Tuhina Ganguly

The “stay fit” mantra seems to have found renewed salience in the present pandemic context in India and globally as privileged people find themselves at home, stranded away from gyms and parks. The call to nurture ourselves has emerged as an exhortation to stay healthy during the lockdown. But, significantly, it has also managed to bring the immune system into our living room discussions. Even as we encounter, to our horror, the growing number of deaths across the globe, it is clear that those with a compromised immune system are more vulnerable to the onslaught of the virus.

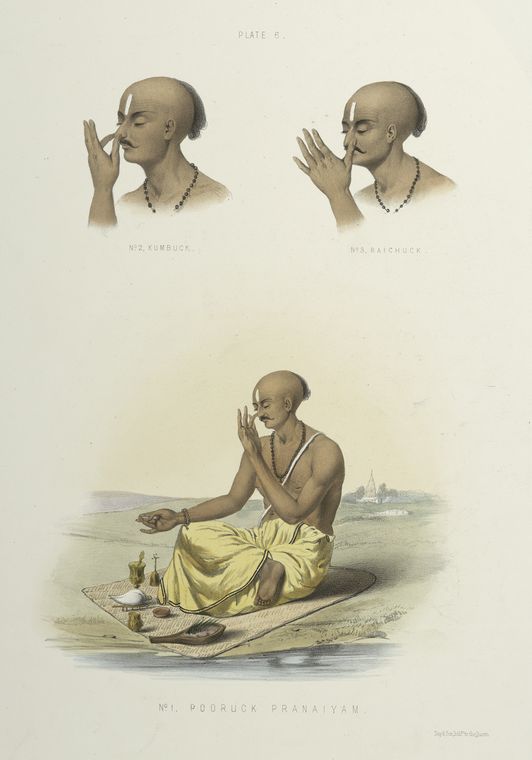

On 20th March 2020, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General of the World Health Organisation, suggested that people could do yoga to maintain their physical and mental health. “This will not only help you in the long-term, it will also help you fight COVID-19 if you get it”, he suggested. How does modern yoga, combining pranayama (breathing techniques) and asana (physical postures), enter the current scene? Can it boost the immune system? And what are the ways in which yoga intersects with spiritual, biomedical and biopolitical approaches to the body, when looked at through the lens of the immune system?

Ghebreysus’ advice resonates with the recommendations made by other health organisations and practitioners. A post on the Harvard Health Blog by John Sharp (M.D), recommends yoga practice to alleviate anxiety in the present circumstances. The impact of stress on the immune system continues to be researched, but some existing studies do suggest a causal connection between higher levels of stress and anxiety and a weaker immune system. While Ghebreyesus’ speech seems to imply a direct connection between yoga and a stronger immune system, Sharp’s post aligns more with the popular association between yoga-meditation and stress-relief. Either way, the intersections of yoga and immunity in present times offer the scope for anthropological inquiry into the entanglements of different understandings of health and the body, and their implications.

Immunity and Lifestyle

Yoga’s emergence as a preventive measure in the current Covid-19 scenario, I believe, is a result of its inclusion in integrative medicine globally, and aggressive push in India through institutional interventions by the state and yoga gurus. Its impact on lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and hypertension seems to be recognised or at least reckoned with by doctors of indigenous medical systems as well as biomedicine. However, lifestyle diseases are non-communicable diseases. The current pandemic, on the other hand, has refocused our attention on the interconnections of the immune system and lifestyle in the context of communicable diseases.

Given the complex networks of cells and molecules that comprise the ambivalent term “immune system”, there are differing and ever-emerging views on the impact of lifestyle on our immunity. A September 2014 post, updated on 6 April 2020, from the Harvard Health Blog states that although at present there are no conclusive studies showing direct links between lifestyle and the immune system, there are nonetheless ongoing research projects investigating their interconnectedness. The post goes on to suggest choosing a healthy lifestyle to keep, “your immune system strong and healthy”. Pathologists and immunologists have also indicated a connection between exercise and diet, and the immune system (Childs, Calder and Miles 2019; Knight 2012).

However, even as scientific research grapples with these interconnections, “boosting”, “supporting” and “strengthening” the immune system through lifestyle practices of diet, exercise and meditation have found renewed salience in the vocabulary of lay people. Talking to my friends and family in India, it seems the immune system has never been as popular a topic for everyday conversations as now. Such narratives combine notions of health and healing with individual agency and empowerment, fixating upon the individual as the nodal point of community-oriented moral responsibility.

Norms of social distancing, wearing masks, washing hands, and self-isolation have placed individual prevention tactics (imposed or voluntary) at the heart of governmental strategies for arresting the virus’ spread. It is in this milieu of emphasis on self-care, fitness, individual agency, and notions of moral responsibility, that many from the Indian middle classes are turning to yoga. As a friend of mine, Neeta (name changed), who recently joined online yoga classes said in a personal conversation, “We can’t do anything except taking precautions and keeping ourselves stress free”.

Such entanglements of notions of stress and immunity, foregrounding individual lifestyle and self-care, are being reconfigured in the present through certain epistemic shifts in the understanding of the body. These shifts combine the yogic with the biomedical, the spiritual with the scientific, and the moral with the political.

Epistemologies of the Body

In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra, arguably the most widely cited yoga text, the asana-pranayama complex corresponds to the body-mind complex. The goal of yoga, Patanjali expounds, is the cessation of all forms of movement that ultimately lead to samadhi (enstasis) (Bryant 2009). While samadhi remains a difficult goal for the householder, in today’s parlance, achieving “consciousness” has emerged as a central aim of yoga practice. In the present context, de-stressing and enhancing consciousness through yoga have combined with discourses of the immune system pointing to intersections of spirituality and science.

An Indian YouTube video from March 2020, with more than 15,000 views, states the importance of yoga asanas and pranayama in preventing contracting the Covid-19 virus by strengthening the immune system. The asanas and pranayama featured in the video are geared toward either or both of two given approaches. One approach is to “give deep relaxation to the whole body-mind complex”, a way to combat the immunosuppressants – stress, fear and anxiety. Echoing such narratives, a yoga-practitioner interlocutor told me, “I find myself driven to practice yoga (in these times). I am practicing more restorative styles as it is comforting and it opens your chest, you feel more air, (it) connects my mind to my body, it feels meditative to pursue it”. The mind-body complex combines here with achieving a spiritual-physical state of consciousness that is further connected with discourses of stress and immunity.

Let me dwell a little longer on the semiotically rich phrase, “opening the chest”. In my yoga classes, teachers would often instruct us to open our chest. Opening the chest is an instruction to achieve the necessary body posture for certain asanas where it refers to, say, holding the torso straight and upright. Or it could be an accompanying motion to stretching the arms sideways. But opening the chest also refers to a condition of psychic, spiritual and physical wellbeing that certain asanas help achieve. Encasing the heart and lungs, the chest signifies a field amenable for combining spiritual and scientific-medical terminologies. The heart, understood in the Upanishads as a void or cavity, is the seat of the atman or the innermost self and of consciousness (White 1996). Opening the chest, then, is opening the “cave of the heart” and thus the soul, to Brahman, the absolute cosmic principle (Kearney 2008).

The concept of the innermost self in the Upanishads is closely connected with the notion of breath or prana (Kearney 2008; White 1996). It is at the juncture of prana/breath that there is perhaps another epistemic shift underway, or has the potential to emerge as such. In the video I mentioned earlier, the second approach involves working on the respiratory system through breathing techniques, “so that the possible attack of the Covid causing respiratory distress can all be avoided”. In the yogic epistemology of the body, breath is a central component. Given that the virus seems to particularly affect the lungs and respiratory system, is there scope for a pranic understanding of the body to become entangled with biomedical notions of the immune system?

Prana, while referring to breath and respiration, is part of a complex system of “vital airs” in the body (Bryant 2009, 571). As the principal life air, prana also directs the other airs related to digestion of nutrients, elimination of bodily waste, circulation in the body, and upward movements (ibid). This complex interconnectedness of breath as operating within a system has the potential to cohere with the notion of the immune system understood as a network complex. But where the latter is understood in biomedicine primarily through the lens of cells, microbes and, increasingly, the gut, yoga in the current situation seems to find an impetus to foreground breath/prana in its understanding of the body and immunity.

Whether there will be longer lasting integration between yoga and biomedicine in the context of the immune system, and in which ways, remains to be seen. Nonetheless, the current pandemic may very well have served to realign yogic and biomedical epistemologies of the body in significant ways.

Immunity, Yoga and the Biopolitical

Let’s return to my friend Neeta who turned to online yoga classes to deal with the anxieties of the pandemic. In the same conversation, she told me that she was particularly anxious about her parents living by themselves in a North Indian city, a few hundred kilometres away from her, in light of rumours about Covid-19 contagion in a local madrasa (Islamic school). These rumours followed the recent associations being made between a rise in the Covid-19 cases in India and an Islamic event organised in New Delhi by the Tablighi Jamaat in March 2020.

As anthropologists have argued, biomedical discourses of the immune system and their mobilisation in national imaginaries are hardly ever innocent. Discourses of immunity inevitably give rise to and reinforce boundary making (Martin 1990). The creation of the healthy s/Self, at the intersections of the individual and national body, involves a process of exclusion and repulsion. What is excluded by the individual body or what should be excluded by the individual body in its quest to become less vulnerable (invincible, perhaps) is at once a question that extends to the national body. As lifestyle practices, including everyday religious practices, of certain communities appear to be particularly suspect, we find ourselves facing questions of, who is seen to make the national body vulnerable? Who is kept out in the creation of the Self? Who can lay claims to individual and collective empathy and care? In these times, intersections of yoga and biomedicine point, again and anew, toward nation building and the biopolitical.

Popularity of the current yoga videos in India and their legitimisation is part of both a longer history of modern postural yoga and recent developments. In his discussion of modern yoga in India, Joseph Alter writes, “Yoga’s position within the discourse of nationalism made it possible to imagine – in terms of the body and embodied practice – a global community” (2004, 102). Yoga universalises, simultaneously, an embodied practice and Hinduism, by way of individual lifestyle and establishing connections between the present and a glorious Vedic Indian past. The government’s active support to yoga coupled with the immense popularity of contemporary charismatic gurus, boosted through television and the social media, has consolidated yoga as India’s unique gift to the world while also mobilising national pride in India’s “traditions”. Such traditions are extolled in narratives both nationalist and universalist insofar as these are taken to be exemplary of ancient Indian wisdom that is at the heart of Hinduism and yet true for all mankind.

These entanglements are, of course, far from straightforward. But the power of these entanglements lies in their ability to subtly penetrate everyday lifestyle practices around health and fitness. In one of my yoga classes (much before the lockdown), the instructor urged us to stay away from alcohol at least for the duration of the course. We should treat this period as “detox” time, she said. The language of rectifying the malaise of over-consumption easily integrates with rules of purity and pollution around caste and religious differences. In a different class with a different instructor, a non-practising Muslim classmate confided once in private that she was worried the instructor would smell her post-lunch garlicky breath! “They don’t like it”, she said, referring to the Hindu dietary conception of onions and garlic as “hot” food that can give rise to “impure” thoughts. In a country where charismatic religious and political leaders carry much clout, their voice makes it difficult to divorce “self-transformative” practices from the wider context of growing Hindutva leanings and the latter’s “soft” insertions into the everyday. At the same time, consumption of these practices insulate one from larger socio-political issues.

Focus on the individual body allows practitioners precisely to decouple the physical body from its socio-political constitution. Keeping oneself stress-free in these times is important. But does emphasis on the individual body make one immune to the exclusionary politics of these practices?

The unprecedented challenge of the times has thrust new reckonings upon us, compellingly so in matters of health and healing. Religio-spiritual practices inevitably gain new grounds in times of crises. This is especially the case now in case of physical-spiritual practices of the body. Yet, this is also the time to interrogate transnational understandings of the body and immunity to notice subtle shifts within epistemic frames formed through the intersections of the spiritual and the physical. And the implications of the imaginaries of the individual and national body, at once spiritual and scientific, for a collective ethics of inhabiting these fraught times.

Bionote

Tuhina Ganguly is Assistant Professor at the Department of Sociology, Shiv Nadar University, India. Her primary research interests are in the area of contemporary religiosities and spirituality. Tuhina’s current ethnographic project is focused on the intersections of spiritual practices and epistemologies of the body.

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.

Works cited

Alter, Joseph. 2004. Yoga in Modern India: The Body between Science and Philosophy. Princeton University Press: Princeton.

Bryant, Edwin. 2009. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali: A New Edition, Translation and Commentary with Insights from the Traditional Commentators. North Point Press: New York.

Childs, Caroline E., Philip C. Calder and Elizabeth A. Miles. 2019. “Diet and Immune Function”. Nutrients 11(8), 1933. DOI-weblink.

Kearney, Richard. 2008. “Pranayama: Breathing from the Heart”. Religion and the Arts 12: 266-276.

Knight, Joseph A. 2012. “Physical Inactivity: Associated Diseases and Disorders”. Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science 42 (3):320-337. Weblink.

Martin, Emily. 1990. “Toward an Anthropology of Immunology: The Body as Nation State”. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 4(4): 410-426.

Sharp, John. “Coping with Coronavirus Anxiety”. Harvard Health Blog. March 12, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2020. Weblink.

White, David Gordon. 1996. The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago.