Visiting the Religious Matters-project in March 2019, I was struck by the cultural plurality in the streets of Utrecht. In a university city this is not at all unusual. But Utrecht has more international relations than Marburg, where I come from. This pluralism is rooted in the Netherland’s history and has many facets: from colonialism up to contemporary migration and globalization. The scholarly debate therefore goes far beyond easy concepts of integration and critically observes structural ascriptions to certain groups that might be normative for individuals (see Meyer 2018: link).

I quickly had to ask myself about the dynamics of this plurality. During my stay the shooting incident in a tram took place (on 18 March) and immediately the city administration declared the highest threat level, and I deemed Utrecht to be prepared for such an emergency. This went along with the, for me unusual, entrance control at train-stations or mounted police on patrol in the city centre. Utrecht’s population faces tensions, which became even more obvious at the elections two days later. Reflecting about “religious matters in an entangled world” and researching buildings and material culture, which are my topics as well, might be another way to deal with plurality as scholars of religion. I would therefore like to share some impressions of mosques in the Netherlands.

The Ulu Camii mosque in Utrecht (inaugurated in 2015) is known for the aim to bridge different parts of society. It is placed in a highly visible location: passing main streets to the train station one can see the building with Ottoman Sinan-style elements in a modern design. In the light of my familiarity with German conflicts about the erection of mosque and negotiations about the places and architectural styles, I think that there must have been overall fruitful mechanisms of mediation around this building, otherwise it would not exist in its actual form.

Unexpected from the outside, it hosts a prayer room for Non-Muslims, called silence room. And on the ground floor on the same building, a highly visible restaurant is situated, as part of the Kebap Factory-chain. For those who take a separation between a “religious” and a “secular” sphere for granted, this might be a surprise. But in Islamic history restaurants or shops in a complex of a religious building are quite common. To rent parts of the property is part of waqf, the Islamic foundation, in order to fund a foundation for a longer time. To rent the place to a stylish transregional fast-food chain signals a self-confident presence of Islam in the Netherlands. Of course, this restaurant serves halal-products, but will also be visited by anyone who likes Turkish food.

Entering the mosque on a Friday afternoon, I was sent to the women’s department on a transparent and light balcony over the main prayer room. There I came to talk with some ladies with backgrounds in different parts of the world: Africa, Asia, the Near East and the Netherlands. Their lingua franca was Dutch. They switched to English to talk to me about their pride to have this mosque in their town. Here they find a place to loosely gather in their own public, to chat or to read in the Qur’an or – when younger, to record the call of the mucazzin with their smartphones.

From a scholarly perspective this building is an interesting example of spatial arrangements as part of negotiations between different parts of society. The final arrangement mirrors groups’ interests and their plural perspectives on one place (see Kim Knott, The Location of Religion 2005: link). It establishes boundaries, but at the same time bridges and offers possibilities for transitions (see Knott: Walls and other Unremarkable Boundaries 2015: link)The place and outward appearance of the building had to be defined in the community and also within a broader public (Verkaaik, Tamimi Arab, Beekers 2017: link). In German Muslim communities during the period of construction, intensive discussions concerning the functions and appearance of a building take place: between generations with different aesthetical preferences and between men and women (Beinhauer-Köhler/Leggewie, Moscheen in Deutschland 2009: link).

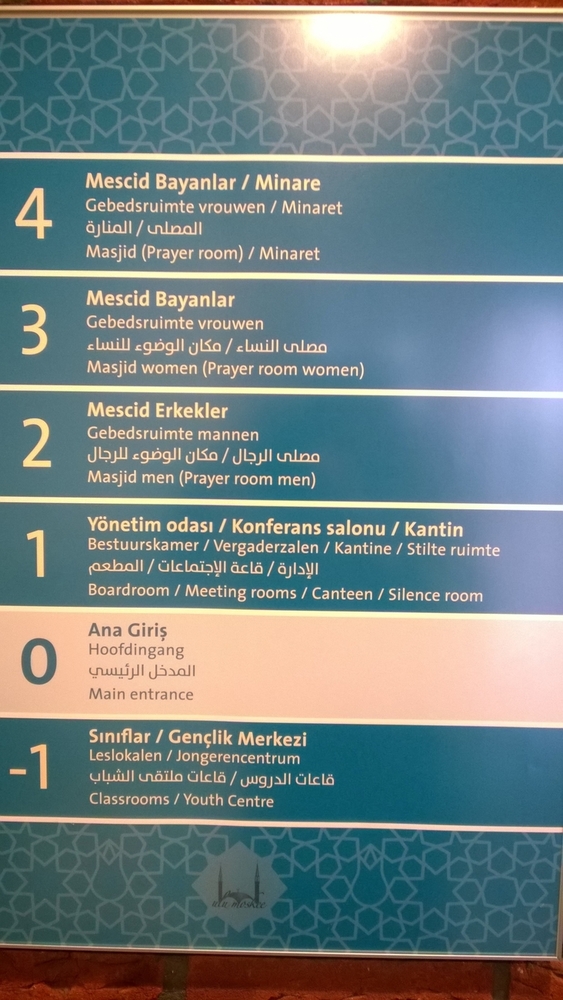

The location plan in the entrance hall still reveals such dynamics: Its four languages indicate a variety of visitors, from Turkey to the Netherlands, to the English-speaking world up to groups or persons with Arabic as their mother-tongue. This plan represents the founder’s and architect’s logic of the building’s inner arrangement in each floor: It ranges from an interest for education and care for the younger generation, placed in the basement, to the need for administering such a complex in the first floor. The “room of silence” for the non-Muslim public is also located here, close to the offices. This reflects a concept which does not follow the idea of a symmetric “interreligious dialogue”, which is hardly to be realized anyway, but it reminds of concepts of hospitality towards other religions, that German churches like to refer to. Interestingly enough, this room is indicated on the location plan only in western languages, which might guide visitors to certain parts and addresses those reading the information in Turkish or Arab as Muslims and suggest that they go to the main prayer areas. Moreover, this floor hosts a canteen, turk. kantin or arab. matcam (“restaurant”). This is of another type of space for consuming food than the public restaurant which has to be entered from outside. This canteen is a place for social gatherings of the inner community. Next comes the men’s – and main – prayer room with the prayer niche (mihrab) and the qibla-wall facing Mecca as well as the minbar for the sermon, all at the level of the huge rectangular semi-transparent window front.

Nowadays Islamic communities in many parts of the world discuss how to manage a separation of gender in such buildings. The solution here is somehow classical but with a modern twist that makes the women’s space attractive: The second floor is reserved for men, who enter the mosque traditionally in a lager number and might get access even via the stairs. The third and main floor for women is above. Even if sitting on a balcony, they are present in the main hall as well, as it is open towards the dome. Moreover, they have the privilege to get access to the top of the building in the fourth floor.

The plain staircase and elevator might be identified as a “third space” (Bhabha, Location of Culture 1993: link): Here the different groups easily meet for orientation and have a short exchange about their actual interest in a certain space. It is a “transfer area” and as such a place of its own, not to be confounded with Marc Augés concept of “non-places” (Augé, Non-Lieux 1992, transl.: Non-Places. Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity 1995: pdf). And also the rooms with a declared function are not as exclusive as the signs might suggest, as their visitors’ identities are multifaceted: I was not identified as a non-Muslim and not sent to the silence room, but got help, because of gender, to find the women’s prayer room. Situations enable transfers of spatial and social boundaries.

The solid appearance of architecture might also easily be misleading and yield the impression of a fixed use. The opposite is the case: People use even religious spaces and their material objects differently according to constantly changing interests (Jones, Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture 2000; Morgan, The Sacred Gaze 2005: article link). In this sense any place is somewhere “in-between”, as spatial constructions are in an elementary way formed by peoples’ movements – as Uwe Wirth argues (Wirth, Zwischenräumliche Bewegungspraktiken 2012: link). Visiting the Fatih Mosque in Amsterdam (described by Beekers and Tamimi Arab, 2016: link) one day later, a large travel group of girls from a Muslim boarding school in Belgium “captured” the main hall. They did not hesitate to pose for photographs in front of the prayer niche, the mucazzins microphone and the minbar. Only when the afternoon prayer started they were guided to the women’s department, in this case quite unattractive and narrow (and located in what was the altar space when the building still was a Catholic church), where they did what any class on tour would do: chatting, eating and playing with their mobile phones. The sheer material appearance and arrangement of a building should not lead to easy assumptions about fixed social boundaries inside. They are part of ongoing negotiations between generations in an entangled set of related cultures. Therefore, mosques are intriguing “public spaces”, which can easily be observed and tell us a lot about ways of being Muslim in the Netherlands.

Bärbel Beinhauer-Köhler

Bärbel Beinhauer-Köhler is professor for the History of Religions at Philipps-University Marburg, with a focus on Islam and plural spaces. From 14 – 23 March she paid a work visit to the Religious Matters programme. Her Publications include:

Bärbel Beinhauer-Köhler, Claus Leggewie, Moscheen in Deutschland. Religiöse Heimat und gesellschaftliche Herausforderung, München 2009.

Bärbel Beinhauer-Köhler, Spielräume religiöser Pluralität. Cairo im 12. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart 1018.

Her current research deals with material arrangements and social dynamics in museums: link

Photo: Bärbel Beinhauer-Köhler