Pippi Kragtwijk & Margreet van Es

This week will mark the start of the month of Ramadan in 2021. For many Muslims, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar is not only about strengthening their relationship with God, but also with their families, friends and neighbors. However, in the Netherlands, as in most places in the world, the Corona crisis will strongly limit the opportunities for Muslims to give shape to the Ramadan in their most preferred way. In this blog, we look back at the Ramadan in 2020, which coincided with the first ‘intelligent lockdown’ in the Netherlands. How have Dutch Muslims experienced the Ramadan last year? And what does this tell us about how religion transforms during a pandemic?

During the month of March 2020, the Dutch authorities announced more and more measures to limit the spread of the Coronavirus. People were asked, among other things, to stay inside and work from home as much as possible, limit their social contacts ‘on location’ to a fixed number of people, and keep 1,5 meters distance at all times from people who do not belong to the same household. Events were cancelled, and many public facilities and ‘non-essential’ shops were closed. On 23 March, PM Mark Rutte spoke of an ‘intelligent lockdown’. It was meant to last for a few weeks only, but it became extended several times until some of the restrictions were gradually lifted from May onwards.

Religious gatherings in houses of worship were not forbidden, as the authorities deemed such measures unconstitutional. Nevertheless, a voluntary agreement was made on 26 March between the authorities and many faith organizations in the Netherlands, including mosque associations. Religious services were to be provided online as much as possible. Religious gatherings on location – if held at all – were limited to a maximum of 30 people at a time, and these people had to wear face masks and keep 1,5 meters distance from each other.

These rules also applied during the Ramadan, which lasted from 23 April until 23 May.[i] For most Dutch Muslims, this implied that they could neither visit the mosque for iftar or prayers, nor break their fast at home with their friends or relatives. Long-anticipated events such as cultural festivals, fundraisers and interfaith dialogue iftars were canceled. PM Mark Rutte and other government officials explicitly asked Muslims to break their fast at home with their own family, and to avoid visiting other people.

In an attempt to find out how Muslims experienced the Ramadan in 2020 compared to previous years, Pippi Kragtwijk conducted semi-structured, in-depth interviews with seven Muslims living in the Netherlands, who formed a heterogeneous group in terms of age, nationality, place of residence, and education level.[ii] How did the lockdown affect their ritual and social practices during the Ramadan? How did they adapt to the new situation? And how did they experience the month of Ramadan emotionally and spiritually in comparison with previous years?

When asked about how they spent the month of Ramadan in previous years, all seven respondents indicated that they see the Ramadan as a time for contemplation. They try to de-prioritize their regular activities, slow down their hasty lives, and give themselves a ‘spiritual boost’, as one of the respondents called it.[iii] Many of them engage in additional acts of worship that go beyond the five daily prayers, such as reciting verses from the Qur’an, making supplications, or spending many hours in the mosque to say the night prayers together with other Muslims. At the same time, the respondents indicate that the Ramadan normally includes a wide range of social activities that keep them busy in the evenings: organizing large family dinners at home, visiting friends or relatives for iftar, or having a chat with people in the mosque in between prayers. For the respondents, the Ramadan used to be an opportunity to reconnect with people they had not met over a long time.

These social activities, and also the opportunity to go to the mosque on a regular basis, were deeply missed in the year 2020 – by men and by women. A male respondent explained how the whole structure of the Ramadan fell apart:

Normally you have a daily rhythm. You fast during the day, and after breaking the fast you go to the mosque. You meet people, you pray together, you have a chat with someone. When you don’t have that anymore, you really miss it. You take it for granted, and all of a sudden it is taken away from you.

A young female respondent expressed her sense of loss when she could no longer say the night prayers in the mosque:

You just miss the whole atmosphere: the people, the sense of togetherness. When the imam leads the congregational prayers, it feels totally different than when you say the same prayers on your own. […] In the mosque it feels more powerful. […] You have this moment when everybody says ameen – it is so beautiful! It gives me goose bumps. That feeling when people become a unity before God – I didn’t experience it the same way this time.

In fact, several respondents remarked that praying at home did not feel as powerful as praying in the mosque. This shows how the material, embodied experience of saying congregational prayers in a mosque can create a ‘wow effect’ (Meyer 2016) that cannot simply be recreated at home.

In an attempt to offer online alternatives, several mosques organized live-streams of congregational prayers (performed by a small group of people on location), online fundraisers, lectures about Islam, or Ramadan talk shows. These online sessions were quite popular among the respondents, but they were at most experienced as an inferior substitute for the ‘real thing’.

Furthermore, many respondents lamented that they could not have big family iftars at home. These gatherings were not only important for their emotional well-being, but also gave them a sense of spiritual fulfillment. One woman said:

It was the first Ramadan where we did not have the whole family over for dinner. This is a very big and important thing. My husband and I, everyone said the same: this does not feel like Ramadan. We are not happy when we eat alone.

Whereas Dutch newspapers reported about Muslims families having iftar together via Zoom or Google Hangouts, the respondents seldom heard about any online iftars in their own social environment, and they did not participate in any such event either. A young woman said:

I thought we could organize something for Eid-ul-Fitr via Skype, but no-one in the family was interested. They were not really used to these technologies either.

A male respondent said:

What are you actually supposed to do then? Showing people that you are eating soup? It just doesn’t work.

Social contacts remained mostly limited to WhatsApp messages, phone calls, and outdoor meetings with people living nearby. Some respondents admitted that they had broken the corona rules to spend time with their family on Eid-ul-Fitr. Otherwise, they said, the day would become too heavy and too lonely, and they would miss their family too much. This illustrates the importance of the social dimension of the tradition.

Meanwhile, the respondents tried to focus more on individual acts of worship that they could perform at home: reciting verses from the Qur’an, reflecting on these verses and on themselves, performing extra supplications, or trying to have a better concentration in the five daily prayers. Newspaper articles suggested that due to the lack of social activities, Muslims had more time for individual contemplation. For some of the respondents, this worked out well. A young male respondent and his wife decided to spend the nights reading the Qur’an together, with the husband explaining verses to his non-Arabic speaking wife. For them, the lockdown provided an opportunity to share spirituality in the intimate atmosphere of their home. In such cases, the impoverished social dimension gave way to a more individualized cultivation of piety.

However, several respondents ultimately became disappointed in themselves, because they did not manage to spend as much time on acts of worship as they had wanted to. This especially applied to those who had lost their job as a result of the Corona crisis. They felt guilty about ‘wasting’ the extra time that had become available to them, and they doubted whether they had invested enough in their relationship with God. One woman said:

At some point I became stressed. What kind of extra worship did I actually do? How strong is my bond with God? [….] Had I done more if I were in the mosque? […] I started to doubt myself, like: you love God, you are doing a lot for God, but is this everything you managed to get out of it? Even now that you are at home all the time?

It seems that they set very high goals for themselves that turned out to be impossible to achieve on their own – especially without the supporting environment of a mosque building that induces religious sensibilities as soon as people come in, the opportunity to say congregational prayers, and face-to-face encounters with people who observe the Ramadan in more or less the same way.

These experiences show how the material, social, and spiritual dimensions of religion are interconnected. The enforced ‘sobering’ of the Ramadan was overall perceived as a frustrating experience that lowered the respondents’ spiritual satisfaction. A young woman said: ‘We fasted, but it did not feel like Ramadan at all.’ Others expressed a sense of acceptance and hope for the future. A woman said:

It was really a pity that we couldn’t receive many people. But you have to make do with what you have. We just have to follow the rules, and if this is what helps … Hopefully we will see better times soon. We also just pray for that: that this situation will soon be over, that better times are coming, and that everyone stays healthy.

All respondents expressed their hope that the month of Ramadan in 2021 would become ‘normal’ again. At present, it is clear that this will not be the case. With the vast majority of the Dutch population still waiting to be vaccinated, and with the third wave of Corona infections fully going on, the current lockdown will again restrict Muslims’ activities during the month of Ramadan.

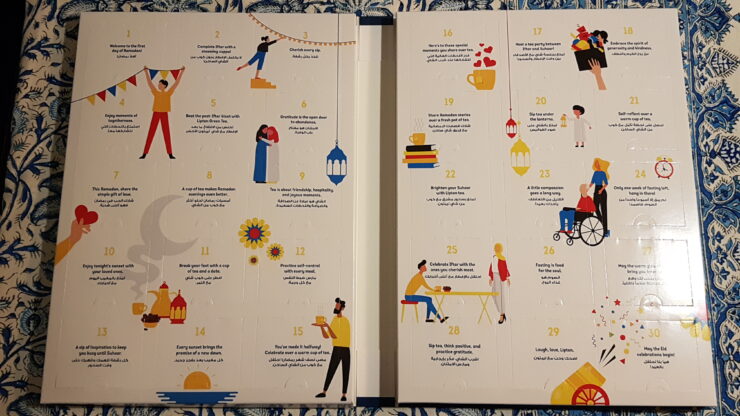

Meanwhile, a famous tea brand has developed a Ramadan calendar for this year. Modelled after the Christian advent calendar, it has exactly 30 compartments – each little door hiding two tea bags. Ramadan calendars are not a new phenomenon: Muslim parents have been making or buying them for their children for several decades. They often contain chocolates or small gifts. This one, however, is made for adults. And although it is decorated with drawings of small groups of people who are having a nice cup of tea together, the product (two one-cup sachets per evening) is clearly not made for large social gatherings. This new Ramadan calendar is perhaps the commercial epitome of what can be called the individualization of the Ramadan as a result of the pandemic. After having iftar at home – with their close family, or perhaps all alone – Muslims can open a new compartment of their calendar, sit back with a warm cup of tea, and have a moment of contemplation. As such, the calendar offers Muslims a new Ramadan ritual – even though it is not what they had hoped for this year.

This blog was co-written by Pippi Kragtwijk [iv] and Margreet van Es, based on Kragtwijk’s Master thesis ‘Ramadan in 2020’. Her thesis was supervised by Margreet van Es.

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.

References

[i] The start and end of the month of Ramadan are determined by (competing methods of) moon-sighting, which means that different Muslim minority groups in the Netherlands may start or end the Ramadan on different days.

[ii] The interviews were held during the Autumn of 2020. The number of respondents is low, and the respondents should not be seen as representative for all Dutch Muslims. Nevertheless, the in-depth interviews give a good indication of the adaptations made by some Muslims, and their subjective experiences.

[iii] For an-depth analysis of the efforts taken by Muslims and Christians to ‘make time for God’ in a fast-pace secular society, see Beekers 2021.

[iv] Pippi Kragtwijk obtained her Master’s degree in ‘Religion and Society’ from Utrecht University in January 2021. For her final thesis, she studied the effects of the Corona lockdown measures on the Ramadan experience of Dutch Muslims in 2020. She currently works as a copywriter and content specialist at a content agency.

Thumbnail image via Pexels