Re-presenting the stuff of dreams and invisible forces, films feed the popular imagination

“It’s true, it’s true. All these things happen, all these things happen in real life”, Paulina, a fan of Ghanaian movies, told me at the beginning of my research on Ghana’s emergent local film industry in the fall of 1996. I was struck by depictions of the hidden operations of occult powers that also were at the center of testimonies and sermons in the phenomenally popular Pentecostal churches. Paulina’s point that Ghanaian films offer realistic representations of the unseen was made over and over again. Held to portray “things that happen,” film was taken as a device able to show what was conceived as “real” in its totality, encompassing the visible and the invisible. Of course, people knew that the invisible could only be depicted through special effects, but nonetheless many were inclined to see these depictions as truthful revelations. While these movies feature scary images of creepy beings that populate the most terrible nightmares, they also offer iconic images of a modern world that audiences long for, but which has not yet fully materialized for them. Trading in the stuff of dreams, films mirror and feed the popular imagination.

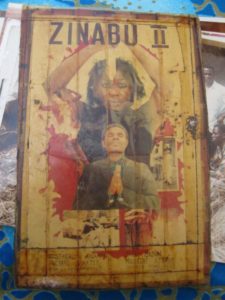

Poster for Zinabu II. Birgit Meyer

In her book, Copper Town: Changing Africa (1962) Hortense Powdermaker analyzes processes of social change in the Copperbelt, where she conducted research in a mining town (Luanshya) between 1953 and 1954. Interested in leisure activities as a prime site for African engagements with the Western world, she studied how people view movies. “Going to the Movies” (chapter 6) offers a fascinating description of how African spectators watch and comment on newsreels as well as cartoons, comedy and feature films. In the light of my own research on film in Ghana, I would like to highlight two points. The first concerns the preparedness of the audiences to embrace movies as offering a view into a new, modern world. Cowboy movies, she reports, were particularly popular as the hard-fighting cowboy—underdog and hero—was a figure African spectators, just as low class Americans in the United States, could easily identify with. “If I went to America, I would very much want to be a cowboy,” one man told her. But the appreciation was not wholesale and without critique. While boxing was appreciated, the use of guns was not: “I think America is a lawless country, if they can shoot people like that.” Powdermaker notes perceptively that the image of the cowboy was “an attractive hero for a people intensely fearful of losing some of their wide-open spaces to Europeans, who until recently held all the power.” Second, Powdermaker points out that people kept on wondering about the status of the moving images on screen. “The questions ‘What was real?’ ‘What was cheating?’ were a problem for many, educated and uneducated.” While “for many of us movies are a pleasant and easy form of escape,” this is different for Africans (“and other inexperienced audiences”) who do not have a true understanding of the medium of film. This can only be remedied, Powdermaker concludes, by more education about the nature of mass media and actual direct communication between Africans and Europeans in the Copperbelt. But she also states that “the problem of reality in the mass media is complex, not only in Africa, but everywhere.”

What I appreciate most in Powdermaker’s analysis, which offers one of the first accounts of cinema in Africa (see also Morton-Williams 1953, on northern Nigeria), is that she does not fall into the trap of presenting a fantasy of primitivism and assume that African audiences would simply take the images on screen for “real.” She introduces her interlocutors as critical viewers who do not take moving images at face value, but approach them critically based on their own experience and knowledge. The question of how film relates to reality has been debated in cinema studies from Kracauer to Cavell and Deleuze, and beyond. It is widely agreed that film does not simply represent a reality placed in front of the eye of the camera and cut and reassembled on the editing desk, but is real in its own right and intersects with reality at large. A focus on film is highly productive for understanding dynamics of world-making in specific situations, and allows us to grasp epistemologies rooted within a nexus of media, reality, and representation. So anthropological research on film is not simply about the use of film as a particular mass medium for communication, but unpacks the role of film in shaping common sensations and shared imaginaries of and in the world. Imaginaries do not only represent a world, they take part in making it. Synchronizing how audiences sense and imagine, films underpin a sense of being and hence of what is real.

Grounded in ethnographic research on the emergence and development of the Ghanaian video film industry between the early 1990s and 2010, my recent book Sensational Movies: Video, Vision and Christianity in Ghana (2015) focuses on low budget feature films (or video-movies) made in Ghana from the mid-1980s until around 2010. A similar video film industry arose in Nigeria and other countries across Africa (see, for example, Haynes 2016, Larkin 2008, and Krings & Okome 2013). In Ghana, the concomitant opening of the country to neo-liberal capitalism, the phenomenal rise of Pentecostalism and the deregulation of mass media in the mid-1990s facilitated the development of a new public sphere in which Christian viewpoints gained prominence and the previous state driven politics and aesthetics of representing culture were challenged. Different imaginaries clash with each other. In this context, new cultural entrepreneurs came to the fore who produced movies that resonated closely with ideas and experiences on the ground. They brought into view an urban imaginary of “a city yet to come” (Simone 2004), the contours of which are already apparent in the mess of the city: chic hotels, broad roads, fanciful restaurants, fenced mansions, haute couture. While the audiences studied by Powdermaker in the 1950s still took pleasure in witnessing images of a foreign and far away world, several decades later Ghanaian audiences enjoy the enveloping of their local circumstances into a desired frame that epitomizes global modernity. At stake here is not the appropriation of the foreign figure of the cowboy as a new hero in changing times, but the transposition of the familiar into iconic imagery derived from Latin American telenovelas and Hollywood that stands for the good life, progress, and success. However, this positive portrayal of urbanity also has a dark side: many movies also disclose how evil forces operate behind the facades of high modernity, engendering crime, betrayal, and death. The city depicted in movies entails both a dream of a better life and the specter of moral downfall and corruption.

Movie posters, Accra. Birgit Meyer

Grounded in Christian viewpoints and narratives, many movies make visible the unseen. This, Pentecostal preachers emphasize day in, day out is the realm of the “spiritual,” which is held to be populated by demonic and divine forces that shape what happens in the “physical” realm. The category of demonic forces also includes indigenous gods and spirits, diabolized since Christianity was first preached in the early 19th century. Film is featured as a medium for revealing the operation of the powers of darkness that afflict people and hinder health and well-being, yet are ultimately destroyed by the Holy Spirit. Thriving on the dualism of God and Satan, many movies depict how occult forces—such as witches, ghosts, mermaids, dwarfs, indigenous gods—cause the troubles and mishaps endured by the sympathetic protagonists. They invite a voyeuristic engagement with the occult forces Christians are advised to stay aloof from.

Critics charge these movies with misrepresenting Africa. This critique betrays a view of film as a truthful representation (in the sense of mirroring) of reality. However, this is not how film producers and their audiences understand the medium of film. In his sketch of African conceptions of “figurative representation” Achille Mbembe explains

that having the power to represent reality (to make images, carve masks, and so on) implied that one has recourse to the sort of magic and doublesight, imagination, and even fabrication, that consisted in clothing the signs with appearances of that thing for which they were a metaphor (2001).

It is not the mirror-like representation of a world out there, but a re-presentation in the sense of projecting a double. Not unlike carvers and priests, filmmakers also have the power and means to represent the world of everyday lived experience, understood as encompassing the physical and the spiritual, to movie audiences. Referring to a domain of partly hidden and secret forces and practices, figurations of the occult are special mediations of the invisible. They are phantasms, that is, impossible re-presentations that thrive in the vertiginous limbo of the visible and the invisible, the audible and inaudible, pinned down as pictures and yet elusive.

At work here is an African politico-aesthetic practice of figuration that is not primarily intended to represent or illustrate an outside reality, but instead to intervene in that reality by doubling it, as Mbembe suggests in his recent book Kritik der schwarzen Vernunft (Critique of Black Reason 2014). This double is not a direct mirror image, but a site for a ludic display of transgressions of all sorts which nourishes “the hope for an exit from the world as it was and is,” so as to “enable a rebirth of life and a continuation of the feast” (my translation). Important here is Mbembe’s understanding of African aesthetic practice as performative and curative, in that it deconstructs the world as it is and offers a glimpse of another future. Ghanaian video-movies are situated in this African tradition of figuration that does not aim to represent the world by mirroring it as accurately as possible, but rather to conjure the invisible and unleash creative energies to intervene in the world via a logic of doubling that involves transgression, revelation, and deception. Movies represent in the sense of figuring and figuring out: vision in action. In turn, the images that trace the causes of affliction may be experienced as potentially dangerous and even afflicting themselves, penetrating the imaginations of their spectators, haunting their dreams and daydreams.

Pondering the relation between film and reality, the question is not simply how or to what extent a film mirrors reality or is an illusion or dream, but more importantly “what happens to reality when it is projected and screened?” (Cavell 1971). Ghanaian audiences, just like Powdermaker’s interlocutors, are inclined to dismiss certain cinematic images as illusionary or artificial. But this is not an assessment in the light of an objective reality out there that is judged to be represented truthfully or not, but one grounded in a particular take on the real. Film is a vital node in the deployment and sharing of imaginaries that make things real. This insight is not limited to Ghanaian video-movies alone, but aids our understandings of the role of film in the politics and aesthetics of world-making everywhere.

Dream factories

Birgit Meyer

March 9, 2017

This article appeared on the Anthropology news site: Link