Annelise Reid, PhD candidate in the research project Religious Matters, has been awarded the Speckmann Prize 2017 for her MA thesis ‘Moved by the Spirit: Sensing the Divine in a Pentecostal Church’. This prize is awarded annually by the Leiden Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology for the best MA thesis. Congratulations Annelise! Want to know more about her research? Read her contribution to the Leiden Anthropology Blog.

God is disappearing from the Netherlands, according to a 2016 survey. But this is misleading. New religious movements such as Pentecostalism are growing worldwide. For my MA, I made a film about 3 months’ fieldwork in a Dutch Pentecostal community.

New religious movements

The sweeping generalization that God is disappearing from the Netherlands seems to affirm the idea that modern secular nations like the Netherlands are finally being freed from the traditional and irrational bonds of religion. But it is misleading to think that religion is on the way out. In our increasingly pluralized societies, religion is still, and in new ways, a key issue in defining identity and belonging.

New religious movements such as Pentecostalism are growing rapidly worldwide and have become powerful vehicles of spiritual and socio-political change. So to me this suggests that religion is not disappearing, but rather being transformed in new and unexpected ways. For my research, I engaged with this fascinating paradox by researching congregants’ experiences of the manifestations of the Holy Spirit.

Shifting the Gaze

To date, most anthropological research on Pentecostalism has tended to focus on the African and South American contexts – which in my view tends to unconsciously reproduce the teleological idea that those people in those places are more prone to being religious (i.e., more traditional, irrational, and less cultivated).

With my research, I wanted to focus on the Dutch context and asked what Pentecostalism looked like in a ‘modern’ secular country like the Netherlands which claims ‘God is disappearing’. In shifting my analytical gaze to ‘home’, I hoped to disturb the west-rest, modern-traditional, secular-religious binaries that inform so much of our thinking about what it means to be ‘modern’, as well as how we see and value religion today.

Sensing the Divine

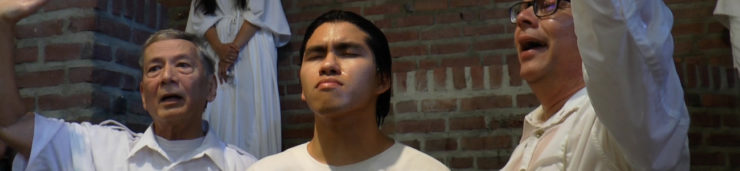

Spending three months immersed in a Pentecostal community revealed to me that the power and authority of Pentecostalism lies in the way congregants are moved. I mean moved here in both senses of the word, involving both emotional and physical dimensions.

It is within a concrete repertoire of bodily-emotional sensations that the Holy Spirit becomes present to congregants.

Combinations of tears, warmth, sweat, goose bumps, tingling, stomach pressure, laughter, joy, sadness, dancing, falling, and rocking all become tangible manifestations of Divine presence. These emotional-corporeal repertoires function as the empirical space within which belief is generated and sustained among congregants.

My immersion into the dense and intense ritual life of the community further revealed to me how these ecstatic experiences of the Divine form part of an emotional economy which facilitates the conversion of moving experiences into spiritual capital. This conversion of experiences allows congregants who are otherwise on the margins of society for various reasons to assume a central role within the community.

Communities of born-again brothers and sisters are forged and negotiated along sensuous lines, and experiences of the manifestations of the Holy Spirit hold the revolutionary capacity to cut through differences in gender, culture, education, class, and age. My thesis is interwoven with personal reflections on my own moving encounters and how they became valuable vehicles in my own attempts to reach out to and understand the ‘other’, as well as negotiate my place within the community.

Tangible belief

Congregants’ experiences of the Holy Spirit offer a direct critique on what it means to believe. The study of religion has historically been plagued by an intellectualist notion of belief – viewing belief as a set of illusionary ideas about the world that have no empirical grounding. However, by focusing on congregants’ experiences, I was able to show that belief is very much something congregants do rather than just think.

For congregants, belief was as much a response to particular embodied experiences as it was a reflection on them. If I had focused only on the discursive aspects of congregants’ experiences, I would have missed the ways in which congregants’ bodies and senses led them to a certain knowledge of the world and engagement with self, God, and community.

Ethnographic encounters

The emphasis on sensing is present in my research on different levels and in various forms. Theoretically, it offers a space to think about belief as an empirical phenomenon that consequently challenges Modernity’s teleological understanding of religion as more backward, irrational, and traditional.

Sensing also refers to acknowledging an asymmetrical relationship within anthropology between text and language on the one hand, and the body, senses, image, and sound on the other hand. I wanted to challenge this text-centred understanding of the ‘other’ and see what kind of knowledge could arise if I brought sound and image into the equation.

For me, this meant reaching out to and engaging with the community in ways that did justice to their experiences. This demanded a certain level of methodological creativity on my part. Reflexively using my own body and senses as a research instrument and employing audio-visual methods was a way for me to engage more directly with congregants’ experiences.

Film became an important medium for translating experiences in ways that did not reduce them to mere text. I did conduct interviews, but I also participated in rituals, attended conferences and evangelical protests, became fill-in church musician, pastor’s assistant, cook, and babysitter, spent hours chatting over coffee and dinner, and spent a large part of the last month filming and recording life in the community. I feel that the kind of research I did could only be achieved with time and living with the community. That’s the beauty and value of doing ethnographical fieldwork!

Acknowledgements

I am greatly indebted to Pentecostal community ‘De Open Deur’ for their openness in letting me be a part of their lives for three months. Many thanks go my supervisor Erik de Maaker who allowed me to bite off more than I could chew with this research and faced the challenge with me. My research is the result of many inspiring conversations with you and a response to all your critical red lines throughout my drafts. Thank you!

On 6th March, Annelise Reid was awarded the Speckmann Prize 2017 for her MA thesis ‘Moved by the Spirit: Sensing the Divine in a Pentecostal Church’. The MA Speckmann prize is awarded annually by the Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology for the best MA thesis.

This blog post appeared earlier at Leiden Anthroplogy Blog