Veerle Dijkstra

In the period of heightened insecurity the COVID-19 pandemic has created, the need for community and spiritual solace is high. Yet, for religious people the current ‘five feet society’ (anderhalve-metersamenleving) makes satisfying this need through conventional means impossible. Religious communities in the Netherlands cannot congregate with more than 30 people and are strongly advised against congregating at all. Religious worship, already considered a largely private affair in the Netherlands, has been confined to the privacy of people’s individual homes even further. As with any disruption of life, however, the Corona crisis also provides impetus for creativity and opportunities for reimagining societal conventions, including those pertaining to religion. Having been forced to go private, religious communities everywhere have directed their attention to ways of continuing practicing their faith in community. Many find these solutions online.

It is interesting to observe and investigate how COVID-19 influences the way religious communities negotiate their attitude towards digital media. Below I share some preliminary observations from following the news and virtually attending Christian worship services in the Netherlands in the period of Easter. These observations indicate the widely diverging approaches that Christian organizations take regarding their ‘online presence’ and give rise to a host of questions relating to changing practices of worship in the Netherlands, authenticity, and community-building. With this entry I aim to continue the discussion on the relationship between religion and modern mass media (see e.g. Meyer 2009; Meyer and Moors 2005) with a specific focus on social media, and hopefully stimulate ideas for future research.

Within the Dutch Christian community livestreaming via the internet is a widespread method used for worship at the time of COVID-19. Dutch Christian newspaper Nederlands Dagblad reports that the number of visitors of online church services has multiplied by four. Furthermore, Kerkdienstgemist, a popular streaming service, mentions that the evening of Good Friday was the busiest moment ever recorded in the history of the organization. In addition to the rise in visitors, the number of Dutch church services offered also appears to have increased considerably. Within the religious content offered online, via Kerkdienstgemist, but also via Facebook, YouTube, Kerkomroep and other services, great variety exists. This variety can roughly be organized on a spectrum ranging between restriction and embrace of digital technology and its affordances. The position of online content on this spectrum is explained in part by practical matters concerning time, money and available technological skills on the part of religious organizations. Yet, it can also function as an indicator of religious communities’ varying considerations about the proper or desirable use of digital media.

Many churches seem to approach online audio(visual) material and livestreams as relatively neutral enablers necessary to bridge the distance between people at home and a service taking place in a church. Usually, these churches maintain an ordinary liturgy and the service in the first place addresses their familiar congregations. Videos tend to be shot from the back of the church, zooming in on the altar. In some cases multiple camera angles are used, or texts and separate videoclips are edited into prerecorded videos. Furthermore, services often remain available online after the original church service has ended so people can watch or listen at a chosen time. In these ways churches make moderate use of the unique possibilities digital media affords. In general, however, digital material often appears to be intended to recreate an already familiar church experience, not one enriched in unexpected digitized ways.

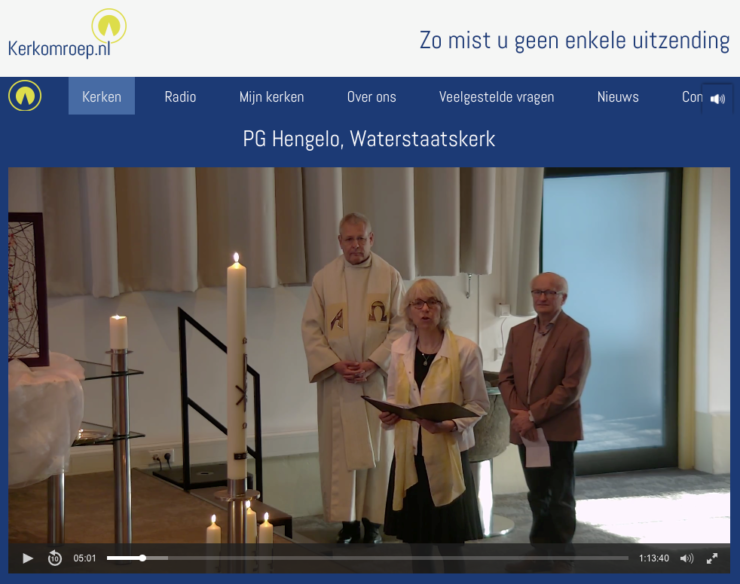

Some churches aim to mimic an ordinary church service not only via audiovisual material, but also by inviting people at home to actively participate in certain rituals and behaviors. In its Easter morning service the Waterstaatskerk in Hengelo (PKN), for instance, does this. After carrying in the Easter candle and lighting three additional candles, a woman directly points her gaze towards the camera and invites people at home to also light a candle and celebrate together.

Screenshot (April 4, 2020) of the Easter morning service by the Waterstaatskerk in Hengelo, streamed on Kerkomroep. Visitors at home are invited to light a candle.

Many churches in the Netherlands offered online material of church services already before the onset of the anti-COVID-19 measures. After the measures started, some, such as the Hervormde Kerk in Bodegraven (PKN), invested in their online material, supplementing what used to be only audio with video. This indicates that this church sees value in accentuating the visual dimension of a church service. There are also churches, such as the Hersteld Hervormde Kerk in Staphorst (Restored Reformed), that continue to only offer audio material. This choice could be argued to be in line with a Protestant theology that privileges the Word. Yet, the general popularity of (online) listening to church services also indicates the likelihood that this approach is the result of practical rather than theological considerations.

One also finds restrictions to digital mediation that betray a more overt theological foundation. In a decree written on the 25th of March of this year, the Catholic Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments advises Catholic bishops to use “telematic broadcasts” to connect to the faithful. Interestingly, it clearly states that these broadcasts should be “live (not recorded)”. This indicates that for this Catholic body a live connection between a church and its audience is considered necessary in order to mediate the presence of God – as well as, perhaps, to protect the sacraments. Indeed, in the context of religion, online presence encompasses not only the presence of a church and its clergy but also that of the divine. This implies certain (conscious) restrictions to the possibility of online mediation of divine presence. Yet, as is noted also by Johanneke Kroesbergen-Kamps (see also De Witte 2008), a church service without a live congregation may also be found to be incomplete, especially for Christians with a charismatic orientation. In this case it is through the horizontal interaction between a pastor and (members of) a congregation that a vertical interaction with the divine is enabled. Prerecording a church service for people to individually watch at a chosen time would detract from this interactional dimension and thereby, arguably, from experiencing the divine. From this perspective it seems reasonable that an affordance of digital media, endless reproduction, would be restricted in order to safeguard the presence of God.

All online Catholic services from the Netherlands I encountered were broadcast live. Yet, contrary to my expectation I also noted that services are not necessarily removed from the Internet after the live service has taken place. It would be interesting to know whether this decision by Catholic churches to keep past services available online is the result of theological or other considerations. Furthermore, this observation invites an investigation into the possible discrepancies between worship as it was envisioned by one layer of church leadership, how it is enabled by another, and practiced by ordinary worshippers at home.

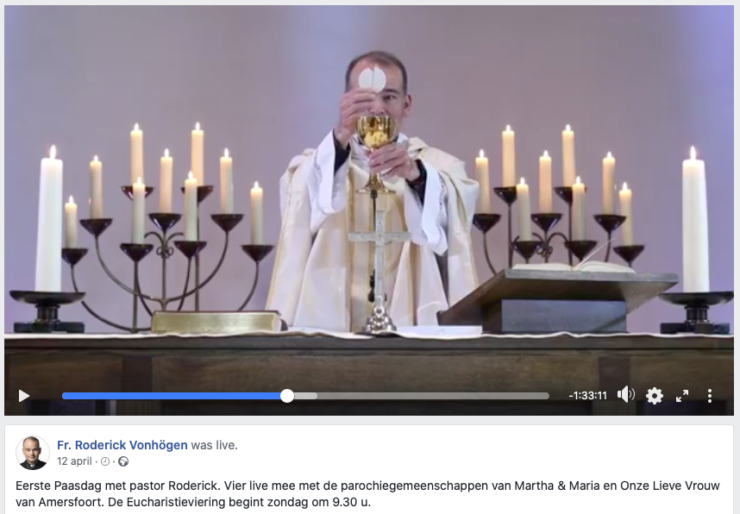

The limits to digital mediation of religion also become clear in relation to physical rituals such as the Eucharist. People cannot physically receive the Eucharist in church. Certain Protestant churches find a solution to this problem by inviting worshippers to have their own bread and wine at home. For Catholics, for whom God is present in the Eucharist, this is not a suitable alternative. By lack of the physical Eucharist the Katholieke Bijbelstichting (Catholic Bible Foundation) and various Catholic churches suggest people to have a so-called ‘spiritual Communion’ as a substitute. This spiritual Eucharist, Catholic bishop Michel Hagen explains for Katholiek Nieuwsblad, is supposedly able to act as a substitute for the physical Eucharist in terms of creating proximity to Jesus Christ. However, in terms of community building it remains an inferior alternative.

Screenshot (May 4, 2020) of the celebration of the Eucharist on Easter morning by the Catholic Onze Lieve Vrouw van Amersfoort Church in Amersfoort. People at home are expected to engage in the spiritual Communion. Streamed on Facebook.

Some churches thus encounter the limits to online mediation of religion or restrict their online presence. On the other end of the spectrum are online worship services organized by communities that embrace digital media as instruments that can enable a renewed way of experiencing religion with new possibilities. Some organizations, such as Presence, quickly emerged with online forms of worship on YouTube when the anti-COVID-19 measures were introduced. Other communities, such as the Evangelical church GODcentre in Gouda, had developed a strong online presence long before the COVID-19 crisis and were well-prepared for a forced change in worship style.

A key affordance of digital media is their accessibility. When no passwords are used, anyone with access to the Internet can visit an online church service. When this accessibility is combined with online content having a large appeal, through pre-existing status of the organizing body, high production value, or successful promotion, communities are able to organize worship on a large scale and engage an audience comprising members of various churches as well as a new demographic. Often these forms of worship have a high production value and blur the lines between religion and entertainment. An example is an initiative started by GODCenter. This initiative, ‘Samen kerk Samen sterk’, called for a nation-wide online celebration of the Eucharist. In contrast to the spiritual Communion suggested by Catholic churches, this national Eucharist invited people to partake in the ritual consumption of bread and wine from home: “[a]re you making sure you are prepared to celebrate [the Eucharist] with us?! Otherwise still get some Matzen/bread & wine tomorrow ? [emoticon of hands raised in the air]”. Initiatives like these, as well as an event such as The Passion, which was organized online this year, allow large numbers of people to practice their religion in ways impossible without the internet (see also Van den Hemel).

Screenshot (April 22, 2020) of the celebration of the Eucharist on Good Friday by Samen kerk Samen sterk. Streamed on YouTube, following a service by Presence.

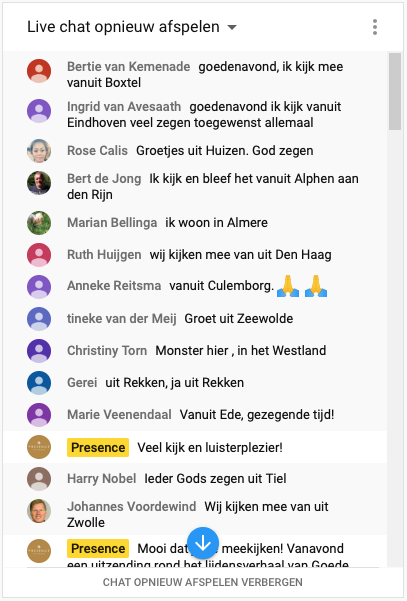

Visitors of these livestreams also recognize their capacity to create communities undefined by geographical boundaries. After one visitor shared the message “Good evening, I am watching from Boxtel” in the live comment section during a Good Friday service by Presence, other commenters voluntarily shared their locations as well. This resulted in a list of locations ranging from The Hague to Eindhoven, to even Yogyakarta. In the words of one visitor: “where we are one with Jesus church walls disappear”.

Screenshot (April 22, 2020) of the comment section during the Good Friday service by Presence. Streamed on YouTube.

As the Corona crisis continues it is interesting to follow how modes of worship develop. Will online engagement with religion obtain a more permanent position as an authentic form of worship in the future? It remains to be seen whether churches are able to continue to engage their congregations in online worship in the long run. Are spiritual Communions, live chat boxes and virtual coffee hours able to compete with unmediated interpersonal interaction? Alternatively, which churches or communities will not only maintain but increase their number of followers? Forms of worship and patterns of affiliation are bound to transform as a result of COVID-19. Here I have primarily aimed to provide some first ideas about types of online content currently offered by Christian organizations in the Netherlands. In addition, it would be interesting to explore how individual people give shape to their worship from home. Do they follow worship as it was intended by church leadership? Is the ‘do-it-yourself’ form of worship—deciding yourself where to sit, whether to sing, or whether or not to wear your ‘Sunday best’—better adapted to people’s individual needs? Will online religion be able to accommodate the individualizing trend in religious engagement while maintaining the security of an imagined community?

For now, raising questions is simpler than answering them. For the period to come I look forward to discussions and research projects that will further our insight into the way religion responds to and is affected by the unusual circumstances that the COVID-19 pandemic creates.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Birgit Meyer and my peers Mariska de Boer and Mariia Wäre for reading and thinking with me on earlier versions of this text.

Bio

Veerle Dijkstra is a first-year student in the Research Master in Religious Studies at Utrecht University. For now, her main interests are the materiality and corporeality of lived religion and religious belonging in relation to hybrid religiosities. She is currently working towards a research plan for her master’s thesis, which will concern the relationship between religion and modern mass media and the way the COVID-19 pandemic affects worship in the Netherlands.

Veerle obtained her bachelor’s degree summa cum laude from University College Utrecht, with a double major in religious studies and anthropology.

References

De Witte, Marleen. 2008. “Spirit media: charismatics, traditionalists and mediation practices in Ghana.” PhD diss., University of Amsterdam.

Meyer, Birgit, ed. 2009. Aesthetic Formations: Media, Religion, and the Senses. New York (NY): Palgrave Macmillan.

Meyer, Birgit, and Annelies Moors, eds. 2005. Religion, Media, and the Public Sphere. Bloomington (IN): Indiana University Press.

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.