Mariam Goshadze

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, in Christian Orthodox churches across Eastern Europe and several post-Soviet countries, the age-old altercation between religion and science is condensing around a small material object – the communion spoon. This shared utensil, used to deliver sacramental bread and wine to the parish, is now brandished by liberal secularists as the ultimate insignia of “backwardness” that the Orthodox clergy epitomizes.

Fig. 1: A Communion Spoon.

Riding out the period of self-isolation in my own country, Georgia, I have had the opportunity to closely observe the sleeping dogs of secularism waking as, in the course of the highly medicalized discourse precipitated by the pandemic, “blind faith” is targeted as the omen of mass-infection. Despite various restrictions imposed by the Georgian government, the Georgian Orthodox Church refused to replace the communion spoon with reusable plastic spoons. In the words of Giorgi Andriadze, member of the Fund of the Catholicos-Patriarch:

The communion is faith in Christ; if you take the Eucharist and become one with God, who would you become infected from? That would mean that there is no God. If you take communion in faith, if God comes to you, what virus could defeat you? Is the virus stronger than God?

While academic conversations are preoccupied with the ins and outs of the Constitution of Georgia, the nature of the country’s secularism, and the limitations that should or should not be imposed on the Church, I have been thinking about the oddly post-Protestant flavor of the criticisms waged by the liberal faction of society.

Before getting into the meat of the matter, let us briefly look at the star of the dissension – the sacramental spoon. The use of the spoon to serve consecrated bread immersed in a chalice filled with consecrated wine was established in Eastern Christianity from the eleventh century onwards, gradually replacing the former method of receiving the Holy Communion in the hand and then sipping wine directly from the chalice (Taft 1996). From a theological perspective, the eucharist is the cornerstone of Eastern Orthodoxy and inevitably, proper practice is crucial for its successful implementation. The scriptures suggest that as “the mystery of Christ” and “the mystery of the Church,” the communion ensures the worshipper’s most intimate union with God as promised by Christ at the last supper:

I am the living bread which came down from heaven. Whoever eats this bread will live forever. This bread is my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world. (John 6:51 NIV)

Very truly I tell you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you. Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise them up at the last day. For my flesh is real food and my blood is real drink. Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me, and I in them. (John 6:53-56 NIV)

Not unlike Catholicism, when an Orthodox Christian steps up to the altar, she is receiving the real flesh and blood of Christ rather than its symbol or representation. Based on this differentiation, in a universe that is faith-filled, the sacrament could not be held accountable for transmitting a virus, even if the germ theory of disease suggests otherwise. This is not to say that the idea of the divine presence in the eucharist is not contested within Christian circles. “One of the greatest sources of violence in Western history,” writes Robert Orsi, “has been the question of what Jesus meant when he told his apostles to eat his body and drink his blood and to do so always in remembrance of him” (Orsi 2016, 16). The controversy exacerbated with the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century. At the same time as the eucharist was subjected to impassioned theological debates, it also emerged as the key attribute of the Protestant claim on “modernity.” The Protestant emphasis on the mind’s ability to receive faith rendered bodily engagement with the sacred typical of both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches as pre-modern and grossly profane (Mellor and Shilling 1997). Instead, Protestants assimilated the Cartesian partition of body and mind, where the latter was assigned a superior status as the seat of rationality and hence, the foundation of “modernity.” Self-proclaimed as the “religion of modernity,” the Cartesian rift inherent in Protestantism also overlapped with the post-Enlightenment dissociation of the church from the state.

The ongoing debates regarding the communion spoon largely reflect this time-honored theological split between fleshly and spiritual forms of Christianity. In the post-Protestant era, much like Catholics, Eastern Christians manifested themselves as the people of embodied and literal presence. Notwithstanding this ontological standing, secular condemnation of ritualized religious practice often unknowingly incorporates the Protestant critique of embodied Christianity. Going back to the Georgian context, the secular criticism of the Church has revolved around the vilification of “fleshly” or “ritualized” devotion. “Christianity is not fetishism, it is not faith in a spoon, slaughtered sheep, or any other object where the physical form is favored over content and idea,” recently wrote a prominent Georgian public figure as he condemned the so-called “spoon-worshippers” for failing to see the true meaning behind Christianity. The underlying philosophy behind this position is that religion can only be tolerated in a secular context if it condones markers of progress – representation and ideas, and brushes aside physical expressions of the sacred. Indeed, a Georgian theologian recently expressed his concern with the fact that worshippers “are not interested in the conceptual attributes of Christianity, but rather its ritualistic and physical expressions.” In the eyes of the Georgian secular moderns, the belief that Christ’s flesh and blood could not transmit the virus is rendered not only as grossly “primitive” but also verging on “amoral.”

On the other side of the fence, the Patriarchate has been maintaining the immutability of the eucharistic practice. In an official statement made on February 29, the Holy Synod insisted that the flesh and blood of Christ cleanse and heal both physical and spiritual ailments, and under no circumstances could they have adverse effects. Then again, Orthodox Churches elsewhere have succumbed to the growing public pressure and introduced changes to the communion. The Ukrainaian Church, for instance, switched to the pre-spoon method of accepting communion in hand, and Russia, the world’s largest Orthodox congregation, ordered the spoons to be sanitized.

Offenses hurled at the devotees and clergy of the Georgian Orthodox Church – “magical,” “pre-logical,” “witless,” “fetishist,” give us a clear picture of what the secular moderns consider to be unacceptable forms of religious expression in a “civilized” society. The distinction ultimately comes down to two separate conceptions of religion – religion as a system of ideas and religion as practice, a differentiation that plagues not only religious studies as a discipline, but also all public discourse on acceptable forms of modern religiosity. Thus, unbeknownst to many, the image of an idea-based, spiritually oriented “normative modern religion,” is part and parcel of the Protestant critique of embodied Christianity, which in turn derived from theoretical debates over the eucharist. Advocates of “modern religion” proclaim the supremacy of the rational mind and condemn all forms of ritualism as attempts to manipulate the divine. In a theoretical framework where the eucharist is a symbol of a spiritual communion with the divine, a plastic spoon is as effective, or might I say ineffective, as a gold pleated shared spoon in doing its job.

Fig. 3. Screenshot of an article addressing the matter. Source: RadioFreeEurope.

In times of crises when humans are inclined to hunt for scapegoats to alleviate their all consuming fear for their lives, it could be useful to remember that hierarchical arrangement of the categories of magic, science, and religion along an evolutionary ladder is a post-Enlightenment project actively utilized to warrant the subordination of individual communities. Of course, this is not to say that criticisms waged against the Georgian Orthodox Church are unjustified. Article 8 of the Constitution recognizes “the outstanding role” of the Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia, a status that is both an outcome and a stimulus behind the gradual empowerment of the institution and its behind-the-scenes anchorage in political decision making. On the most basic level, the Church enjoys substantial state funding, tax exemptions, and other privileges. Beyond that, it wields an often unmediated influence on electoral results, and its individual representatives have been accused of corruption and sexual abuse, among other crimes. While I occasionally come across justified censure of the Church’s transgressions, most of the criticism waged by the secular liberalist faction of society is couched in the familiar “primitive” versus “civilized” binary where material and physical aspects of devotion are central to the argument. In this rendering, an average church-goer is at best viewed as a pleasant yet archaic vestige of the past that will slowly disappear as humans reach a higher level of evolution.

The ultimate question, then, is how to practically navigate the ontological fault line that separates religious and secular epistemologies in times of acute socio-economic crises. When the belief that the sacred eucharist cannot partake in the transmission of the virus clashes with the germ theory, which mandates that the virus can be spread via human saliva, how do we guarantee safety without undermining theological claims of various professions of faith?

In circumstances like this, monitoring and mediation of religious activities envisioned in a secular political setup can prove to be beneficial for the common good. Granted, tempering with the communion spoon would require complex institutional decision-making and theological modifications; even so, the state could order suspension of all church services and limit access to places of worship, especially in the course of Easter when church attendance is at its highest. There are already several precedents for government-imposed restrictions amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in the Eastern Orthodox realm – Serbia and Romania placed a ban on religious services, and the Holy Synod of the Greek Orthodox Church suspended all church activities and postponed the last Divine Liturgy of the Resurrection to May 26 so that worshippers can attend once restrictions are lifted. Regrettably, the Georgian government failed to demonstrate its competence in this regard. The country declared a state of emergency on March 21, and imposed additional restrictions on March 31 and April 17, gradually banning large gatherings and public or private transportation, closing down all nonessential businesses, restricting access to public cemeteries, and imposing a curfew for part of the day. Contrary to expectations, these restrictions have been repeatedly dodged by the Patriarchate by virtue of a constitutional exemption. Article 71 licenses the state to suspend various freedoms in the time of emergency, yet freedom of belief, religion, and consciousness is not affected. Nonetheless, Article 16.2 mandates that that the right to religion may be restricted “in accordance with law for ensuring public safety, or for protecting health or the rights of others, insofar as is necessary in a democratic society.” In other words, while the state of emergency does not apply to religious institutions, the government refrained from taking advantage of its right to restrict the freedom of religion for public safety, leaving it up to the worshippers to take precautions.

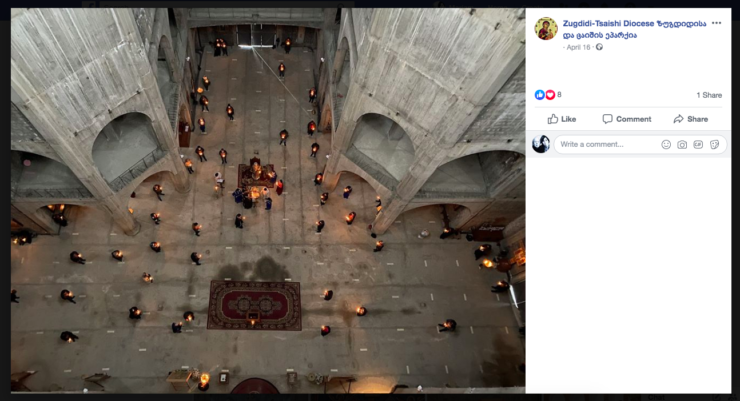

Fig. 4. Screenshot of Palm Sunday Service photo posted on the Zugdidi-Tsaishi Diocese Facebook page.

Despite the ongoing criticism and agitation, Georgia has not yet witnessed the highly anticipated “church-cluster” of infections. As we lie in wait for the ramifications of the Easter services, it could be comforting to remember that humans can easily switch between “mystical” and “practical empirical” frames of mind as they navigate sacred and secular spaces. Hence, an individual who accepts the eucharist from a shared spoon without hesitation could potentially also stand two meters away from other worshippers and follow the necessary guidelines in public spaces.

References

Ananidze, Jaba. 2020. “ეკლესია ჯიბრში ჩაუდგა პანდემიას (The Church is Obstinate in the Face of the Pandemic).” Netgazeti, March 18. Accessed April 14, 2020. Link.

Barberá, Marcen Gascón, and Milica Stojanovic. 2020. “Serbian, Romanian Priests Asks for Waiver to Hold Easter Masses.” BalkanInsight, April 13, 2020. Accessed April 16. Link

Bughadze, Lasha. 2020. “თვითმადიდებლობიდან კოვზმადიდებლობამდე (From Self-Worship to Spoon-Worship).” RadioFreeEurope, April 3. Accessed April 12, 2020. Link.

Kokkhinidis, Tasos. 2020. “Greece to Celebrate Easter Divine Liturgy at Midnight May 26.” Greek Reporter, April 3. Accessed April 12, 2020. Link.

Lomsadze, Giorgi. 2020. “Coronavirus Testing Georgia’s Faith in its Church.” Eurasianet, March 23. Accessed April 18, 2020. Link.

Mellor, Philipp A. and Christ Shilling. 1997. Re-forming the Body. Religion, Community and Modernity. London: Sage.

Orsi, Robert A. 2016. History and Presence. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Synowitz, Ron. 2020. “Coronavirus vs. the Church: Orthodox Traditionalists Stand Behind the Holy Spoon.” RadioFreeEurope, March 17. Accessed April 12, 2020. Link.

Taft, Robert F. 1996. “Byzantine Communion Spoons: A Review of the Evidence.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 50: 209-238.

“ასეთ პერიოდებში მორწმუნენი არ უშინდებოდნენ საერთო კოვზით ზიარებას, პირიქით — საპატრიარქო (In Times Like This, Believers Never Refrained from Taking the Holy Communion).” 2020. Publika, February 29. Accessed April 12, 2020. Link.

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.