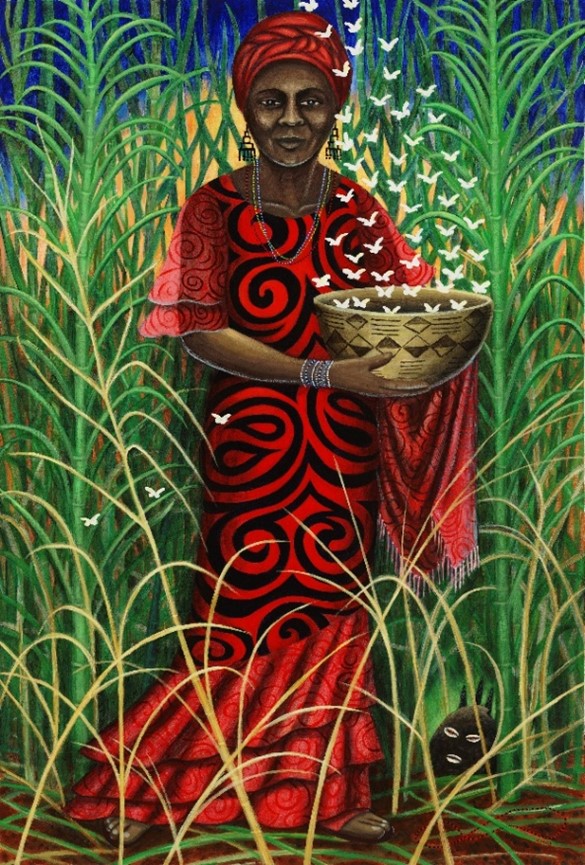

One of the enduring images we have from our fieldwork in Perico, Cuba is that of Hilda Zulueta (image 1). During our interviews with her about the religious tradition known as Arará, she sang Arará chants while dancing their accompanying movements and gestures. We sat on her porch often for 2 hours or more while she narrated amazing stories that imbue Arará history in her community, her face animated with memory. She took us to sacred sites featured in some of her stories and directed us to a sacred lagoon with another member of her community. When Hilda arrived at the ritual ceremony, attendees were relieved, for they knew that Hilda’s deity, known as Eleggua, was powerful. When Hilda danced, Eleggua would almost always arrive via possession and share prophecy with those in attendance.

The historical and religious knowledge Hilda shared illuminated connections between Cuba and West Africa. As a result of the transatlantic slave trade, the Ewe and Fon peoples from West Africa arrived in Cuba, where they were forced to work in the sugarcane fields. Their descendants found ways to keep their cultural traditions and ritual practices alive by revising liturgical forms and languages. The label Arará came to designate the resulting religious identity in Cuba. For over two decades, we engaged in research exploring shared attributes of artistic and religious traditions from each side of the Atlantic. Our research focused on two communities with Arará heritage in Cuba — Perico and Agramonte — and two Ewe communities in West Africa — Dzodze, Ghana, and Adjodogou, Togo.

During fieldwork, stories and oral history narratives emerged as critical, rich, and sensorial data. The veracity of the stories we encountered, such as those from Hilda, date back to stories from interlocutors’ parents, who heard or witnessed the stories from their parents, and so on. These stories were often told to us as we sat in sacred spaces, such as houses belonging to important elders that contained altars dedicated to powerful deities. Stories, particularly those shared with us in Cuba, tell of the legendary elders who arrived from Africa, enslaved, alongside their deities. Stories also tell of the critical reimagining of religiosity that enabled both deities and elders to survive under the weight of enslavement.

Hilda requested that we not be like another scholar who came for interviews, but never did anything with the information. Her request was a resounding echo that became the chorus of our project. And so we approached ethnography as artists. Dance, possession, or storytelling came to be seen as performances of social memory and cultural identity, manifested through dance, songs, and material representations recognized by the community as sacred. The religious intersected with the aesthetic — further entangling the divine with the sublime — in ways that demanded both art and scholarship. Beginning as an art installation titled Secrets Under the Skin (image 2), the project now takes the form of text. We detail this approach in the new book, Situated Narratives and Sacred Dance: Performing the Entangled Histories of Cuba and West Africa (for more information, see the announcement below this text).

for Latino Arts, San Francisco. Photo by Brian Jeffery

The turn to text presented many challenges. How does one write what Mattijs van de Port (2011) calls an “ecstatic encounter” — the sensorial, embodied experience of religious expression — using the rigid structure of academic language? How might we conform to the expectations of an academic audience while continuing to honor the discursive qualities of religious performativity in Arará communities? How might writing be both a method of transcribing and also one of live performance?

For us, in order to convey not just the content of religious attributes but also the performance through which those attributes come alive, we relied on literary styles of writing. Techniques like characterization, dialogue, setting, and figurative language give a sense of what it means to dance at a ceremony or witness ritual possession. Our chapters document stories and oral histories rarely shared outside their respective communities in ways that evoke the sensorial experience of being in the moment.

The first part of the book draws from performance theory to provide a framework for approaching fieldwork using true fiction and choreographed narrative. True fiction builds from James Clifford’s classic argument for the literary turn in ethnography (Clifford and Marcus 1986). Layers of interpretation unfold during ethnographic encounters, creating the conditions of fiction. The designation of “true” signifies the obligation to honor the stories as they were told to us.

Choreographed narrative provides a method for arranging the stories in ways that illuminate meaning while remaining closer to fact. This framework defines writing as a method of inquiry into meaning and truth, which are not always the same as facts. What something is differs greatly from what something means. Even in the most scientific genres, writing requires an arrangement of lived or imagined experience—a narrative—to generate meaning (Ricoeur 1995).

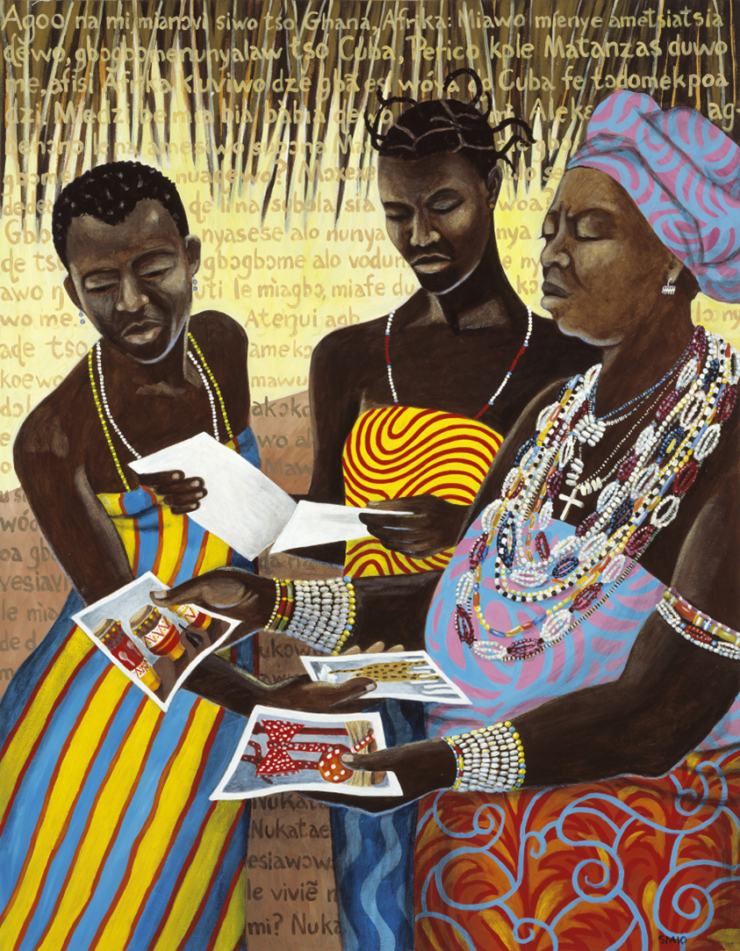

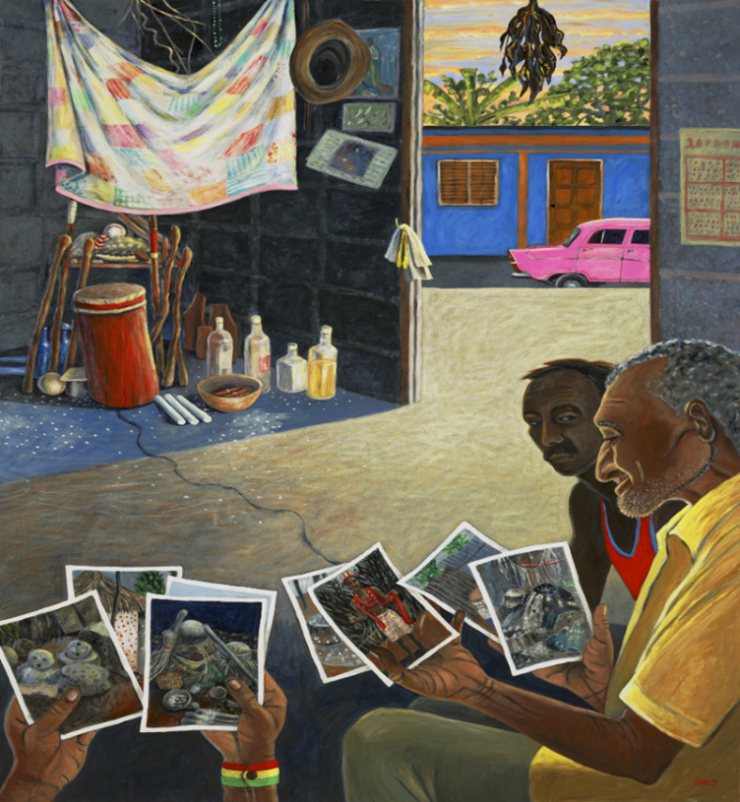

The rest of part 1 shares the stories about Arará’s history across Cuba and West Africa. These stories, like the other forms of art created by our collaborative team, opened up opportunities for creative interaction between Cuban and West African communities. We carried many photographs, videos, and questions back and forth across the Atlantic, facilitating a dialogue of ecstatic encounters (image 3).

While sharing these artifacts, religious practitioners were asked what they noticed about potential shared attributes of religious forms, dance steps, and drum rhythms. Cuban elders and religious practitioners sent questions for Flanders Crosby to ask of the Ghanaian and Togolese practitioners. Flanders Crosby would film those sessions, have them translated, and then carry those conversations back over to Cuba for further reflection (image 4). This process served as the critical method for cross-cultural knowledge generation across the fieldsites.

Part 2 unpacks the process of creating the Secrets Under the Skin contemporary art installation that was our first rendition of our fieldwork data. The contributions made by artists Susan Matthews, Brian Jeffery, Marianne M. Kim, and Melba Núñez Isalbe provide an in-depth look at the collaborative process upon which this book, and the installation before it, so depended. In total, part 2 details the intersecting voices that together formed our approach to ethnographic work using methods from various art media. In an attempt to honor the often-iterative form of oral storytelling (and refute the idea that text is inherently linear), part 2 both provides the foreground for the book as well as a post-book reflection of how the translation of our fieldwork into text extends the project’s overall aims, which began with art installations.

The dialogue and engagement fostered between communities (not just the fieldsites but also viewers of our art and readers of our book) would not be possible without blurring the boundaries of text. The printed word has been both the most dominant and the most exclusionary representation of knowledge in that it requires training in certain forms of literacy in order to access the knowledge. Alongside text, we hope to offer other forms of access by making explicit use of art. Through dance, video, photography, and text, we aim to increase the dialogue and engagement with – the metaculture of – Arará religious identity. The more diverse our forms, the more who can access the conversation, the more we have satisfied Hilda’s request.

Bionotes

Jill Flanders Crosby is a professor in the Department of Theatre and Dance, University of Alaska Anchorage. She began research in Ghana in 1991, and focused on ritual dance forms in Ghana, Togo and Cuba from 1997-2018. She spearheaded a collaborative art installation inspired by her extensive Ghanaian and Cuban fieldwork. She is currently conducting oral history research in the Cook Islands of the South Pacific among dancers, choreographers, and composers.

JT Torres is an assistant teaching professor of English at Quinnipiac University. Alongside Jill Flanders Crosby, he co-authored Situated Narratives and Sacred Dance, which explores the performance of identity in the ritual ceremonies of Arará communities in Cuba. He is also the author of Taking Flight, a fictional story of a young boy’s relationship with his Cuban refugee grandmother. His work brings together art and qualitative methodologies to understand the ways humans read and write their relationships within more-than-human entanglements.

Situated Narratives and Sacred Dance: Performing the Entangled Histories of Cuba and West Africa is published in hardcover format by the University Press of Florida. Through an etnographic approach that foregrounds storytelling and performance as alternative means of knowledge, the book explores shared ritual traditions between the Anlo-Ewe people of West Africa and their descendants, the Arará of Cuba, who were brought to the island in the transatlantic slave trade.The authors draw on two decades of research in four communities: Dzodze, Ghana; Adjodogou, Togo; and Perico and Agramonte, Cuba.

References

Clifford, James, and George E. Marcus, eds. Writing culture: the poetics and politics of ethnography. Univ of California Press, 1986.

Ricoeur, Paul. Figuring the sacred: Religion, narrative, and imagination. Fortress Press, 1995.

Van de Port, Mattijs. Ecstatic encounters: Bahian candomblé and the quest for the really real. Amsterdam University Press, 2011.