Annewieke Vroom

When my research into Buddha statues in Dutch living rooms stagnated due to the lockdown,[1] I researched ten Zen Buddhist communities in the low countries looking at online Zen Buddhism. My main question was whether there would be a special re-invention of the Zen Buddhist tradition in the context of the pandemic, either because of the crisis itself or because of the transition to online religion. The experiences differed from case to case. In this blog, I give some impressions of five Zen Buddhist communities with regard to new rituals.

Impressions

The first Zen group to close down -even before the lockdown- was the He Hua (Lotus)Temple in the Amsterdam red light district. This monastery run by nuns is not secluded, on the contrary: it is part of a network of a Taiwanese mission with around 300 temples spreading ‘humanistic Buddhism’ worldwide, the Fo Guang Shan (Buddha’s Light Mountain) Monastery. For Miao Yi, head abbes of the temples in Amsterdam and Antwerp, going online was pivotal to continue to serve the local community. She also set up a network with the fourteen European temples, dividing courses and opening up services. Going online was painful, for example when a funeral rite had to be performed through digital distance. But it also had an unexpected positive result. Miao Yi: “Thanks to the corona virus our older members and volunteers had the courage and motivation to learn to work with the internet. They needed their grandchildren to help, which brought closer connections in their family. Earlier, they preferred to go shopping or sports, but now they helped the older generation, learning Buddhism together.” To compensate for the cancelled Buddha’s Birthday Celebrations a minigame was created. Millions of members worldwide washed the toddler Buddha by clicking on a picture of a wooden spoon, after which wise quotes popped up and and rays of light enveloped Buddha. Indeed, the game proves irresistible (I think) (try, or see Fig.1).

Floor Rikken, who is part of zen.nl, the largest nationwide network of Zen teachers [website] moved her courses online right at the start of the lockdown. This was a collaborative operation for the network, and they filled their common website with pictures of many teachers working online (See Fig. 2). To her surprise, people wanted to keep the tea ceremony, even those who normally seemed not so keen: “Now we drink our own tea in silence and share the ritual by showing our cups one by one.” A new tradition also emerged: “The moment of exit was felt to be too abrupt. Now, I say goodbye to the students one by one by calling out their names before they log off”. The only thing that’s exactly the same is the sitting meditation. Does that work? Rikken: “Yes, it does. There is a bit more movement, a phone that is picked up or something, but that’s ok, I don’t pay attention to it.”

Zen teacher Misha Beliën, for whom going online was “fun and interesting,” also reports new rituals taking place. Working online gave him the opportunity to experiment with his weekly evening meditations sessions for Zen Centrum Nijmegen. “It’s nice to be creative in a new way. One time we did a ritual with ‘old karma’ which everyone wrote down on paper. I walked outside and burnt it in the garden, while my girlfriend filmed this from the window.” Because of both the communications necessary to set up the new ways of workings, the group teachers and volunteers became more intensely related. Also, the nature of their relations changed. Beliën: “It is also becoming more intimate or homely somewhere. By practicing from the living rooms we are all together a bit more in each other’s private atmosphere. For some participants, there was more reason to share private things, because there is a loss in their environment. That also adds to the intimacy.”

Michel Oltheten, who has a growing Zen community called Zen Heart in his own house in Den Haag, also quite promptly moved all his activities online, with the motto “to distance, but to not isolate.” He reports that it is not so much rituals, but rather “the ‘pastoral aspect’” of his role that came to the fore. On his website, he started a small “Love in times of Corona” forum for members to help each other in case of need (see Fig. 3). He saw online practices were very popular, especially when the lockdown was strict. His weekly dharma lectures now had a show-up of over 40 participants, instead of just the normal average of 12. Participants ranged from long term Zen Buddhist practitioners to beginners. Oltheten: “It’s not that I am so much more well-versed now. People need it more. And they seek to belong somewhere.” Very popular also were his weekly online “listening circles,” where people share their concerns through heartful speaking and listening. It was a common practice, but now more focused on the common situation. Even the new people freely shared their pandemic-sorrows, and also, joys.

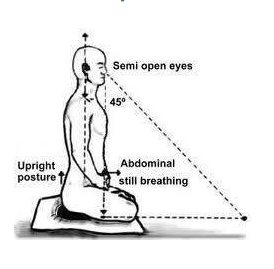

Also, as could be expected, Zen Buddhism lends itself for an individual approach. City monk Paul Loomans, famous in the Netherlands for his book and courses on Tijdsurfen (Time Surfing) invented his own lockdown-amendment. In lieu of co-practitioners to check on his meditation posture, he made use of the occasion to take a serious look at it himself by doing his Zen in from of a mirror. Loomans, member of the Gyo Kai Zen Center in Amsterdam, explains: “In the tradition of Zen master Deshimaru, the posture is the alpha and the omega of meditation. It was very valuable for me, to correct meditation patterns that crept in over the years. For example, I sat a little too much forward, and my thumbs were a bit too relaxed. This has an effect, as the body posture is one with the mental posture.” (see Fig. 4, a picture for the perfect posture). Loomans stresses that for him, there is no special corona-variety of Zen Buddhism: “Meditation is a spiritual practice in which you let go of yourself and let your thoughts pass. The North Pole of the practice is to sit without purpose and not for any kind of benefit.” Later in the lockdown, Loomans thoroughly enjoyed the online “za-zoom” with his Zen master in France, who he usually sees only once a year, and found it very special to be more in touch with for example the French and Spanish communities.

Reflections: new rituals?

This is just an impression of the wide range of responses I found when researching ten Zen Buddhist communities in the low countries. Strikingly, the communities varied greatly in their responses to online working, depending on the specific kinds of Zen Buddhism they practice. The ways the different groups went about their online practice reveals a bit about their unique characteristics, as the following brief comparison will highlight.

For Floor Rikken from zen.nl-Utrecht, the adaptations were rather pragmatic so as to optimise practice. To her surprise attention to the ritual dimension (tea ceremony, exit-ritual), normally also frowned upon by some -she is part of a down-to-earth branch of Zen- was explicitly asked for. For Misha Beliën at the Zen Centrum Nijmegen, going online was a welcome opportunity for experiment. Indeed, he tried out new rituals, actually performing them online. Simultaneously, what moved him more was the increased intimacy due to the shared crisis. This increased intimacy is also found at Michel Oltheten’s community in Den Haag, where practice became more strongly centered around intimate sharing and belonging when going online. Loomans from Gyo Kai Amsterdam made a typical “Desimaru Zen” move during the pandemic, focusing on his posture. Even so, what he most deeply appreciated was the opportunity to connect online to his own and other teachers in the broader European network. This appreciation of the increased international work was also found at the Taiwanese monastery at the Amsterdam city center, where a great increase in pan-European and worldwide cooperation could be found- with as most entertaining highlight the mini-game with toddler-Buddha – while also local solidarity was also kept up though online work.

Concluding, while the pandemic and the lockdown were taken up in different ways, they generally had three effects on Zen Buddhist groups in the Netherlands: an increase in intimacy and solidarity; a delocalisation and strengthening of the international network; and the rise of new or adapted online rituals.

Want to know more about how Zen Buddhists went about adapting their teachings during the pandemic and lockdown? Read more in Part II (published July 5th, 2020) or Part III (published July 8th, 2020).

This blog is a part of ‘Dossier Corona’, introduced by Religious Matters in the spring of 2020.

[1] My research, financed by the Department for Philosophy and Religion (UU), on the workings, meanings and use of Buddha statues in Dutch homes seeks to contribute to a deeper understanding of the plurality of contemporary (post)religious and (post)secular life that also stands central in the Religious Matters programma. Approximately one on three households has either a Buddha or a Chinese luckgod, also identified intuitively as a Buddha. Visiting these statues and their owners, I want to find out if and how the statues are (re)acted upon and thought about within and beyond their decorative function.