned beverage, seems to lessen the offensive potentiality.

Consequently, this would then imply that people learn to live with potentially offensive pictures, lessening the “volitional necessity” of being offended. Adding the notion of shock may further develop Baumgartner’s notion of the potential to offend that offensive pictures carry. Furthermore, the notion of people learning to live with potentially offensive images can have important consequences for the debates on normative structures of contemporary societies marked by the plurality of ever-clashing religious and secular visual regimes.

Bionote

Igor Jurekovič is currently an MA student of Sociology of Culture at the University of Ljubljana (Faculty of Arts), having completed his bachelor’s degree in English and Sociology. Taking part in the ERASMUS+ exchange programme, he studied at Utrecht University during the 2019/2020 academic year. He is currently finishing his master thesis on liberation theology and looking to enrol into a PhD programme in Ljubljana. His research interests lie within the perennial sociological topic of (political) economy and religion as well as sociology of science, currently focusing on contemporary workplace changes and their relationship with religious activities of the affected workers.

References

Baumgartner, Christoph. 2018. “Is There such a Thing as an ‘Offensive Picture’?” In Taking Offense. Religion, Art and Visual Culture in Plural Configurations, edited by Christiane Kruse, Birgit Meyer, Anne-Marie Korte, 317–339. Paderborn: Verlag Wilhelm Fink.

BBC, 2020. “Jägermeister logo does not offend Christians, Swiss court rules.” BBC, February 20, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020 (weblink).

Brown, Wemyss. 1910. “St. Hubert.” In Catholic Encyclopaedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. New Advent retrieved April 7, 2020 (weblink).

Frankfurt, Harry G. 2003. Necessity, Volition and Love. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jägermeister. 2020. “The Hubertus Legend – Story behind the Stag.” Jägermeister, retrieved April 8, 2020 (weblink).

Kruse, Christiane, Birgit Meyer, Anne-Marie Korte, eds. 2018. Taking Offense. Religion, Art and Visual Culture in Plural Configuration. Paderborn: Verlag Wilhelm Fink.

Kruse, Christiane. 2018. “Offending Picture. What Makes Images Powerful.” In Taking Offense. Religion, Art and Visual Culture in Plural Configurations, edited by Christiane Kruse, Birgit Meyer, Anne-Marie Korte, 17–58. Paderborn: Verlag Wilhelm Fink.

Swissinfo. 2020. “Jägermeister is not religiously offensive, court rules.” Swissinfo, retrieved April 8, 2020 (weblink).